Section Branding

Header Content

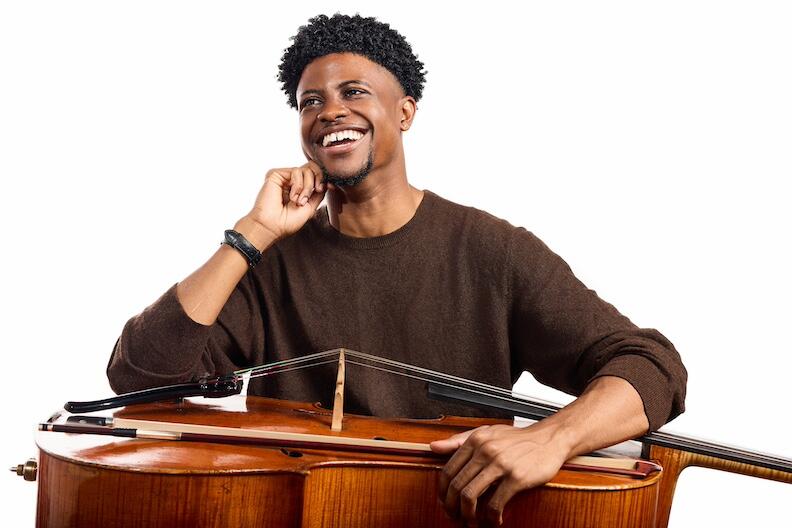

High notes and fast cars: Cellist Sterling Elliott at 25

Primary Content

LISTEN: Cellist Sterling Elliott speaks with GPB’s Sarah Zaslaw.

When Sterling Elliott was a tot in Virginia, just starting cello, his mother told him a little white lie: that cellists get paid more than violinists. Fortunately, by the time the truth came out, he was hooked. At age 19, he won the top prize at the Sphinx Competition, and now, at 25, he performs internationally while finishing up an advanced degree at Juilliard in New York.

In February, Sterling Elliott soloed for the first time with the Atlanta Symphony. Their performance of Haydn’s second cello concerto airs this week on The ASO on GPB. While he was in town, he stopped by GPB to chat with Sarah Zaslaw — about high notes, fast cars, and infusing his playing with ever more life experience.

-

Interview highlights

Edited for clarity and length

On his home musical environment

My mom, though having a job as an environmental scientist, grew up playing the violin. She wanted to bring that love of music to her kids as well, she wanted to have a family ensemble, a family quartet…. By the time she got around to me, the youngest, she knew I had to be the cellist, because we just had three violins. [We played] everything, you name it, whether it was Alicia Keys or Stevie Wonder or the Beatles, or it could be anything from gospel to bluegrass to jazz.

On whether the atmosphere at Juilliard fits its competitive image

I honestly don’t believe so. A lot of your environment depends on the people you surround yourself with, and I think that is largely impacted by who the teacher is. I studied with [the late] Joel Krosnick, who was the head of the cello department, and he’s the most sweet and caring soul ever. So it only makes sense that he cultivates that environment amongst all of us cellists and my studiomates. Perhaps there are some other teachers for certain instruments who are more of the old-school, stricter approach and cultivate an environment that is a bit more cutthroat. But I don’t think it’s the majority.

On what he’s still working to improve

There’s always going to be things, whether it’s the never-ending search for better intonation. Speaking in a more musical sense, as I begin to grow up and gain some sort of wisdom about life, it’s really about being able to inject that into my music. Because at the end of the day, the music that we’re playing, which is so meaningful, so potent, it was all meant to reflect and portray human experience and emotion. The more I’m able to experience that — you know, love, tragedy, heartbreak — there is absolutely a direct correlation on how well I’m able to then portray that emotion, and how potently, into the music. As I continue to live and grow as a human being, which I don’t think will ever stop, I think my music will do the same.

On any hassles of being a cellist

When I was young, everyone would ask me or my mom, you know, “Why did you give the baby the biggest instrument?” or “That thing’s bigger than you!”… One of the biggest things for us is that we can almost never be too loud. So learning about that projection — and this is not to say that the goal is to play as loud as you possible can, quite the contrary — but just learning about that balance as a cellist is a never-ending struggle for us…. I honestly think it’s easier to [fly] with a cello than it is violin or viola. If you bought a seat for it, there’s nothing that can or should go wrong. But my fellow shoulder friends, playing violin and viola, they itch to get on the plane first because their spot in the overhead compartment is not guaranteed, and even if they get their spot they have to worry about someone slamming their suitcase on top.

On why high notes are harder to play

If you were to think about a guitar, you see that the frets get incrementally [closer together] the higher up on the neck or the fingerboard that you go. So every single time you go up higher on a cello or violin, the distance between notes just gets smaller. So the difference at that point between a millimeter of your finger being just tilted right or left, or up or down, could be the difference between a right or wrong note.

On what he thinks about during orchestral intros, before his solo starts

Yeah, that classic concerto introduction. My thoughts and feelings about it, and how long or short that introduction has felt, have changed drastically over the years. Previously, I used to always keep my left hand balled up in a fist on my thigh just to keep it warm, always wanting to prioritize being as warm as possible for the first notes. But honestly, these days I just take in where I am, what’s going on, and just the joy of the music — the delicacy of the orchestral playing and how wonderful they sound, and just the joy of being there, the appreciation of the audience being there, just absorbing it. And these days, honestly, especially last night, it flies by. By the time you blink, it’s time to play.

On his high-speed hobby

When I was around 16, I got into cars. I bought my first car when I was in high school. Before that I didn’t really care about cars, but I was always sort of geared towards the engineering world. Before I wanted to be a cellist, I always wanted to be an engineer. So I love to tinker, and by the time I bought my first car, tinker I did, and just sort of fell into the hobby of modifying [it] — and then building it into more of a race car and racing it.

On how he uses social media (@celloster)

Occasionally I’ll post videos of rehearsals or concerts. But in general I love posting stories and interacting with audiences, whether it’s silly questions like “Would you use this fingering, or this edition?” or “Do you like this shift or that?”

And whom he follows in turn

Xavier Foley is a really unique artist. He’s a bassist who’s making history for bassists and the bass repertoire as we speak. Johannes Moser has always been my favorite cellist. I’ve always loved everything that he’s posted, his playing style, and looked up to him.