Caption

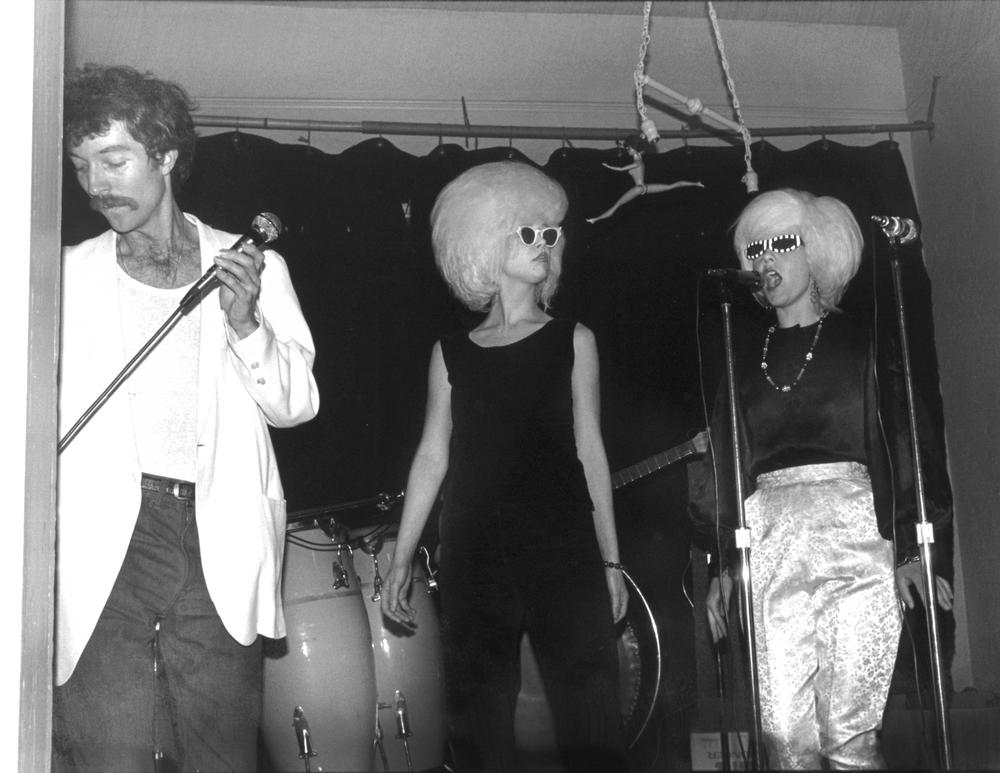

Fred Schneider, Cindy Wilson (middle), and Kate Pierson of the B-52’s perform during the band’s debut at an Athens, Georgia Valentine's Day party.

Credit: Photograph by Kelly Bugden; Courtesy of Keith Bennett

|Updated: August 28, 2020 6:37 PM

"On Second Thought" host Virginia Prescott speaks with Grace Elizabeth Hale.

Fred Schneider, Cindy Wilson (middle), and Kate Pierson of the B-52’s perform during the band’s debut at an Athens, Georgia Valentine's Day party.

Athens, Georgia was a sleepy Southern college town in the late 1970s and early ‘80s. Bulldogs football and an established fraternity and sorority scene dominated social life on the University of Georgia campus.

But something else was percolating in the shadows of Milledge Avenue: a creative underground as vibrant and subversive as any you might find in the country’s major cities. It was in this period that Athens became the site of one of the most influential regional music scenes of the late 20th century, spawning ground-breaking bands like The B-52’s, Pylon, R.E.M., and countless others.

