Caption

A bill to allow naloxone nasal spray in public schools passed the Georgia state Senate Feb. 29, 2024.

Credit: Ellen Eldridge / GPB News

LISTEN: A bill to allow opioid overdose reversal medication in schools passed the Georgia Senate Feb. 29, 2024. The bill passed unanimously and now heads to the House. GPB’s Ellen Eldridge has more.

A bill to allow naloxone nasal spray in public schools passed the Georgia state Senate Feb. 29, 2024.

Senate Bill 395 allows teachers, administrators, visitors, and anyone in a public-school building to carry naloxone, known by its brand name Narcan.

Currently, only a school nurse can stock or administer the nasal spray medication, which is designed to stop an opioid overdose.

Overdose can happen after ingesting a single pill as easily as taking too much opioid medication via injection.

Bill sponsor Sen. Clint Dixon, who lost a family member to an overdose, said even bystanders can feel comfortable aiding in a suspected overdose situation — like at school.

"There's no known side effects to the drug," he said. "Also, if it's administered and you're not having an overdose from fentanyl, there's no known side effects from it."

Naloxone, which is an opioid antagonist, binds to opioid receptors and blocks physical effects such as respiratory depression that can lead to death.

The bill strongly encourages schools to stock naloxone but they won't be penalized for not having Narcan on hand.

Dixon said grants are available to help schools pay for naloxone nasal spray.

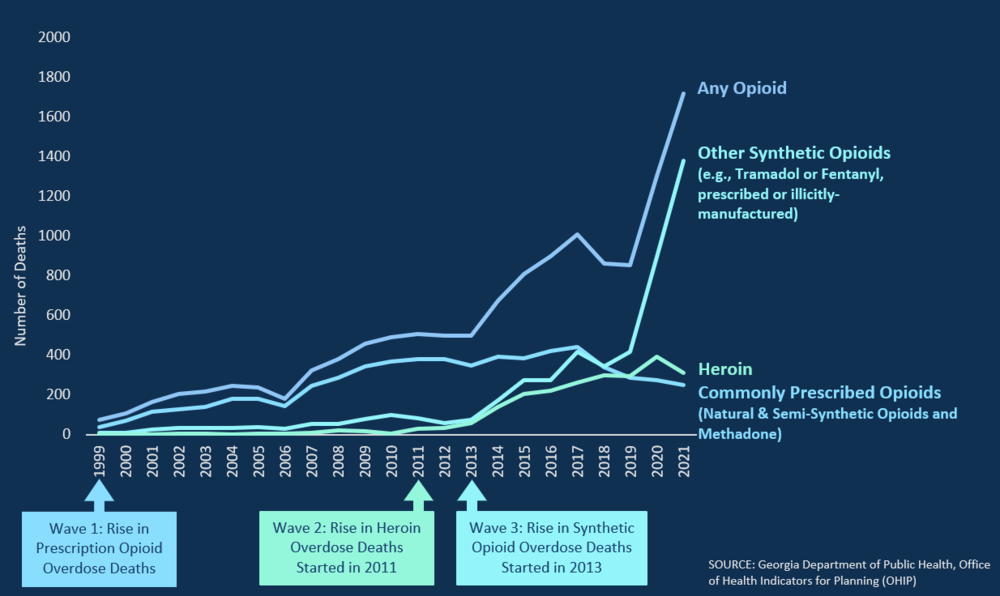

The Federal Drug Administration approved the first over-the-counter naloxone nasal spray in March 2023 to help reduce drug overdose deaths, which continue to climb due to stronger synthetic opioids like fentanyl.

Naloxone is not a controlled substance, and anyone with or without medical training can spray the medication in a victim's nose.

Lawmakers already passed a bipartisan bill this session allowing naloxone in vending machines.

House Bill 1035 sponsor Rep. Sharon Cooper said Georgians could soon find vending machines on all college campuses.

So far, there’s one at Emory University’s Addiction Center. Sydney Wilkins, who represented the center at a hearing for the bill, said the university aims to expand its Narcan vending machine program across all of its three campuses, but that’s impossible to do unless permissions to fill the machines are expanded.

RELATED: Stronger opioid overdose reversal medicines worsen patients' withdrawal symptoms

Additionally, lawmakers now have five places in the Gold Dome where emergency supplies include opioid overdose reversal kits.

In January, Emergent BioSolutions extended the shelf-life of newly manufactured Narcan Nasal Spray products from three to four years, but a study published in 2019 in the journal Prehospital Emergency Care showed naloxone products designed for injection met the standards for safety and efficacy 30 years after expiration.

