Concept 35: Federal Deficits, Surpluses, and Debt

Overview: You hear the words deficit and debt all the time. What's the difference and is one more important than the other? Click here to find out.

Learn

Beginner

Note: We strongly recommend completing Concept 34 – Fiscal Policy before this concept.

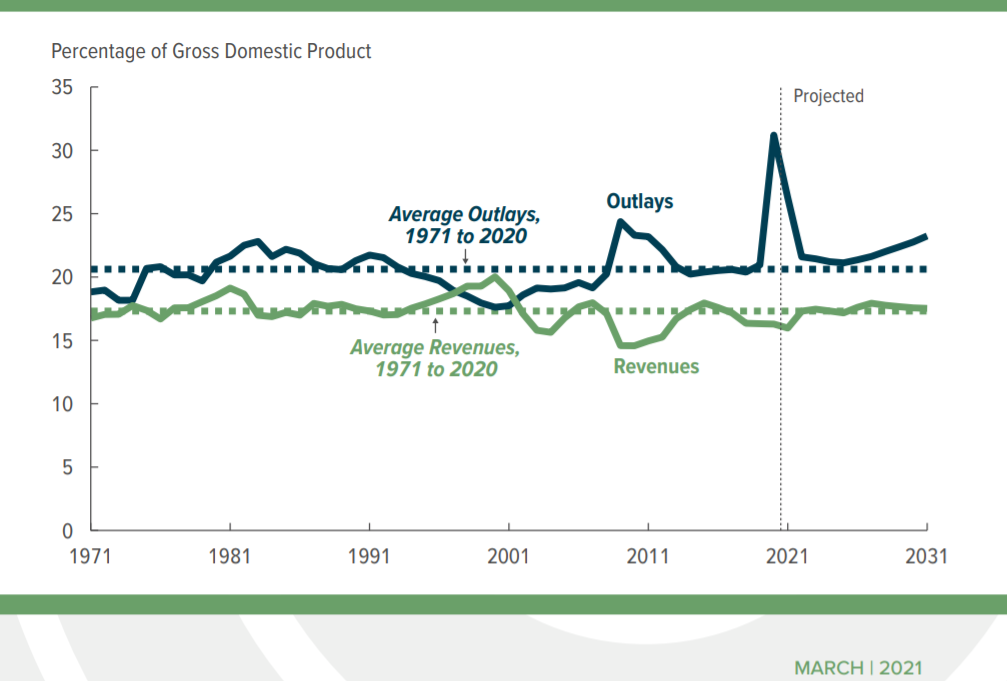

Each year the U.S. federal government passes a budget that explains how it plans to spend its tax revenue. In theory, the budget process can have three different outcomes: it can be balanced, in a surplus or, most commonly, in a deficit.

A balanced budget means that the amount of revenues collected equals the number of dollars spent. Because tax revenues are projected (based on expected national income) and not known for each year, achieving a balanced budget is nearly impossible for the federal government.

A budget surplus occurs when tax revenues are greater than federal spending for the year. This has only happened a few times in U.S. history and not since 2000.

A budget deficit occurs when tax revenues are less than federal spending. This is the most common outcome in the U.S. Having a budget deficit, of course, means the federal government must borrow money to make up the difference – just as a household would have to do if they spent more than they earned in income.

An accumulation of deficits over time adds to the federal debt, which is the total amount of money owed by the federal government.

Knowing the difference between deficits and debt is important to understanding fiscal policies. Deficits are short term; debt is long term.

Intermediate

You may be wondering how budget deficits occur. After all, how can the government spend more than it receives? In short, by borrowing.

Assume the government takes in $100 in tax revenue and spends $150 in a given year. This means it has a $50 budget deficit for that year. Since raising taxes takes time and is unpopular, the government is unlikely to raise taxes immediately to make up the difference. Instead, it announces to the public that it will sell a treasury bond for $50. Whoever owns this bond will receive interest payments, and the government promises to repay the $50 in the future. Someone with $50 in the bank buys the bond (gives the $50 to the government) and -- just like that -- the $50 budget deficit is covered.

Of course, the government now has a $50 debt as it must repay that $50 plus interest at some point in the future. The theory is that at some point in the future, tax revenues will be higher than spending (creating a surplus), and the government will be able to use that surplus to pay off the debt. Historically, this has not worked out.