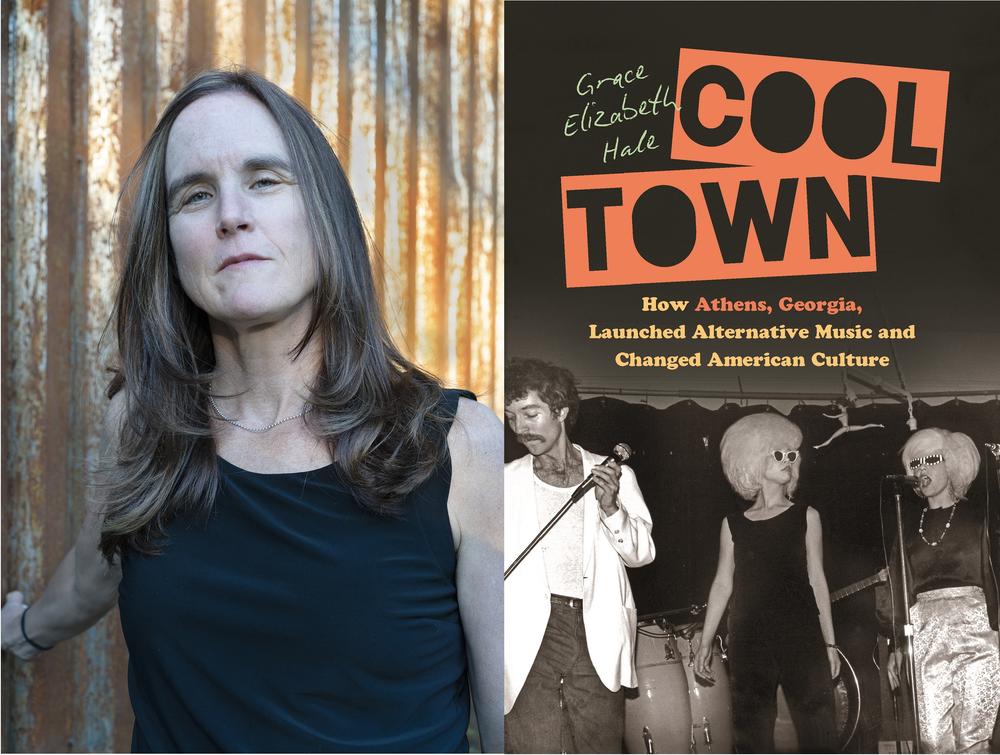

Author Grace Elizabeth Hale's new book is called "Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture." It was released in February 2020.

Historian Grace Elizabeth Hale follows the evolution of the small-town musical mecca in her new book, Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture.

Hale makes the case that, guided by experimental art, a DIY spirit, and progressive politics, the Athens scene allowed Georgia kids to consider the possibilities of a creative life – right in their home state.

Grace Elizabeth Hale was one of those kids. She got her undergraduate and graduate degrees at the University of Georgia, joined a band, and opened a small music venue during the heyday of the Athens scene. She's now a professor of American studies and history at the University of Virginia. In the intro to the book, Hale writes:

In Athens, Georgia, in the 1980s, if you were young and willing to live without much money, anything seemed possible. Magic sparkled like sweat on the skin of dancers at a party or a club. Promise winked underfoot like the bits of broken glass embedded in the downtown sidewalks. A new world seemed to be emerging out of our creativity, our music and art, and our politics, but also the way we understood ourselves and related to each other.

Athens bands like the Bar-B-Que Killers played often at a club in Atlanta called the White Dot. Left to right: David Judd, David Barbe, Arthur Johnson, Laura Carter, and Claire Horne.

She goes on to say: “We were unlikely people in an unlikely place. No one expected us to do these creative things. No one who mattered thought that we could make a new kind of American bohemia."

Hale joined On Second Thought host Virginia Prescott for one of the Atlanta History Center’s virtual author talks to discuss her book and the so-called “Athens Miracle.”

Cool Town follows a through line from Andy Warhol’s Factory and the drag scene in New York City to the surprisingly robust Athens queer community that predated the music scene — all of which inspired the Athens scene’s rejection of the mainstream culture’s values.