Narcan is just one of the tools in the fight against opioid use disorder. Syringe exchange programs are another.

In 1994, researchers at Emory University saw rising rates of HIV and hepatitis C infections in the Atlanta area.

Some concerned citizens, one of whom was Mona Bennett, connected the rise in infectious disease to an area known as “The BLUFF,” which is made up of multiple neighborhoods around English Avenue and Vine City where illegal injection drug use and dealing occurred.

Syringe exchange programs were in a legal gray area back then, but Bennett formed the Atlanta Harm Reduction Coalition as a nonprofit dedicated to helping vulnerable people with substance use disorders.

Without regulations around syringe services programs, people shared needles, AHRC Executive Director Dr. Mojgan Zare said.

“They're either sharing them among each other or they're just reusing the needles,” Zare said. “They don't have the protective equipment to protect themselves.”

That changed in 2019 when Gov. Brian Kemp signed a law allowing the Georgia Department of Public Health to regulate these services.

Those strict regulations weren’t published until August 2020, Zare said, and AHRC didn’t have any funding associated with the law, so ramping up services was slow going. This was especially true during the first year of the coronavirus pandemic.

Nina Downs and Bethany Crippen at the AHRC Lyla Center in Woodstock, Georgia.

In May 2023, AHRC opened the Lyla Center in an unassuming office complex not far from Interstate 575 in Woodstock.

The clinic provides clean syringes to people who inject drugs in Cherokee and other nearby counties.

"The point is to provide them clean using materials like sterile syringes, cookers or things like that to prevent infectious disease," said Bethany Crippen, who works in the office.

Additional harm reduction tools like fentanyl and xylazine test strips, and condoms for safer sex are also available free of charge along with medication assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid and alcohol use disorders.

Crippen said they offer resources for clothing, food pantries, and job preparation programs.

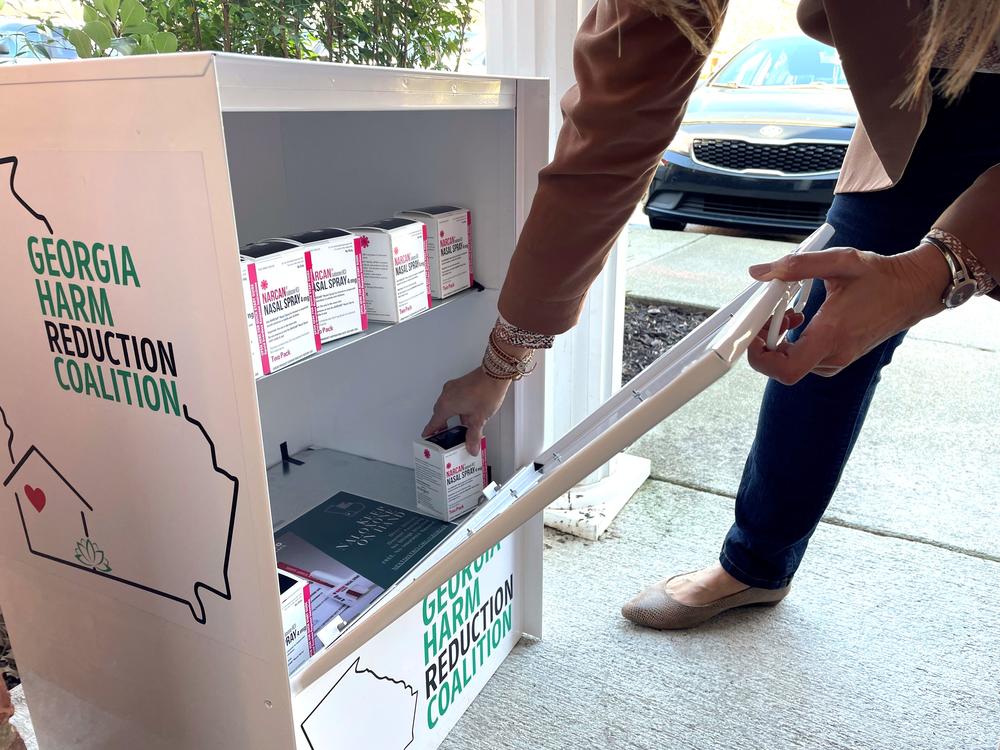

The Lyla Center is a drop-in facility, but has a box outside the office door with free Narcan available 24 hours a day and seven days a week.