Section Branding

Header Content

Overwhelmed with mental health calls, six rural sheriffs make their own plan for better response

Primary Content

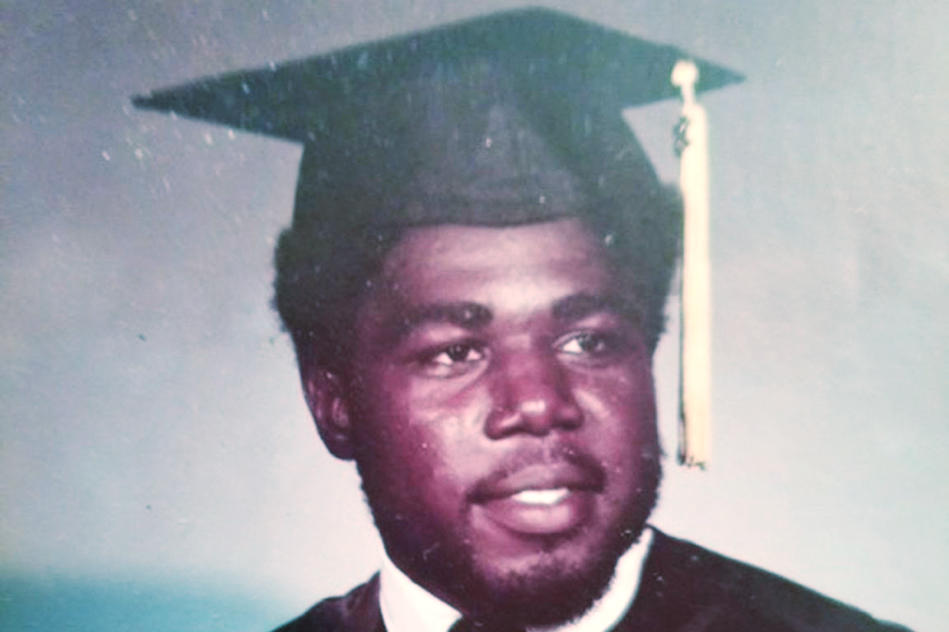

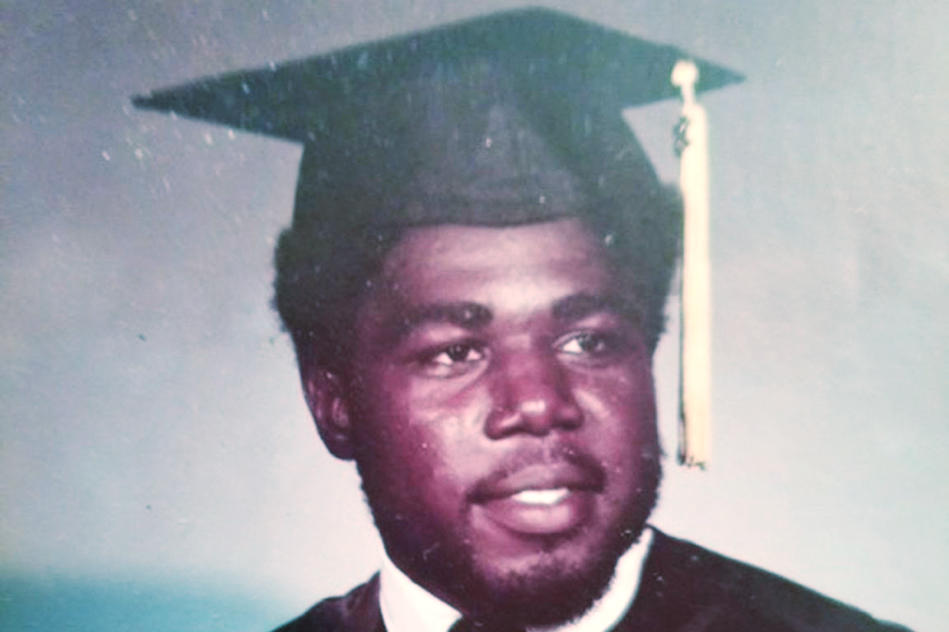

Eurie Martin, 58, was walking alone on a rural two lane road in Washington County in 2017, when three deputies from the county sheriff’s office encountered him, responding to a suspicious person call. They didn’t know Martin had a history of mental illness and were not trained to handle people in crisis.

