Section Branding

Header Content

Amid Movement For Racial Justice, The Need For Rebellious Art — And Uncomfortable Conversations

Primary Content

Today, in celebration of Juneteenth, Power Haus Creative has organized what they’re calling the “Juneteenth Takeover” – in which 19 Atlanta artists will display their work on the exterior of the historic Flatiron building in downtown Atlanta.

Carlton Mackey and Melissa Alexander are two of those artists.

"On Second Thought" host Virginia Prescott speaks with Carlton Mackey and Melissa Alexander.

Mackey is creator of Black Men Smile and Beautiful in Every Shade and director of the Ethics and The Arts Program at the Emory University Center for Ethics. He and Atlanta-based photographer and filmmaker Melissa Alexander (also known as “Phyllis Iller”) joined On Second Thought to share how they are approaching the expanse of art, representation and symbolism at this pivotal time of reckoning with racial inequality and violence.

Both artists say that their work aims to highlight experiences of Black people living in joy and freedom – both as a means of telling the stories of their communities as they see them, and to counter the existing narratives of Black communities in media and news at large.

“You have all these different things that are going around in the news about us – but that's not my story,” Alexander explained. “And I didn't want anyone to minimize us to just Black death – because there's also Black joy. There's also Black life. There's also Black love. There's also Black pain. You know, we're a myriad of things.”

Alexander cited the photography of Kwame Brathwaite as a profound inspiration for her own work. Brathwaite was a pioneer of the “Black is Beautiful” movement in the 1960s, which fueled a celebration of African American style and identity.

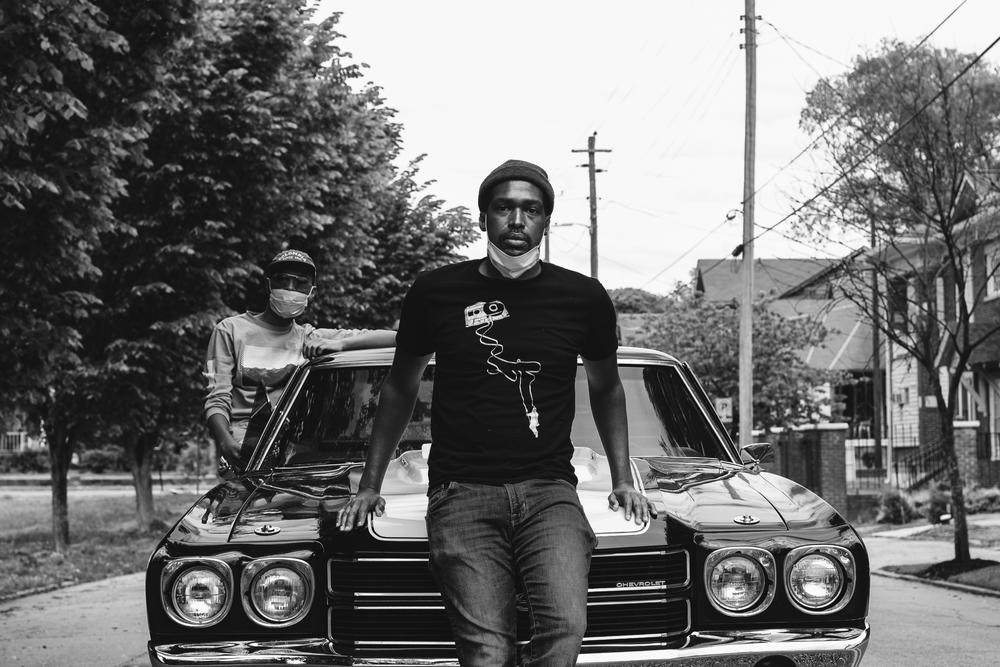

Alexander’s own work, a recent series of social distancing photographs called “Pull-Up Portraits,” was recently profiled in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Mackey noted that his own art is an act of resistance – to display “what we look like on the other side of the struggle” – and that it is intimately tied to the work that needs to be done right now amid the movement for racial justice.

This work, Mackey says, has different paths and functions for different people. While Black people focus on their grief, mental health, and building up images of strength, beauty and resilience, White people have a different task at hand: educating themselves about the depths of systemic racism, and having uncomfortable conversations with each other.

“I've spent a considerable amount of time wondering if the effort that I'm putting into loving myself and working to maintain my sanity in this particular moment in history, if the effort that I'm putting into that is equal to the effort of the people who reap benefits from the system to work to dismantle it, or to dismantle in their mind the very bricks that built the systems,” he said.

