Caption

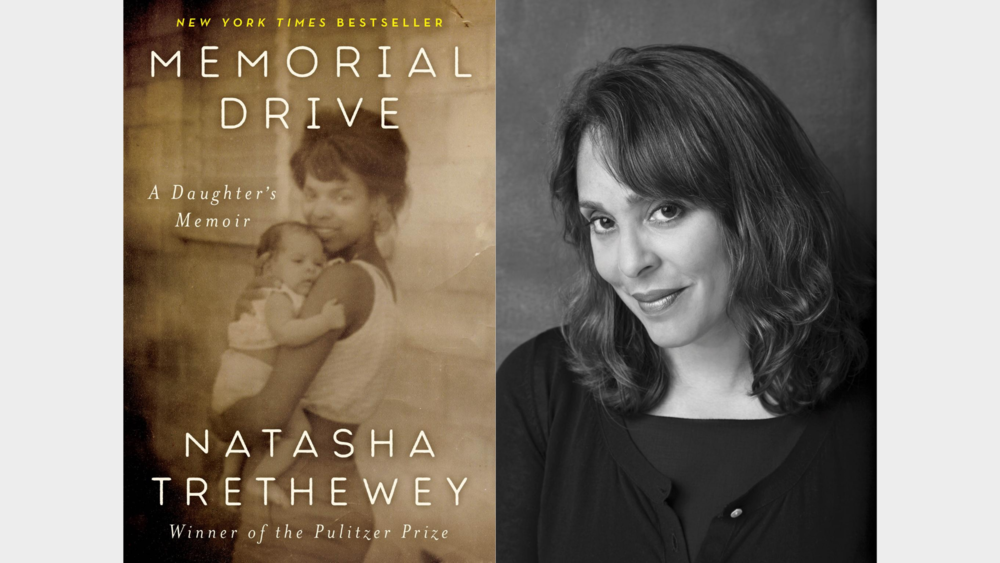

35 years after her mother was murdered by her ex-stepfather, Natasha Trethewey confronts the past in her new memoir, "Memorial Drive."

"On Second Thought" host Virginia Prescott speaks with Natasha Trethewey.

35 years after her mother was murdered by her ex-stepfather, Natasha Trethewey confronts the past in her new memoir, "Memorial Drive."

Natasha Trethewey was just 19 when her mother was murdered by her ex-husband in the Atlanta suburb of Pine Lake in 1985.

After decades spent willing herself to forget that horror, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author and former U.S. Poet Laureate confronts her anguish in a new memoir, Memorial Drive. The book is named for the street where Trethewey and her mother and brother lived after escaping the abusive home of her former stepfather — and where he killed her.

It was the deeper wound of losing my mother that really made me a poet.

On Second Thought host Virginia Prescott spoke with Trethewey in a virtual event co-sponsored by the Atlanta History Center and Air Serenbe. They discuss Trethewey’s journey – emotionally and artistically – as she confronted her past traumas.

"On Second Thought" host Virginia Prescott in conversation with former U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

On why Trethewey chose to write a portion of her memoir in the second person

There is the way that a feeling of trauma can fragment the self, can make you wish that you were someone else, and not the person to whom these things were happening. As an issue of writing — as an issue of craft — I wanted to show the way that trauma can divide the self. Because it became important to also show how — what happens in the next chapter — the way that that fragmented self is collected, is gathered, is composed through the possibility of writing, of telling a story.

And I try to set that imagery up in the very beginning of the book, in the prologue, when I write about seeing a news story in which the film shows me arriving and going up and walking into the apartment the morning after my mother's death. The "twoness" of that — feeling divided as the person watching oneself.

On what Trethewey learned about her ex-stepfather's plan to kill her

It was the week that we left, that we escaped. And my mother went to a shelter for battered women with my brother, and I went to stay with friends from school. And so he couldn't find her, but he knew where I would be: at the high school football game, down on the track with the rest of the cheerleaders. And so his plan was to come to the game and to kill me — to punish her. He didn't, he later told a psychologist, because I smiled and waved at him.

On why Trethewey decided to include court documents in her memoir, including a transcript from a call between her mother and her ex-stepfather

That was a very hard decision to make because, on the one hand, you think when you're writing a memoir that you're supposed to be telling the whole story. And I'm always interested, even as a poet, in documentary evidence. I make use of it all the time. And I thought that there might be readers who wondered why I wasn't telling the story.

And I thought about how I could tell you how wonderful, and resilient, and smart, and stoic and patient my mother was. Then you might just think, "Well, that's just a daughter who would make a heroine of her mother and say that anyway."

I needed you to see it. I needed you to hear it in her own voice, in her own words. Because then, I think, the facts are incontrovertible. You see just how much she had to do to try to save her life. And you hear her voice in ways that I could not ventriloquize.

On the factors that shaped Trethewey as a poet

Art heals us. It carries us. It helps us shelter.

When I think about the two things that probably hurt me — one of them has everything to do with being in Mississippi, being born to a place like that, when my parents marriage was illegal, when I was rendered illegitimate in the eyes of the law. Sort of the way that, in W.H. Auden's memorial to William Butler Yeats, he writes, "Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry." Mad Mississippi did some of that, too. And that's the kind of poetry I wrote as a child.

But it was the deeper wound of losing my mother that really made me a poet. Needing to try to contend with that grief that seemed insurmountable. Even if I'm writing about some of the most traumatic things, when I am creative and making a poem, that is when I'm at my happiest.

A poem is generative. It is the greatest act of hope there is in the face of despair. Writing a poem — and even writing this memoir — says, "I'm still here. I have survived this. And I can shape it into something beautiful." That is a wonderful feeling. Art heals us. It carries us. It helps us shelter.

Get in touch with us.

Twitter: @OSTTalk

Facebook: OnSecondThought

Email: OnSecondThought@gpb.org

Phone: 404-500-9457