Police footage shows the situation quickly turned hostile. The deputies are seen crowding him, ordering Martin to “get on the ground.” During the interaction, Martin was shocked by stun gun for over a minute and a half. It was enough to stop his heart.

Emergency medical services were called, but Martin died at the scene in police custody. All three deputies who responded to the call on Deepstep Road stood trial in 2021 for felony murder. That case ended in a mistrial when jurors deadlocked, and though it’s been reassigned, dates for a new trial haven’t been set yet.

Washington County Sheriff Joel Cochran said the case was a turning point for his small community in central Georgia.

“That really opened a lot of eyes to realizing that, you know, we have a crisis in general with mental health,” Cochran said. “And law enforcement is just not trained and capable of handling those types of situations.”

When he took office in 2019, Cochran made 40 hours of crisis intervention training mandatory for deputies to help them respond appropriately to people experiencing behavioral health crises.

Yet even with the training, Cochran says his deputies are overwhelmed with calls about mental health crises. His department is not alone.

Law enforcement are often the first and only ones who respond to calls when people have a mental health crisis, especially in rural areas where behavioral health providers are lacking or completely unavailable.

On these calls, deputies might be out of the county for hours at a time transporting people in crisis to whatever health care facility might have room for them. Due to statewide staff and facility shortages, there aren’t always beds available, and people in crisis can end up waiting in the county jail.

In neighboring Jefferson County, Sheriff Gary Hutchins said his deputies respond to calls about mental health crises every week.

“I would say the last 10 years just got worse," Hutchins said of the problem. "And it's getting worse and worse.”

According to Mental Health America’s State of Mental Health in America report, between 2019 and 2020, 1.3 million adults in Georgia were reported to have had a diagnosable mental illness. That’s lower than the national average, but Georgia ranks near the bottom for access to mental health services, meaning few people receive treatment or counseling.

Hutchins says many of the mental health calls his deputies respond to come from family members of people in crisis, who need help.

“We go a long way sometimes; it could be Saturday night, Sunday morning, 2 a.m.,” Hutchins said. “We don't have a big department. We have three men working per shift.”

Just last year, in neighboring Hancock County, deputies from that sheriff’s office responded to a call for help from 28-year old Brianna Grier’s mother. Grier had schizophrenia and had “an acute mental health episode.” Instead of being de-escalated, Grier was arrested and forced into the back of the car, according to police footage. She died from a head injury after falling out on the road because the rear door hadn’t been shut correctly.

- RELATED: Family of Georgia woman who died after falling from moving patrol car files wrongful death lawsuit

Grier's family is alleging the sheriff's office has “inadequate and insufficient policy for dealing with individuals experiencing mental health crises,” in a wrongful death lawsuit filed earlier this year.

A new 'framework' for change

In many cases, law enforcement officers are not prepared to handle mental health crisis calls. Since 2015, an estimated 20% of people in the U.S. fatally shot by police were experiencing a mental health crisis.

To help address this problem, Georgia put co-response, a model that pairs law enforcement with mental health professionals on crisis calls, into law last year.

Senate Bill 403, or the Georgia Behavioral Health and Peace Officer Co-responder Act, was passed alongside the massive Mental Health Parity Bill, House Bill 1013. The parity legislation lays out a framework to increase the state’s mental health services and provide equitable access to care and treatment, the same as physical health care.

The presence of a behavioral health specialist with law enforcement during a mental health crisis “exponentially decreases the risk of escalation” and helps better link people to the care they need, Senate Bill 403 reads. In other parts of the country, co-response has been shown to de-escalate mental health incidents without use of force.

Existing programs in the state have also shown that co-response works, like the partnership between the Dekalb Regional Crisis Center and the DeKalb County Police Department, the longest running co-response team in the state.

“There's something to be said about someone who is a clinician … That can be soothing, calming, comforting to someone who's in crisis versus maybe solely seeing an officer who is in uniform,” said Shelby Roche, director of the Dekalb Regional Crisis Center. “Well-intentioned, but that already kind of elevates their level of anxiety about what to expect, what's going to happen.”

