Section Branding

Header Content

Battleground: Ballot Box | The positives and pitfalls of political polling in Georgia

Primary Content

LISTEN: On this week's episode, we look at the good, the bad and the statistically significant parts of polling Georgia's governor and U.S. Senate races.

——

We’re less than a month out from the start of early voting in Georgia’s midterm election, and polls show many of the races are going to be tight.

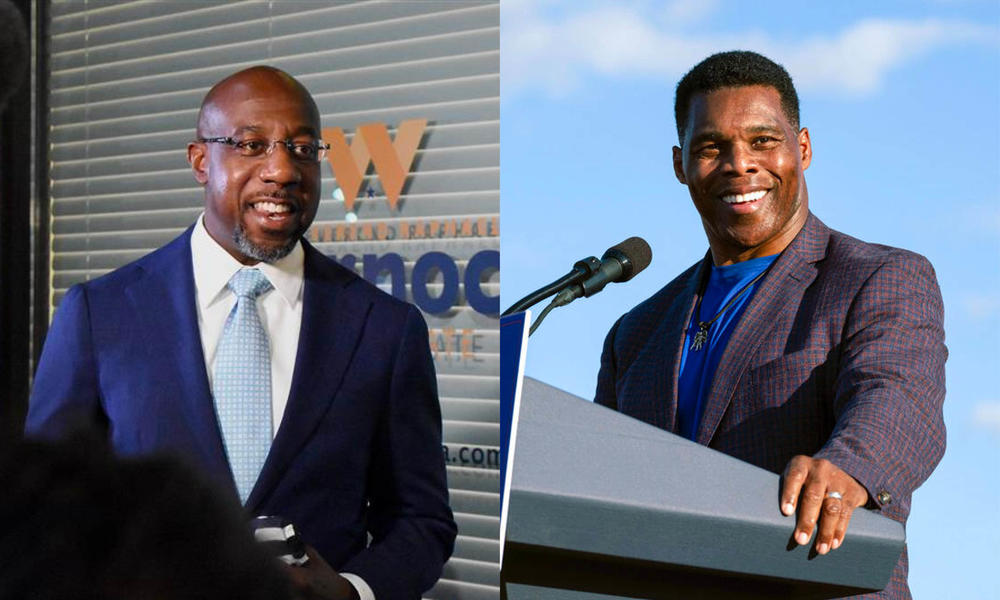

Some polls say Sen. Raphael Warnock will hold on to his seat while others say challenger Herschel Walker could prevail, and Gov. Brian Kemp has varying leads over rival Stacey Abrams — though some are within the margin of error to suggest it is statistically tied.

Who’s right? Who’s wrong? And who is going to win?

The answer is less complicated than you think, but it requires a better understanding of what opinion polling can and cannot tell us.

This week we’ll talk with two top experts and break down the good, the bad and the statistically significant parts of political polling.

There’s a common refrain in the political sphere that the only poll that counts is the one on Election Day, but public opinion polling about campaigns and issues do serve a valuable role in capturing sentiments ahead of an election.

So what exactly is a poll?

"The first thing that pollsters love as a saying, is to say that it's a snapshot, it's not a prediction," said Ariel Edwards-Levy, polling and election analytics editor at CNN. "What you're doing is you're talking to a random sample of a certain number of voters across the state, and that group of people who you talk to hopefully will represent the larger electorate. And what it will tell you is, if the election were today, what those people think they would vote for, what their vote choice would be."

Edwards-Levy says there are many potential failure points, even within that description of a poll. You might not get a group of people that represent the electorate as a whole, or might be a different demographic breakdown than who actually shows up and votes — or voters could change their minds.

"But it does give you, for the most part, a generally good sense about the state of a race: whether it's close, whether it's not close," she said. "So it can really sort of give you a sense on the ground that can help you understand the race beyond what you might know just from hearing what the campaign says or talking to people around you."