In the U.S. there has been a long-running tendency to increase government spending on services and decrease taxes. This has led to decades of what is known as deficit-spending that continually increases the U.S. debt. Even when surpluses were run in the late 1990s/early 2000s not all of that was used to pay off debt. Some wonder how long this trend can continue. The short and over-simplified answer is “as long as there are people who want to buy treasury bonds.”

To see current deficit and debt numbers, visit usdebtclock.org.

Advanced

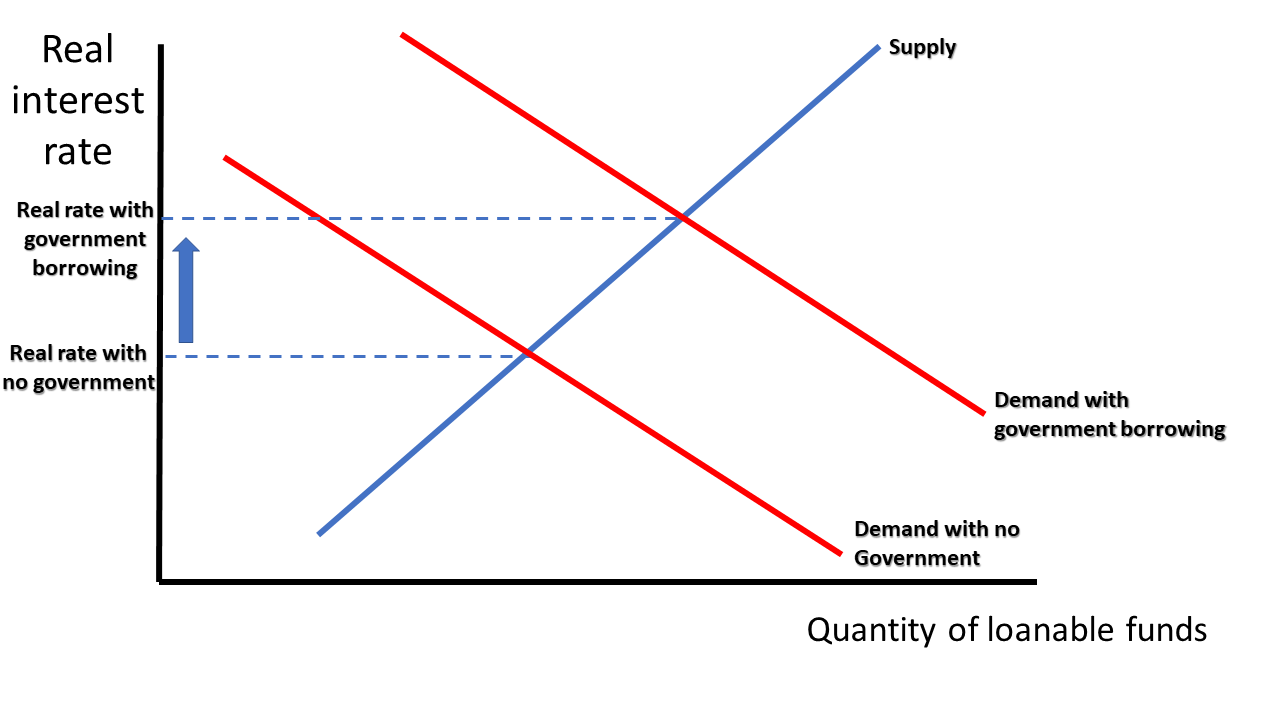

In the example used in the intermediate reading, we stated that someone with $50 in the bank used that $50 to purchase the treasury bond. If we assume that $50 was held in a savings account at a bank, the bank now has $50 less to lend. This is a simplistic example of potential problem with extensive government deficits called crowding out. If the government continues to offer more and more treasury bonds, eventually buyers will pull money out of private savings to get these bonds. With this decrease in the supply of savings (or loanable funds in the bank) the real interest rate in the economy is likely to increase over time. Higher interest rates would lead to fewer business investments and large consumer purchases like cars and houses. Therefore, any GDP gains from the deficit spending by the government may be “crowded out” by decreases in investment and consumption. In practice this effect can be offset by expanding the money supply (through monetary policy), which requires significant coordination, timing and successful implementation.

Click a reading level below or scroll down to practice this concept.

Practice

Assess

Below are five questions about this concept. Choose the one best answer for each question and be sure to read the feedback given. Click “next question” to move on when ready.

Social Studies 2024

Explain how government budget deficits or surpluses impact national debt.