Roche says co-response has kept people in crisis from the worst-case scenario for the past 26 years.

“We're able to assess and de-escalate the situation where a majority of the people that are reached out to don't have to be transported involuntarily,” Roche said.

Between July 2022 and 2023, over 70% of people in crisis responded to by the DeKalb County Police Department voluntarily went into treatment.

The success of the program relies on a specialized unit of clinicians from the crisis center that are able to individually accompany CIT trained officers on calls. The teams respond to calls from and for people in crisis through the 911 dispatcher as well as those made directly to the crisis center. Earlier this year, this model was expanded to the cities of Dunwoody and Doraville.

Limited funding challenges growth

In Georgia, there are already close to 30 state law enforcement agencies partnered with regional community service boards for crisis responses, and even more pairings of officers with clinicians, according to the Georgia Association of Community Service Boards.

- RELATED: Law enforcement enlists mental health experts to help save lives — 'a paradigm shift in policing’

Senate Bill 403 provides law enforcement agencies a real “framework” to develop future programs, said Carol Caraballo with the office of adult mental health in Georgia's Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities (DBHDD).

“It's kind of like the rulebook or, you know, a guidebook to how we want to kind of move forward with our core responder programs,” Caraballo said.

But getting new co-response programs off the ground in Georgia may encounter a major roadblock — funding. Senate Bill 403 promised state funding for interested agencies, but it’s so far extremely limited.

Earlier this year, the DBHDD said funding co-response teams across the state would cost $15 million. But after Senate Bill 403 became law, lawmakers only set aside $900,000 to establish 10 co-response teams from Rome, down to Thomasville.

Because that funding was directed to the state’s community service boards — centers that provide resources for people with acute mental health issues and developmental disabilities — Washington County Sheriff Joel Cochran’s office was not included.

So Cochran and sheriffs in five other neighboring counties found their own funding: a $1.5 million public safety grant from American Rescue Plan funds, more than all the state money combined.

The plan is to hire and share five clinicians and support specialists to assist deputies on mental health calls in Washington, Jefferson, Glascock, Johnson, Wilkinson and Hancock counties.

“We felt like we can pool our resources together,” Cochran said. “Now will we solve the problem? Obviously not. But our goal is to, one, in responding to these types of situations, be able to de-escalate them so that they don't turn into something a lot worse.”

And, so people in mental health crises live to get the help they need.

Tackling shortages

While state funding lags behind for co-response, workforce shortages present challenges to growing co-response in the state. Most of Georgia has mental health professional shortages, especially in rural areas.

Capt. Trey Burgamy of the criminal investigation unit at the Washington County Sheriff’s Office said they’re looking at the region’s two local hospitals and community service boards to help staff their co-response program.

“We're still in that preliminary part of this: talking to people and finding out which right direction to go,” Burgamy said.

The Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities is tackling another issue too — meeting the rising housing and treatment needs of people with acute mental health issues, many of whom enter the system through interactions with law enforcement.

An independent study presented at an agency meeting in August shows Georgia’s crisis response system is not fit to meet growing demand for services. Over the next five years, the state will need to either significantly bolster its clinician workforce to be able to staff all existing beds at treatment facilities, or add five additional behavioral health crisis centers.

During an agency board meeting in August, DBHDD Commissioner Kevin Tanner said he plans to ask lawmakers during the upcoming session for $15 million to increase the salaries of clinicians staffing crisis centers and $9.5 million for a new behavioral health crisis center in North Georgia.

Sheriff Hutchins in Jefferson hopes lawmakers will make the investment.

“We travel all over the state," he said. "We go to Bainbridge, we go to Rome, and you go to these places but we just don't have the facility for long term [treatment]."

He’s concerned that without enough crisis beds, co-response programs won’t be able to effectively connect people to the care they need as mental health needs continue to rise across the state.

In his eyes, the county must make co-response work.

“It's just overwhelming and we can't handle it,” he said.

Georgia Public Broadcasting is part of the Mental Health Parity Collaborative, a group of newsrooms that are covering stories on mental health care access and inequities in the U.S. The partners on this project include The Carter Center, The Center for Public Integrity, and newsrooms in select states across the country.