Take Georgia’s U.S. Senate race, for example. Overall, more recent polls find voters saying they would support incumbent Sen. Raphael Warnock than Republican Herschel Walker, but usually by just a few percentage points. In this particular snapshot in time, you could say that Warnock is in the lead among those voters that were asked that question in those polls.

But how are pollsters able to paint that picture by asking only several hundred to a few thousand people? By capturing a representative sample of the voting population, and there are two ways to do that.

"One is by sampling, which is how you find the people who you're surveying," Edwards-Levy said. "And one is by weighting, which is how you look at those numbers after you've talked to people to make sure that they actually do reflect the electorate that you want to see."

It used to be pretty easy to get a random sample of phone numbers, call people up, and get a pretty representative sample of voters, because it used to be that everyone had a landline and usually answered the phone. Nowadays, the rise in cellphones, spam calls and a move towards digital communications means polling has had to adapt.

That means things like using a voter file of public data to find additional demographic information, polls conducted through text messaging or postcards or online and other innovations to reach people where they are — with new challenges in creating representative samples, too.

Edwards-Levy says how pollsters reaches out to potential participants is one of several transparency factors that separate a reputable, reliable poll from one that should create some skepticism.

"As a minimum standard, you should not be willing to take at face value a poll where the pollster is not very willing to talk about, 'How did we conduct this poll? Who is it done on behalf of? Who did we talk to? How did we find them? What exactly did we ask them?" she said. "Polling data is not magic. You should take it with the same sort of skepticism that you'd apply to any sort of news where you would want to say, 'Well, okay, how do you know that? How do you know what you're telling me?' So I think that is just sort of the absolute baseline."

That’s something that Nathaniel Rakich, senior elections analyst at polling outlet FiveThirtyEight, agrees with.

"In the end, the goal is to get a sample that looks like whatever broader population you're trying to poll," he said. "So in the case of Georgia, you'd want to make sure that the racial composition is similar, you want to make sure that the age composition is similar, the gender composition... other folks will weight by other variables."

Another variable that is important to consider when looking at poll numbers is the margin of error, which accounts for the variation that comes with only talking to a sample of voters instead of an election, which technically talks to all of them.

Take a hypothetical example poll that has Kemp at 48% and Abrams at 44% with a 4% margin of error.

"In that hypothetical 48 to 44 poll, if it is a plus or minus four point margin of error, it means that Brian Kemp at 48% could be as high as 52%, he could be as low as 44%," Rakich said. "And it means that Stacey Abrams from her number at 44% could be as high as 48% and could be as low as 40%."

Polling experts like Rakich and Edwards-Levy say you should consider horse-race polling matchups like these as a range of likely outcomes, and with many Georgia polls for Senate and governor being within the margin of error you should come to the conclusion that they are very close races.

"I think the best way to treat it is the way that you would treat any other information that you see about a campaign, which is to look at what it does tell you and not try to turn it into something that has all the answers or has exact answers, because if you do that, it will be useless," Edwards-Levy said. "But if you accept the limitations the polling does have, it can really tell you a lot about the state of the political environment, the state of the state around you, and sort of what you might want to know about the upcoming election."

A look at recent Georgia polls

According to the Associated Press’ VoteCast survey after the 2018 midterm elections, 63% of that election’s voters in Georgia were white and 31% were Black, 53% of voters were women, and 22% were over the age of 65. Stacey Abrams narrowly lost that year by about 55,000 votes. Two years later in the presidential race, the share of white voters slightly increased while the share of Black voters and those over the age of 65 decreased.

It’s impossible to know who and how many people will show up to vote in 2022, but even the slightest shifts in demographics and turnout could change who wins — and could change how polls could be interpreted.

Take the most recent Quinnipiac governor’s race poll conducted Sept. 8 through Sept. 12. Pollsters talked to nearly 1,300 likely voters, and have Kemp up by 2 with a margin of error of 2.7%. Based on our newfound poll evaluation knowledge, we should read that Kemp is likely ahead, but the race is quite close.