As improbable as an indie music scene might have seemed in Athens, there were a number of factors that helped nurture its growth. That included the University of Georgia Library – which provided both cultural and practical information for the budding scene – as well as the school’s art department. Hale says those art world influences fueled the creativity and originality of the music scene, particularly for the band Pylon.

“For people like Michael Lachowski and Randy Bewley from Pylon, creating a band was just another form of art,” she explained. “It was like performance art. And the instruments – musical instruments – were just other kinds of tools they could learn to manipulate.”

And while some bands, like The B-52s, left Athens to pursue greater success outside of the South, it was the town’s very “Southernness” – influenced by local artistic traditions – that launched a lasting regional movement.

That’s because bands like R.E.M., after a period of negotiating their relationship to their home, began to embrace their roots and mold a new narrative that blended a bohemian, folky, and rural spirit. And, for their fans, it provided an alternative vision of what it could mean to be from the South.

“I think that was a huge part of the appeal of R.E.M. in that period for a lot of their fans – not just in Athens, but across Georgia, across the whole Southeast – was that way that they were presenting a kind of a different way to be a white Southerner,” Hale said.

And this early scene, which could have otherwise faded away, left a lasting mark on the unlikely Southern city, branding it as a haven for artistic, creative and eccentric Southerners in the decades that followed. Hale points out that Athens continues to nourish – and even broaden – its arts and music scene.

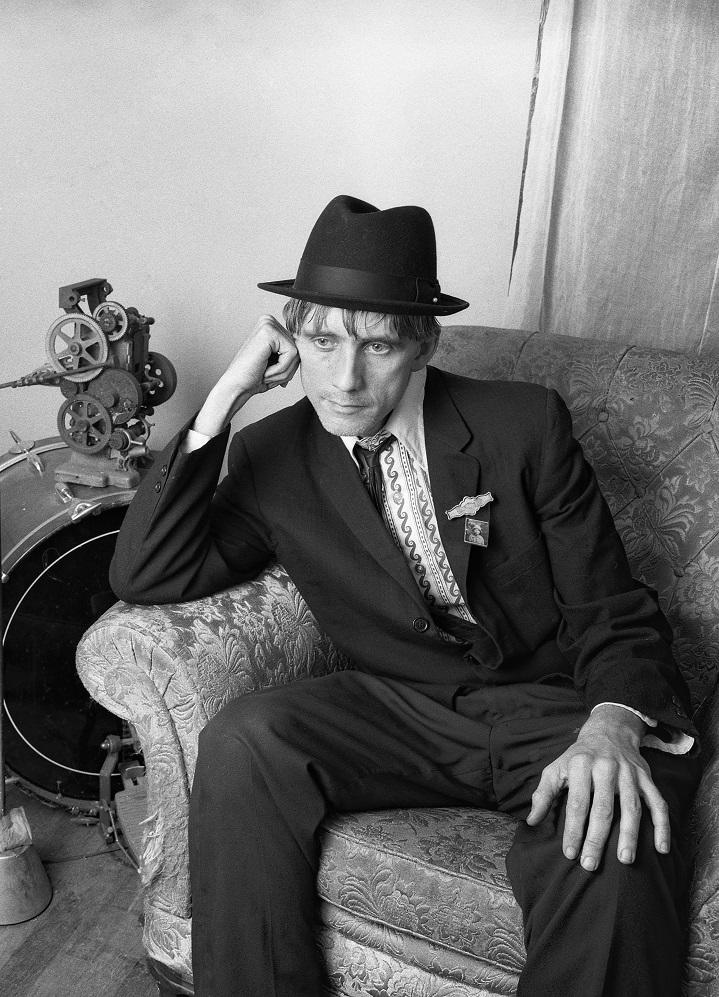

Hale says no other single figure did more to nurture the Athens scene than Jerry Ayers, who changed his name to Jeremy Ayers in the mid-eighties.

