Caption

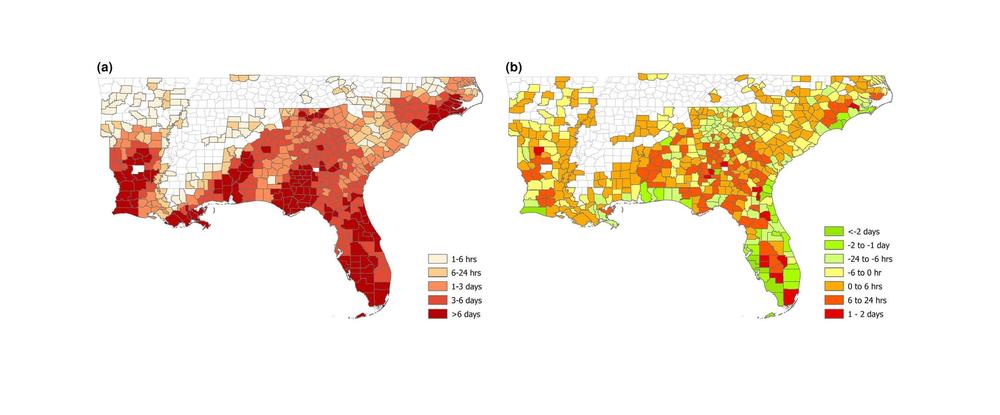

Maps of the Southeast showing average power outage durations over eight hurricanes (left) and power outage durations held for social vulnerability, where counties in organge and red have higher values.

Credit: "Socioeconomic vulnerability and differential impact of severe weather-induced power outages"