Both Mackey and Alexander discuss how art and symbolism aid in the journey, but over the course of this half-hour conversation, the discussion also delves into uncomfortable questions regarding the insidiousness of racism — and the sincerity of white people to dismantle a system that has benefited them.

“In order to move forward with some real progress, you’ve got to get to the nitty-gritty,” Alexander said. “You’ve got to get down into it. You have to dive into those places that you don't want to accept. The time for ignorance has passed.”

Listen to the full discussion between Alexander, Mackey and On Second Thought host Virginia Prescott – which explores how art can serve as a form of resistance, as well as the importance of conversations about race and systemic racism – using the audio player embedded in this article.

The Juneteenth Takeover exhibition will be on display from Friday, June 19 through Monday, June 22.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

On the role of the artist, particularly during this moment and movement for racial justice

Mackey: I like to say that the role of the artist is to translate the longings of the hearts of the people. And that is how, in my own reflections, I've worked to think about the weight of what this moment means and my function as an artist. People lean on us to represent them. We have a unique responsibility and role to proclaim the expressed desires, to channel the righteous rage of the community that we are part of – the wellspring from which our art comes. But even more importantly, because art is so important, the transformation is in showing us what we look like on the other side of the struggle. And to give us a vision of what it might look like if we weren't simply downtrodden, if we weren't simply in this state of crisis. And I think one of the beautiful things that I've seen happening and that I want to be a part of is showing a vision of our strength, of our power, of our resilience, of our beauty – as a reminder that that which they say we are is not the final word.

On Alexander’s inspiration to make a series of social distancing portraits

Alexander: It came to me when a friend of mine, Olamma, came to my house. This is right after, you know, they had put the mandate out that we were supposed to be social distancing. And I had been feeling the effects of social distancing. I'm not necessarily the most touchy-feely person. There was a moment where I realized that all I wanted was a hug. Right? And understanding the power of a hug. It further revealed just how quickly we go from being with each other to being alone. And how many people were feeling alone at that moment. So when Olamma reached out to me, it was like, “I just need to see you. I'll stay in my car. You can stay on the sidewalk and we'll visit in that way.” It's still six feet, right? So, as she stood there in front of my house, in her car – she eventually got out – her son was on the rooftop, I was looking at them and I thought, “How amazing would it be just to capture this moment, to remember this moment?” It was just so surreal, but the light was coming in very beautifully, so I was like, "Hold on a second." I ran in my house. And as I was opening the door back to come out to take their photo, I thought "Pull-Up Portraits," right? This is a way for, or it has served as a way for us to remain connected, to always know that your feelings are valid. You are seen. You are appreciated. And it just became a thing. But, again, it was because I wanted to be there for that. I wanted to capture that.

On a coordinated effort to simultaneously uplift Black people while dismantling systemic racism

Mackey: I think that there are two conversations that are being had or that are necessary. There is a vital and important role for the architects of this American system and the architects of racism to have conversations about all of those things that are painful, maybe even for the first time – for that pain to be transferred into maybe education, into courage, into modeling a form of, if not at least solidarity, a basic baseline education which has been woefully ignored. So those things need to happen. There is a place and a function for them, and I think there is a place and a function for them primarily for White people. I think that there is a place and a function for another form of a revolutionary act, and it is radical acts of self-care, radical acts of love by Black people, among Black people, on Black people, to counter the epic amount of violence and misrepresentation and oppression that we are both seeing but have been experiencing for hundreds of years. I've spent a considerable amount of time wondering if the effort that I'm putting into loving myself and working to maintain my sanity in this particular moment in history, if the effort that I'm putting into that is equal to the effort of the people who reap benefits from the system to work to dismantle it or to dismantle in their mind the very bricks that built the systems. And I am working hard to live and to flourish and to thrive. And I hope that you are working hard to understand why I'm in this position.

On how Mackey sees his work as a form of rebellion and resistance

Mackey: So much of my body of work is about offering myself and my community reflections of ourself as beautiful and as strong. But when people go and they Google me and they see my work and they see Black Men Smile and they see all these reflections: you cannot miss that that is an act of resistance. That is no more important than, but no less important than the radical acts of resistance that we're seeing in the streets, the radical calls for change. The expressions of joy that you see me embody are not detached from the real-life experiences of something that looks totally different than the images that I'm putting into the universe. But don't get it messed up. Don't get it twisted. Do not think that we're just around here smiling and happy. And do not think that we are doing any of those things with you in mind, or to decrease the discomfort that is being experienced by people who are collectively either confused, or feeling guilty, or not knowing what to do with us seizing this moment to make demands and to make these proclamations. And that we can no longer and we will no longer wait. This is a moment for all of us to seize, to capitalize on. And whatever it looks like, whether it is a radical restructuring of the way you live life, of your relationships, of being with partners who are racists and that you've accepted, of being a part of organizations that you have an influence within, but that you've accepted the excuses for why it's not quite the time. This is the time. It is both the time to dismantle and it is the time to build. And that is the stretch. That is the movement toward which we will be able to obtain and to make sustainable beyond this moment.

