Section Branding

Header Content

Transforming A Nation & Its Press

Primary Content

As a young child in 1980’s America, the Transformers loomed large in my little girl world. My brother Alden worshipped the heroic vehicles-cum-robots. Like many younger siblings, I loved anything my big brother loved. Optimus Prime and his Autobots hit the mass entertainment market in 1984 and launched a new generation of children’s science fiction.

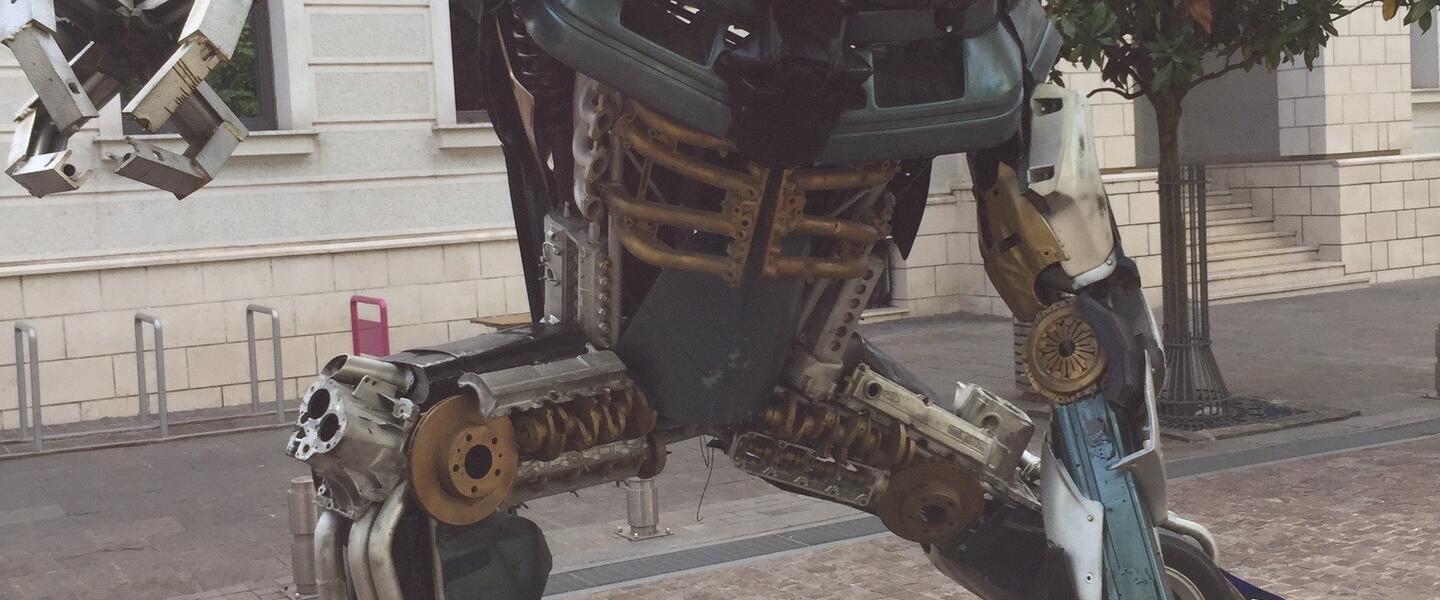

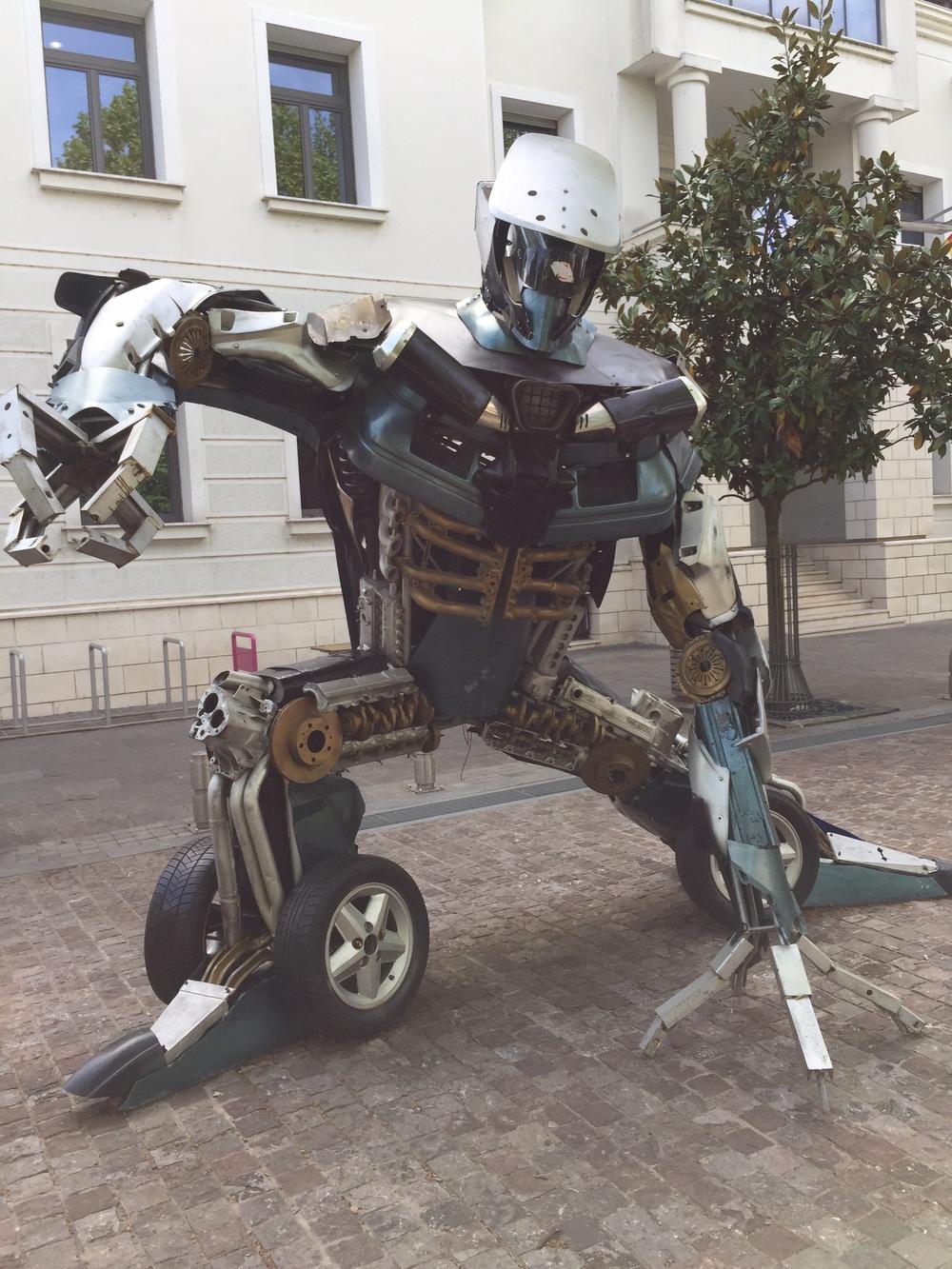

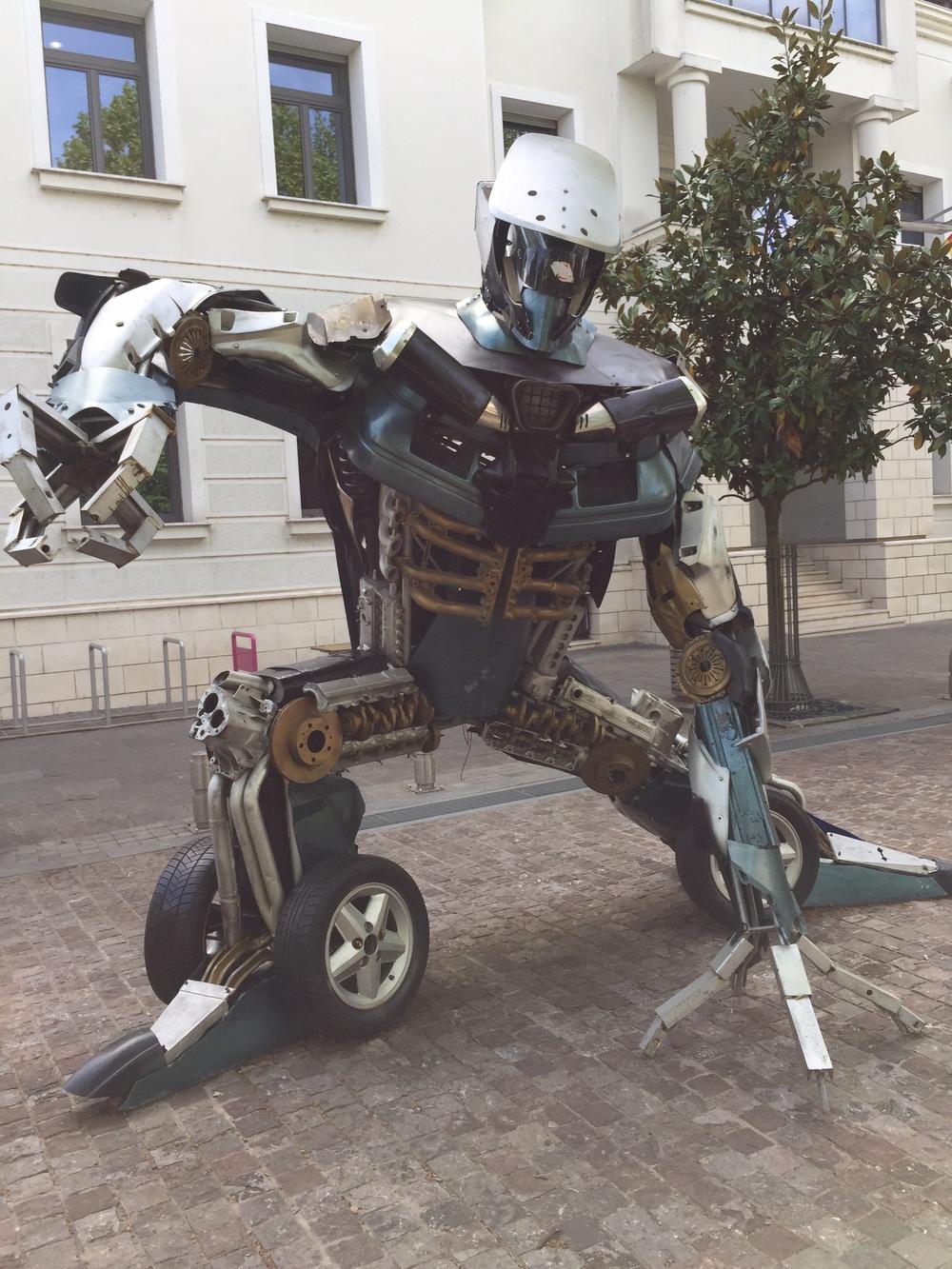

Imagine the wave of Proustian nostalgia that hit me upon arriving in the Montenegrin capital city of Podgorica, where larger-than-life Transformer sculptures hulk over numerous public squares. As the story goes, a young Montenegrin artist erected a version of the morally and physically titanic freedom fighter Optimus Prime. Constructed out of scrap metal, it’s a symbol of the country collecting the pieces of its turbulent history to transform itself into a modern, western democracy. People liked the 50-foot tall figure so much that the artist created more scrap-metal heroes that now peer down onto the streets of Podgorica.

The German Marshall Fund sent me to Montenegro as a Marshall Memorial Fellow. It was one of five stops in my transatlantic journey that also includes Sweden, Brussels, Germany and Poland. My purpose was to study European politics, economic and social policy, and to meet leaders working to improve their home towns and native countries.

Montenegro has a unique history, even among Balkan states born out of post-Communist chaos. The country’s leaders joined Allied forces against Germany in World War I (1914-1918). When the fighting stopped, Montenegro’s national borders were swallowed by neighboring powers. As one member of Parliament put it during our visit, “We are the only winning nation that disappeared after World War I.”