Digging deeper, the poll also shares its cross tabulation report, or cross-tabs, which looks at relationships between different subgroups, like “White people who support Brian Kemp.” The Quinnipiac poll’s crosstabs don’t show the specific share of voters that have demographic characteristics, but their support for the two candidates largely matches 2018.

For example, 2018 AP VoteCast data showed 25% of white voters supported Stacey Abrams, and the latest poll has her at 26% with that subgroup. Across the board, that poll with Abrams behind by 2 points has her performing about the same as 2018, when she lost by 1.4 points.

Even these subgroups have their own margins of error depending on how many people responded, so the crosstabs should be taken with their own grains of salt at times.

"The other thing is context, because there are a lot of polls out there," Edwards-Levy said. "At a certain point, I'm not saying take every single poll equally, but it does make sense to sort of look at things in context as a whole. Is this something that's showing something radically different than all the other polls are finding?"

Take four recent Georgia polls that all show Herschel Walker ahead of Warnock. Are they signs that the Republican is ahead in this crucial election time, or outliers that should merit further examination?

For starters, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution/University of Georgia, Fox5/Insider Advantage, Emerson and Trafalgar polls all have margins of error greater than Walker’s margin over Warnock, so the proper way to read them is as the race being a statistical tie. Meanwhile the well-established Quinnipiac poll has Warnock up by 6 points, outside the margin of error.

In this case, a deeper examination yields some possible explanation.

InsiderAdvantage and Trafalgar did not share their crosstabs or detailed methodology of their polls, so that raises some questions about who they spoke to and how it compares to the likely electorate in November. The AJC/UGA poll has a sample that is older than the average electorate and more than 50% Republican, potentially a higher share than what this fall's electorate will be, too.

Outside of traditional polls, you also need to be aware of partisan pollsters, and polls released by campaigns or issue groups.

"It's not that campaign pollsters aren't good — they have very powerful incentives to get it right for the campaigns they're working for to make sure that they're giving them good data," Edwards-Levy said. "But if they're releasing data, then their incentive to do that is often to try to influence discussion, which means that they're not going to necessarily release numbers that don't tell the story they want to tell."

So when the Stacey Abrams campaign’s internal poll has her down two points to Brian Kemp, that doesn’t mean it’s right or wrong, but that you should consider the source and look at what other information they release.

As we head into the final days of this election cycle, it’s appropriate to operate under the assumption that Republican Gov. Brian Kemp and Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock have the advantage headed into the election, and that the cliche of who shows up to vote will decide the actual winners.

And it’s appropriate to take a more measured response to any polls that come out between now and then and consider all of the information when trying to figure out where things stand.

There are certainly pros and cons of reading polls both individually and writ large.

"Polling is certainly our best tool for measuring how people feel about an issue, how people plan on voting in an election," Rakich said. "But it is not perfect and there are lots of ways that it can go wrong. It usually doesn't go wrong by that much, but it can sometimes be important in a state like Georgia where in recent years you've had some very close elections."

Edwards-Levy says you’ll give yourself a headache trying to go in-depth on every single poll and every single race, and should focus on the big picture instead.

"To go back to the snapshot analogy and maybe belabor it a little bit further, it's a lot of people taking snapshots of varying blurriness from varying cameras, of varying quality, from different angles," she said. "And if you put them together and you look at them all together, you can sometimes get a pretty good picture of what the state of the race is. So if you're seeing a bunch of polls saying the race is pretty close, I think what you can take away from that is this is a fairly close race."

The next time you see a push alert telling you that so-and-so poll has your desired candidate up or down, be sure to look at the bigger context, consider the source and, in case you forgot, remember that Georgia is a battleground state and most elections will be closer than not.

Battleground: Ballot Box from Georgia Public Broadcasting is produced by Stephen Fowler. Our editor is Josephine Bennett, our engineer is Jake Cook and Jesse Nighswonger wrote our theme music. You can subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts or anywhere you get podcasts. Thanks for listening.