On communicating important experiences over sensational ones

Alexander: Being a storyteller and being someone who enjoys hearing stories, with this Juneteenth Takeover that we're going to be doing, I struggled internally with what images I would offer. I know that the more sensational is the fist in the air, right? The more sensational – I guess, what people would want to see now is the person that's running in front of the burning building, you know, that has been set on fire. The marching, all of that. Instead, I listened to myself and I offered photos of a Black man kissing his baby. Because that, to me, is the experience I know. That, to me, is a reminder of who we are. When you're pushed into a corner for hundreds of years? Yeah, Black rage is real. It's going to come out, and it's going to come out in volatile ways. It's not going to be easy. Gil Scott-Heron said, “The revolution will be no rerun. The revolution will be live.” This is what we’re experiencing right now. For years we have been trying to explain that we are people. We have communities. We have love. We have blood running through our veins. How long do we have to beg to be seen as something other than three-fifths of a human? I'm tired of trying to prove our worth. And because I think there have been generations of trying to prove that worth to other people that I seek to remind us of who we are.

On the responsibility of White people to educate themselves and have uncomfortable conversations about race

Alexander: People love painting America as this kumbaya and it's anything but. In order to move forward with some real progress, you’ve got to get to the nitty-gritty. You’ve got to get down into it. You have to dive into those places that you don't want to accept. [...] It's okay to say, "You know what? I haven't been around a lot of Black people, so I don't completely trust them. I don't completely understand. I can only go off of what I've seen on TV and all of these things." It's okay to say that because you're admitting something. But to just outright not care and to not try to do something? The time for ignorance has passed. How many times does someone need to die or be murdered brutally? Those last moments of George Floyd's life, he called out… he called out for his mother, who had already passed. He knew he was going to die. For something as simple as a counterfeit bill. It brings to mind the lynching museum in Alabama. And you read the reasons why those Black people were killed: for not walking across the street properly or looking – looking – at someone, quote unquote, the wrong way… lynched. Killed, burned, murdered. Whole families are dead. I don't have space in myself, I'm not going to say forgive, but we never forget. Right? We never forget. That is the legacy that America has built. And it's not something that we can sweep under the rug. However, moving forward, I'm very hopeful that we can be together – that we acknowledge it, but that doesn't mean that we have to continue the legacy forward.

On the power of expressing liberation in both art and life

Mackey: I've been exploring this idea around how much symbolism was involved in the things that we're talking about […] – the horrific images that we've seen and the work that must go into imagining oneself as something other than that. I think that what Black people can do, and what the work of Melissa is doing and what the work that I'm trying to put out there is doing is centering the Black narrative and Black joy so that Black people can accept for themselves their own freedom. So that everyone around me, that comes in contact with me or my art, in their own form of marginalization and oppression – as women, as gay folk, as people who are other-abled, as people who are brown, as people who are immigrant – can celebrate the sound of hearing their chains fall onto the ground by engaging with me in my work. That is the power of the Black voice right now, particularly right now. I think that if I can embody my liberation […] and claim it as my own and live it and express it and show it and show up as it, you can't help but want some of it. And what I'm going to commit to for Black people is to see me and to see my work and to see themselves as already there, as already free, as not waiting on the laws to pass, not waiting on White folk to watch the movies, not waiting on the companies to do whatever. But this Black man is already living and expressing himself fully as who he knows that he is. And you, as a woman, you can't help but know that yours is possible. Because if I can do and be that right now, what are you waiting for for claiming your own? That is what and who I want to be and it is what I'm committing to. And it is what I want my people to commit to and to live and to embody.

Alexander: Yes. Yes. Just… how do you undo so many years? How do you forget so many years? And time and time again, rise. We've known that Black Lives Matter. And so we stand in that fully. We stand in that fully.

Get in touch with us.

Twitter: @OSTTalk

Facebook: OnSecondThought

Email: OnSecondThought@gpb.org

Phone: 404-500-9457