Section Branding

Header Content

CDC Study: Black, Brown Children More Likely To Be Hospitalized With COVID-19

Primary Content

Children who contract COVID-19 most often experience mild symptoms if any, according to a recent study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

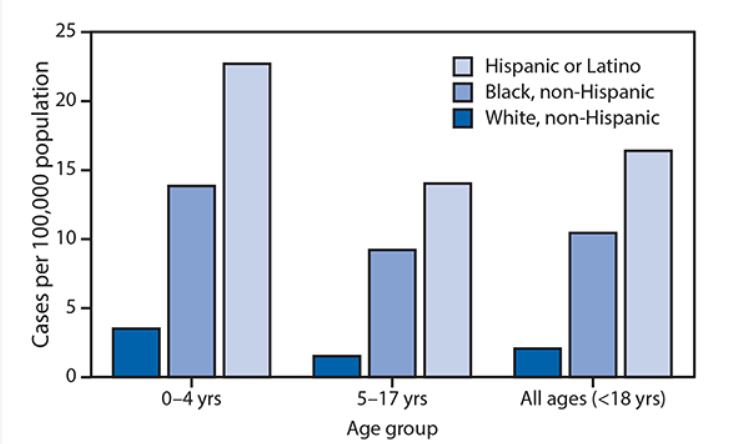

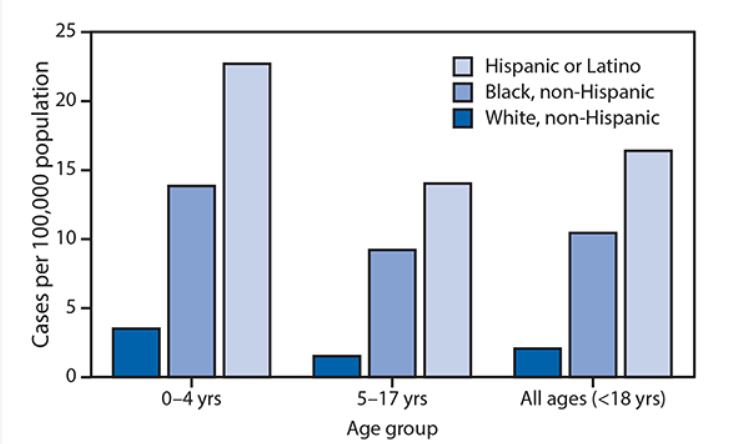

But, of those in the study, Black and Hispanic children more often needed hospitalization, accounting for more than 75% of the cases.

"COVID-19–associated hospitalization rates were higher among Hispanic and Black children than among white children," the study said. "The rates among Hispanic and Black children were nearly eight times and five times, respectively, the rate in white children."

Dr. Monique Smith, an Atlanta-based emergency physician with an interest in racial disparities, said communities of color are often more vulnerable for socioeconomic reasons.

Outbreaks of coronavirus nationally occurred often in places that traditionally had larger Hispanic and Black populations, such as the chicken processing plant in Gainesville. These are more often communities with people considered essential workers, who are on the front lines in the pandemic, Smith said.

PREVIOUS COVERAGE: Northeast Georgia COVID-19 Hotspot Spurs Action In Poultry Industry, Latino Community

There's a digital divide across professional, educational and health care sectors, Smith said.

"They can't necessarily afford or have the opportunity to work from home," Smith said. "Those individuals have to come back home and have to take care of their kids."

The CDC study looked at 576 pediatric COVID-19 cases in 14 states, including Georgia, reported to the COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network between March 1 and July 25, 2020.

The study considered children those aged 17 and under. One of the 576 hospitalized children, 208 spent time in an intensive care unit and one died from the effects of COVID-19.

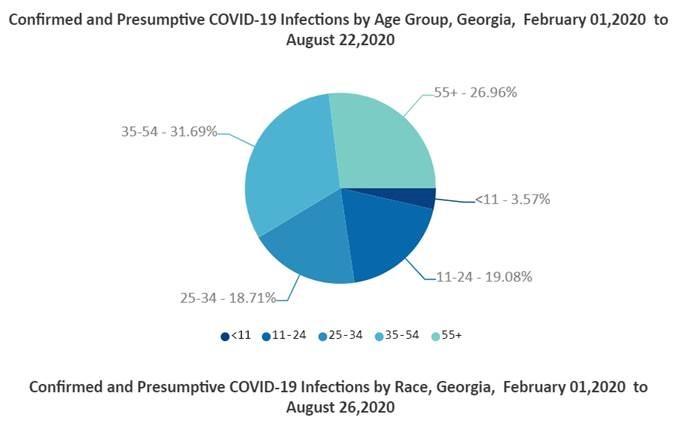

Georgia's state health department as of Aug. 25 has reported four pediatric deaths.

Among 526 (91.3%) children for whom race and ethnicity information were reported in the CDC's study, 241 (45.8%) were Hispanic, 156 (29.7%) were Black, 74 (14.1%) were white; 24 (4.6%) were non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander; and four (0.8%) were non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native.

A number of different factors go into the inequities seen across health care and society as a whole, Smith said.

What the study really showed is that children who suffer from underlying conditions such as obesity or chronic lung disease were more likely to suffer serious side effects from COVID-19, Smith said.

The socioeconomic factors include things like access to childcare and even health care.

"We're talking about maternal morbidity and mortality, which we know are higher in Black and Hispanic populations," Smith said. "Those are the children who were showing up and being hospitalized for comfort within this study."

Georgia ranked worst in the nation for maternal mortality in 2018. That means there are scores of women in the state who cannot obtain the health care they need, even with access to Medicaid.

RELATED: Lawmakers Consider Maternal Mortality Bill In Final Days Of Session

Rep. Sharon Cooper succeeded this year in getting a bill passed that increases the time a woman has Medicaid from two to six months after giving birth.

Prematurely born children are more likely to suffer effects of asthma, which puts them at higher risk of complication from COVID-19, Smith said.

"We have the data that shows us which communities are more socially vulnerable across this country," Smith said. "There's a correlation there between social vulnerability of a community and the number of cases and fatalities of COVID-19 in that community."

Maps of COVID-19 and how they're disparately affecting communities of color very much resemble maps of maternal mortality, Smith said.

"When you see that, you have to think of the social determinants of disease that lie behind that," she said. "So is that about your access to health insurance, your ability to get care, your ability to have nutrition and stable housing during your pregnancy?"

Additionally, the existence of food deserts in Georgia add to the problems of obesity, Smith said.

"If you don't have access to nutritious foods or just stable access to food, that has an impact on your body's ability to fight off infection and to really be healthy and well," Smith said.

One of the things researchers don't yet know, Smith said, is what the study's data will look like at scale for our children as they return to school and interact more with members of the community.