Caption

Hardy Frye and Howard Jeffries standing next to the Holly Springs project’s Plymouth with the SNCC logo painted on the door.

Credit: Frank Cieciorka Collection, crmvet.org

Caption

Freddie Greene Biddle is a legacy member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Credit: SNCC Legacy Project

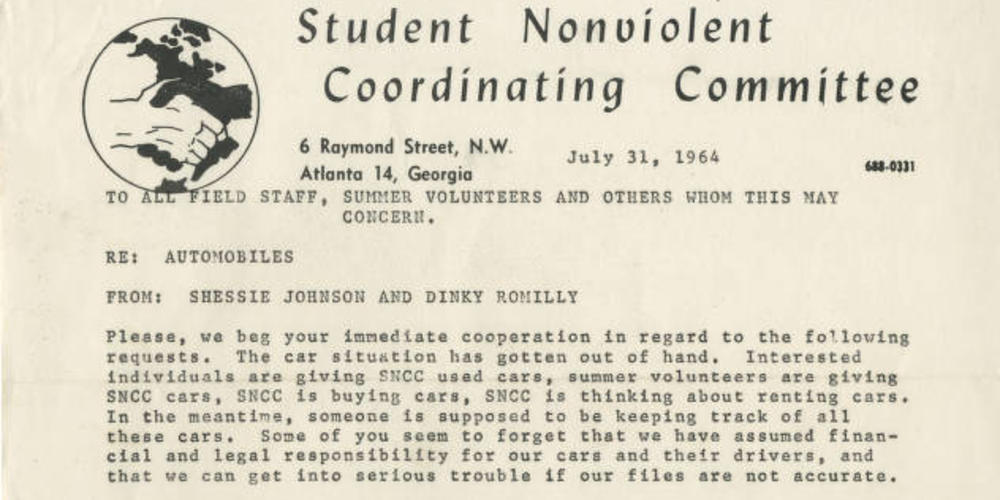

Caption

A Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee memo from Shessie Johnson and Dinky Romilly re: Automobiles, July 31, 1964.

Credit: Samuel J. Shirah Papers, WHS

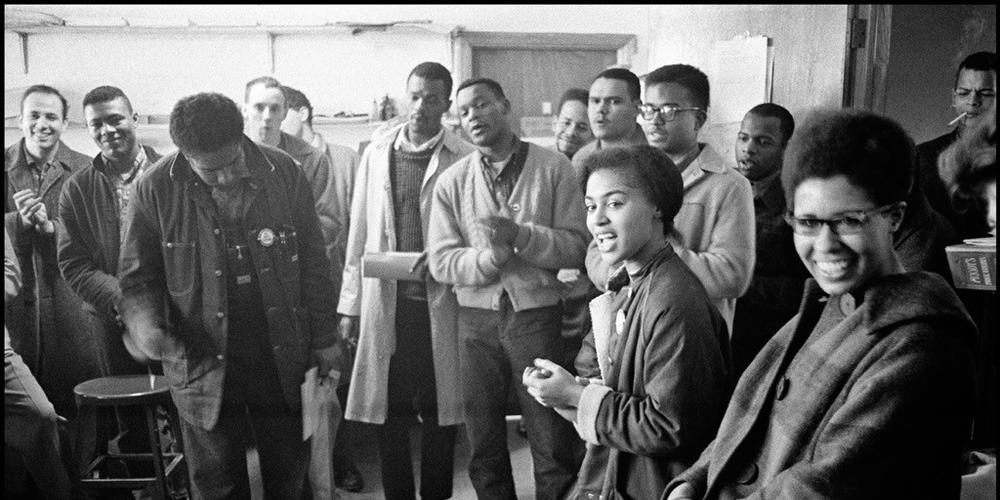

Caption

Judy Richardson pictured clapping in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee's Atlanta office in the 1960s.

Credit: Judy Richardson

Caption

Judy Richardson is a legacy member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Credit: SNCC Legacy Project

Caption

Photograph of Ruby Doris Smith Robinson, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee's administrative secretary.

Credit: crmvet.org