Caption

Anita Collins, Brunswick, was a participant in the Emory University exposure study. April 23, 2025 in Brunswick.

Credit: Justin Taylor/The Current GA

Hal Hart and Anita Collins grew up in the mid-1960s near the briny tidal rivers of South Brunswick, eating shrimp, flounder, whiting and pretty much any local catch on their plates. After high school, Collins moved away — and she soon stopped eating seafood.

That decision is likely the reason that her body is less contaminated with toxins than Hart’s and those of dozens of other Brunswick natives who participated in a peer-reviewed study that examined how residents have been affected by two of Glynn County’s Superfund sites.

The groundbreaking study shows that 40% of the 97 study participants have higher concentrations of a toxicant associated with the defunct LCP Chemicals plant than the national average. Twenty percent of participants had higher concentrations of a second chemical used at the Hercules Brunswick Facility than the national average.

“These chemicals have been in the environment in this area for a long time, but to our knowledge this is the first study to show that they have entered peoples’ bodies, and persist at levels substantially higher than what we would expect in the general population,” says Noah Scovronick, the study’s co-lead author and associate professor of environmental health at Rollins School of Public Health at Emory.

Anita Collins, Brunswick, was a participant in the Emory University exposure study. April 23, 2025 in Brunswick.

The study has sparked community conversations among residents brought up eating the bounty of Coastal Georgia’s waterways — as well as sharpened fear and frustration among those who can’t remember being told of any threat caused by chemicals polluting the environment.

“Those plants provided food on the table, shelter, clothes and sustenance for families. We didn’t think about the fact that what was being produced there was harming the environment; it didn’t cross my mind,” Collins said. “So, to later find out about the environmental harms that have been inflicted on our community. It’s just very mind-boggling, very mind-boggling and painful.”

Glynn County is home to four of Georgia’s 23 Superfund sites, industrial areas that the federal government has declared highly contaminated and needing monitoring and sustained cleanup.

The Hercules Brunswick Facility, which started operations in 1911, extracted rosin from pine tree stumps for decades to manufacture turpentine. In 1948, it started producing the pesticide toxaphene, marketed to protect cash crops like cotton. The company dumped the chemical in wastewater for decades, actions that led to the potent brew flowing into Terry Creek.

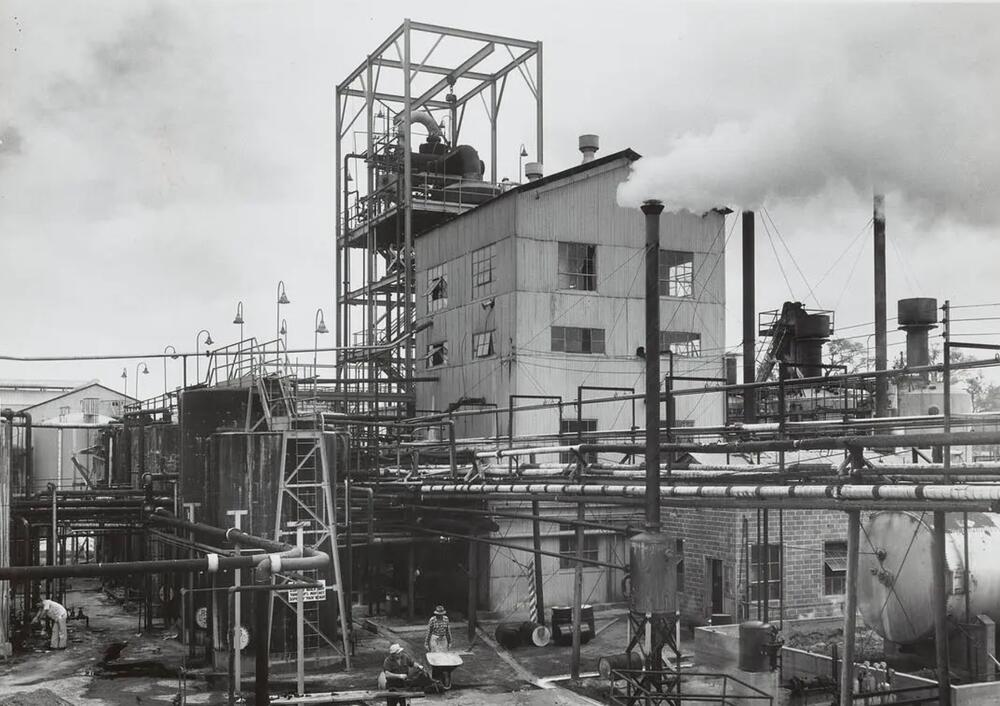

The Hercules Brunswick facility, circa 1960. The plant extracted rosin, turpentine, and pine oil from pine tree stumps to produce a range of chemicals used in the manufacture of varnishes, paints, adhesives, insecticides, textiles, and other industrial products.

In 1990 the United States banned the chemical, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) listed the former industrial facility as a Superfund site in 1997.

