Caption

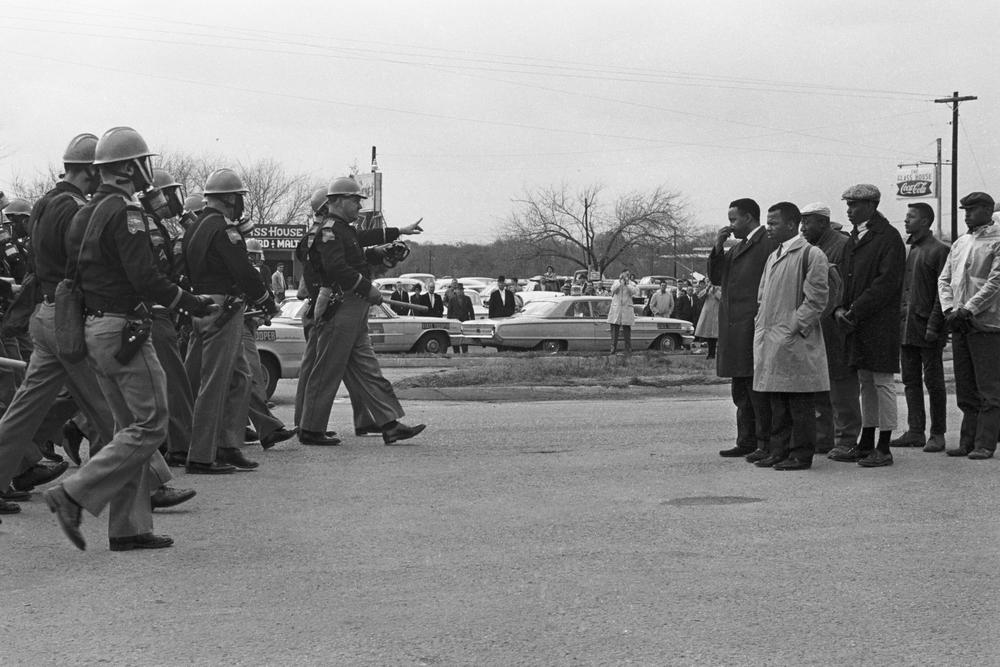

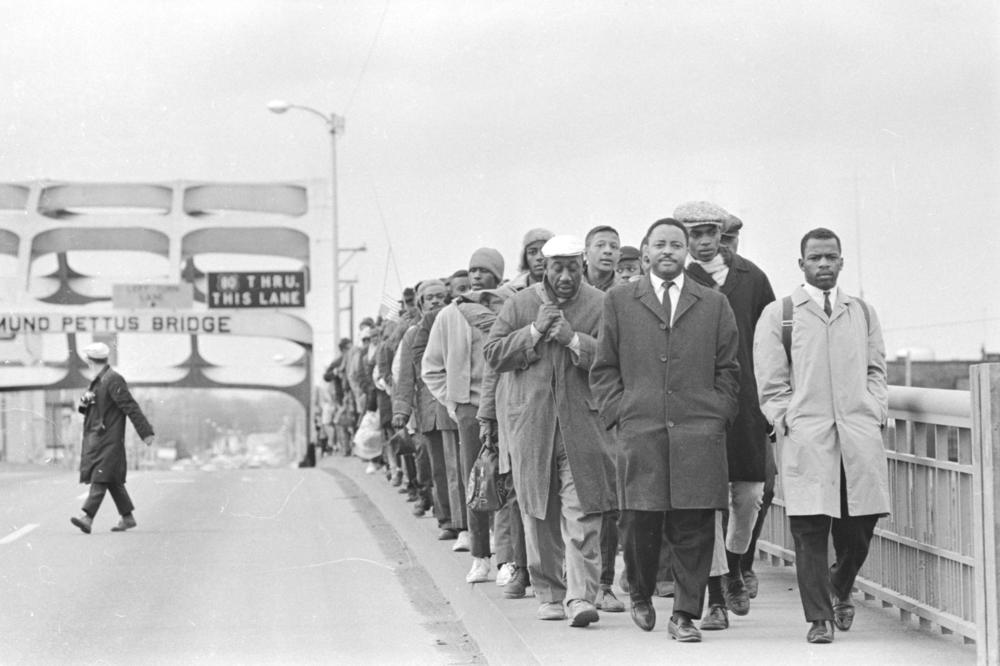

John Lewis with fellow protesters at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, 1965.

Credit: © Alabama Department of Archies and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group. Photo by Tom Lankford, Birmingham News. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.