“Athens is not over by any stretch,” she said. “You know, there are more bands than there ever were. There are, at any given moment, hundreds and hundreds of bands in Athens, and there is a kind of community of musicians and creativity. And it's now a community that has grown and changed in ways that it actually includes hip-hop artists, for example. The Vic Chesnutt Songwriting Award, [in] many of the recent years, has been won by hip-hop performers. So it's still an incredibly exciting, vibrant music scene.”

Check out Grace Hale’s Cool Town Athens Playlist on Spotify!

This audio is an edited version of the conversation, but you can hear (and watch) the full interview here. The virtual author talks, which are free events, resume on Thursday, Sept. 10 at 7 p.m. with Claudio Saunt. For a full schedule and Zoom links, visit the Atlanta History Center’s website.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

On how the University of Georgia library impacted the development of the Athens scene

The absolute key thing for the scene was the fact that the University of Georgia libraries were wide open. You didn't have to be a student to use the library. These were the ways that people had in that period to actually watch old films, or films from other parts of the world, or to listen to music across the history of musical recordings. We didn't have anything like Spotify, or Apple Music or any of the other ways. And so the library was – for the young folks that made the Athens scene, it was like their Internet. It was their place to go to be inspired, to find out things about the world, and also even when they needed practical information. I mean, when The B-52’s were being approached by record companies before they signed their big deal, Ricky Wilson went to the University of Georgia Law Library to look up contracts to figure out how to negotiate their contract. So, from the practical to the more aesthetic and artistic, and even philosophical, the libraries were absolutely key.

On how The B-52’s were influenced by the New York art scene, and brought it back to Athens with them

And after [Jerry Ayers] went up to New York City, he invited Keith [Strickland] and Ricky [Wilson of The B-52’s] to come up there and visit him, and they got to go to [Andy Warhol’s] Factory and hang out with the famous drag queens like Jackie Curtis. Jerry at the time was one of Andy Warhol’s drag queen superstars; he went by the name Silva Thin. And they just got to be a part of this incredible, creative milieu there. And so when they came back to Athens, they were like, “We're going to do that here. We want to just keep that spirit going here. Why can't we just do that here?”

So they would dress up and just wear completely insane outfits and parade around the town, or put on an impromptu performance in an all-night laundromat. They would just do the craziest things: set up their furniture from their house beside the road and just sit there all day in a kind of like Dada art project. They just brought this spirit. And I think people are now so used to Athens having that kind of eccentric music, art kind of world. But back then, this was really, really wild. You know, it really, really stood out in a town that was really mostly known for football and for the Greek system at the university.

The B-52’s perform at Memorial Hall on the campus of the University of Georgia in November 1978.

On how the Athens scene rejected or reflected established disparities in the larger culture

I think one of the things that you really have to keep in mind is that for people that were participating in the scene, it looked so much better than any of their other options. So the trick is to sort of acknowledge the limitations, the ways in which the scene recapitulates some of the sexism of the larger culture, for sure. You know, back then there actually was mainstream, a powerful mainstream in America. And that world in the South at the time for women was very constraining in ways that the scene was not. And so, there's more freedom to do things that you wouldn't have been able to do. So many Athens bands have women members, for example. And that is hugely the result of the stress on amateurism, which actually makes space for women who are less likely to have spent their entire, you know, junior high and high school years noodling on a guitar in their room than men – traditionally in this moment. Some of them did. Sure, there are always exceptions, but the amateurism really made space for them.

And the same thing is true, I think on the racial front. The mainstream culture at the University of Georgia was very, very outwardly racist. And so the fact that the scene rejected that kind of explicit white supremacist, kind of neo-Confederate apologistic Southernness – which was very, very strong in this period, right? This is the time period, of course, when people are waving Confederate flags at football games, for heaven's sake – is an advance over what the other option is. And yet at the same time, not where we'd want it to be today … in terms of race. There are people of color in the scene, but it is a mostly white scene. And that is in large part, I would argue, because they're drawing from a mostly white college student population. The second thing, though, is that the scene is not very attractive to the working-class African Americans who live in Athens. Thirty to 33 percent of the population of the town is African American at this time, mostly working-class African Americans. Their musical world is very much the opposite of amateurism. It's about craft! It's about being an amazing, amazing performer – practicing all your life, really playing your instrument well. Those people are like, “We're not going to go to the 40 Watt [Club] and pay money to see somebody who doesn't know how to play. Like, that's ridiculous! Like, that's why would you want to do that?” So there is a kind of mismatch there in terms of what they're thinking music and artistry should be. And that has an effect as well.