Five miles west of the Hercules site, Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) was refining oil. Over eight decades, the property changed hands and industries, before LCP Chemicals started producing chloralkali there. Brunswick area waters soon were polluted by a toxicant called Aroclor 1268, a chemical that was at the plant, and mercury. The 813-acre facility was placed on the Superfund national priorities list in 1996. It is one of Georgia’s largest Superfund sites and the most expansive in Brunswick.

The Superfund law, officially known as the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA), was enacted by Congress in 1980. This law requires responsible parties to clean up highly contaminated land, which they tended to avoid before the act’s passage.

Majority Black neighborhoods grew up adjacent to these factories that later became Superfund sites, and residents there and elsewhere in Glynn County signed up for the Emory-backed study conducted last year.

The study examined two toxaphene components and seven distinct PCBs, three of which are linked to Aroclor 1268.

PCBs are associated with various health impacts on the immune, reproductive, nervous and endocrine systems. TheInternational Agency for Research on Cancer classifies them as carcinogens.

Toxaphene is a chlorinated pesticide that can affect human central nervous systems. The EPA classifies toxaphene as a probable human carcinogen, Scovronick said.

Of the 97 people who participated in the study, the average age was 61 years old. Each participant had lived in Glynn County for a minimum of 10 years, and the average time spent there was 45 years. Of the total, 52 were white, and 40 identified as Black and five others were classified as Hispanic or non White. Sixty-four participants were female.

Scovronick explained that the study did not intend to investigate when or how the toxicants ended up in participants’ bodies. He said that potential pathways include exposure from working at one of the industrial sites or living with somebody who did. Another potential mode of transmission is heavy local seafood consumption, he said.

The study’s results suggest higher exposures for PCBs in Black study participants compared to white study participants.

Anita Collins lived on L Street, two blocks from the Hercules facility, and while no one in her family worked there, plenty of her neighbors and friends’ parents did. Residents looked at those jobs as a source of income, not a danger.

“We were clueless because when you have friends, classmates, and their parents work at these places, you just don’t comprehend what that really means,” she said. “You just know that their father, most times it was their father, had a job at one of these polluting businesses.”

Collins said that the workers she knew who formerly worked at the plant spoke of their jobs as physically demanding. She doubts that they were given or used safety equipment.

Collins, who is of Gullah Geechee descent, said fishing was deeply woven into her community’s way of life. Her family ate seafood from nearby waters weekly.

“The shrimp, the crabs, we had an abundance,” she said.

After high school, Collins left the area in the 1970s to attend college. She frequently returned to Brunswick to visit her immediate family. She’s been living in town full-time for approximately 27 years. After returning, she embarked on a new way of life, including giving up seafood.

Collins bikes regularly and now volunteers as an environmental advocate since retiring as a special education teacher in Glynn County public schools a few years ago.

She would not share her specific results from the study, but described them as not as severe as people she knows from the study group.

“I gave up seafood, so my lifestyle is different, and I recognize that. But even so, changing how I choose to live, I was still impacted,” she said. “Mostly everyone I know who participated, their numbers are high, and I look at it like, that could have been me.”

Hal Hart, 75, grew up on Prince Street, also in the city’s south end, approximately 1.5 miles from Collins, where the Hercules plant was part of his childhood landscape, and a place that helped his father’s hardware store stay in business.

“Hercules, I grew up with it. I used to make deliveries. Ride with the truck. Our store sold things to Hercules,” he said. “It was a good company, and as I got older, I started taking deliveries in there. I would always take a different route to where it was because I wanted to see what the plant looked like.”

Hart moved to the Riverside neighborhood district when he was 13, and that’s where he and his wife still live as they operate his family’s hardware store.

Henry “Hal” Hart has been a fisherman since his youth.

When he’s not at work, Hart is fishing, something he’s done since he was young. Like then, he fishes in the St. Simons Sound, the body of water into which Terry Creek flows.

When he learned about the researchers looking for study participants in 2023, he said he signed up because he wants to try and ensure that his children and grandchildren will be safe, continuing the traditions he grew up with.

When Hart got his study results, he was shocked, but not surprised. He tested above the 95th percentile of Americans for two of the three PCBs that were used and dumped at the LCP site. The concentration of Aroclor 1268 in his body surpassed the average level observed in Americans.

The news made him worried about how to mitigate the threat.

“When I read the test results, I had more questions, and I suspected I had it, but I had more questions of where did I get this?,” he said. “How is this going to affect me? You know, what do I do about this? Is there something that I can do?”

The researchers had blunt news for him and the other participants: There’s not much to be done to get rid of the toxicants stored in their bodies.

Collins said she believes the companies that polluted the Brunswick area should be responsible for paying for more research and health care bills.

The Emory scientists, meanwhile, are looking for more federal money to expand their research and look for links between toxic exposures to health problems.

In late 2023, his team applied to the National Institutes of Health for a grant that would enable them to conduct a suite of new studies. It’s unclear how the proposed federal cuts to scientific research will affect these plans.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.