After numerous upheavals, including being part of Tito’s Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Montenegro re-gained its independence 2006. Today, this tiny country on the Adriatic Sea is home to 650,000 people and covers 13,800 square kilometers. It’s “slightly smaller than Connecticut”. It’s also eager to join the European Union.

Getting into the EU isn’t easy. A country seeking EU accession spends several years working to meet standards set forth in 35 “Chapters”. Nations must show that they are functional, organized societies in which politics, business and every day life are free from such obstacles as corrupt government and organized crime. When a country is ready, existing European Union members review the country’s status on each Chapter of standards and vote on whether it should be allowed in. The “yea” vote must be unanimous.

Chapter 10 addresses freedom of the media, a liberty that European Union countries consider fundamental to a free democracy, free market and thriving civil society.

Here is where Montenegro may run into trouble gaining entry into this club of western nations. Reporters Without Borders ranks Montenegro 114th out of 180 countries for press freedoms. Croatia, the most recent European Union inductee in 2013, ranks 58.

One expert I spoke with estimates the country has 30 television stations, 60 radio outlets, and 10 websites. By all accounts, all but one media company buckles to pressure by the Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), the political party that has run Montenegro since 1991 after the fall of Communism. The powerful work to prevent negative coverage of the government and its cronies.

Pressure on a news source can come in numerous forms, from assassinating journalists to preventing an outlet’s advertisers from doing business in the country. According to critics, the latter is the method used to keep the only independent television and newspaper company, Vijesti, in constant financial straits despite high ratings and a wide readership.

One commentator explained, “It was easier when the government directly attacked the paper and journalists because then we had proof - we could make a case - that government is corrupt.” Backroom bullying is harder to prove.

The freedom of a nation’s media reflects the health of its democracy. When a country’s press is afraid to publish the whole and transparent truth, propaganda, fabrication and lies lurk in its newspaper headlines and television closed captioning.

For Montenegro, showcasing Transformer sculptures isn’t enough to transform itself into a bastion of free expression. A commitment to free speech principles and values must take root throughout Montenegrin society.

Such transformation isn’t easy. It requires people who benefit from corruption to voluntarily abide by transparent and fair practices. It requires humility and fearlessness to admit that longterm good for all trumps short-term gain for a few. It requires strong laws on the books, an effective judicial system to enforce the rules, and a populace that uses the tools of civil society to demand free and unbiased information.

In the Transformers’ 1980’s fictional universe, the heroic Autobots and villainous Decepticons begin as unremarkable passenger vehicles and aircraft. It’s only when they transform into fighting machines that we see whether they are good or bad. It’s in their eyes — blue for good and red for evil.

As Montenegrins works to transform their country in the eyes of its citizens, the European Union and western allies, let them choose the clear, clean light of blue to see their way into a free, prosperous and democratic future.