On R.E.M.’s shifting relationship to their “Southernness”

After [R.E.M.] get signed to I.R.S. [Records] and they're putting out their Chronic Town E.P., and even before Murmur, there's this fear that Athens is over. That music scene is done. You know, The B-52’s have come and gone and all these people are putting out records – Love Tractor, Pylon – and now you're going to put out a record too, and be another Athens band. And there's going to be a backlash against that; that's what the record company is telling them. And they're fearing it, too! And so, you can find this little moment, if you read the interviews that they're doing in ‘82, ‘83, where they're like, “We're not an Athens band! We just live there. We don't sound like those other bands! We're not, like, connected really to the South. That's not our thing!”

And then, of course, they double down. … They come out with Murmur, with the kudzu on the cover. And then they come out with Reckoning, which is such a Southern album in so many ways, and even more so, I would say Fables of the Reconstruction. I think that's a really interesting thing about R.E.M., the way they're negotiating their relationship to Southernness.

And I think they do a lot to create an image of a kind of Southern folk artist, bohemian rural-ness that is a kind of alternative South to the other images of the South that are circulating – especially what white Southerners can be at the time, when people really are thinking of white Southerners as racist idiots, in other parts of the world. And I think that was a huge part of the appeal of R.E.M. in that period for a lot of their fans – not just in Athens, but across Georgia, across the whole Southeast – was that way that they were presenting a kind of a different way to be a white Southerner.

On the first time Hale came across a key figure in the Athens scene, Vic Chesnutt

I encountered him one day sitting very near The Arch [at University of Georgia], behind a rickety card table, passing out pamphlets. And he looked just like one of those proselytizing, you know, the preachers that always go down there and try to save souls. I thought, actually, he was handing out “The Watchtower” when I first saw that he was sitting there. And you had to get really close to him; he was sitting in his wheelchair behind this card table. And he had a poster board with something written on it like “God is dead” or “God doesn't exist.” And he was handing out pamphlets about atheism. But he was doing it in exactly the same way that someone proselytizing for Christianity would. And, as someone who was creeping my way from agnosticism to atheism at the time … this was just amazing. I had no idea that he would go on to become one of my very, very favorite songwriters and musicians of all time. Had no idea even he was a musician! But I thought, “This is the best piece of performance art I have ever seen” – that this guy is doing this at the University of Georgia in the early ‘80s. It was profound.

Pylon broke up for the first time in late 1983, at what seemed to their local fans like the height of their fame.

On if – and how – the Athens spirit of “anything is possible” continues today

I think it's out there happening now, and it's just not happening in ways that look familiar to somebody circa 1985. It's thinking about, for example, the kinds of incredibly creative culture around [the] making of memes, Internet memes and gifs. I mean, to me, that has the same kind of spirit of creativity, of DIY, of “We don't really think this is going to turn into a job, but we've got something to say and we want to put it out there in the world.”

I guess that I would say that I think that these spaces exist. They could be nurtured and supported better. We could value them more. Maybe we will after this time of pandemic – being stuck without this kind of face-to-face community – maybe we will value those kinds of interactions more and nurture that more. But I think that it's presumptuous of me as an older person who goes to bed early to suggest that these things are not still going on. So I don't lecture my undergrads on that. I try to tell them about what happened in the past and what they can take from that, forward.

Get in touch with us.

Twitter: @OSTTalk

Facebook: OnSecondThought

Email: OnSecondThought@gpb.org

Phone: 404-500-9457