Section Branding

Header Content

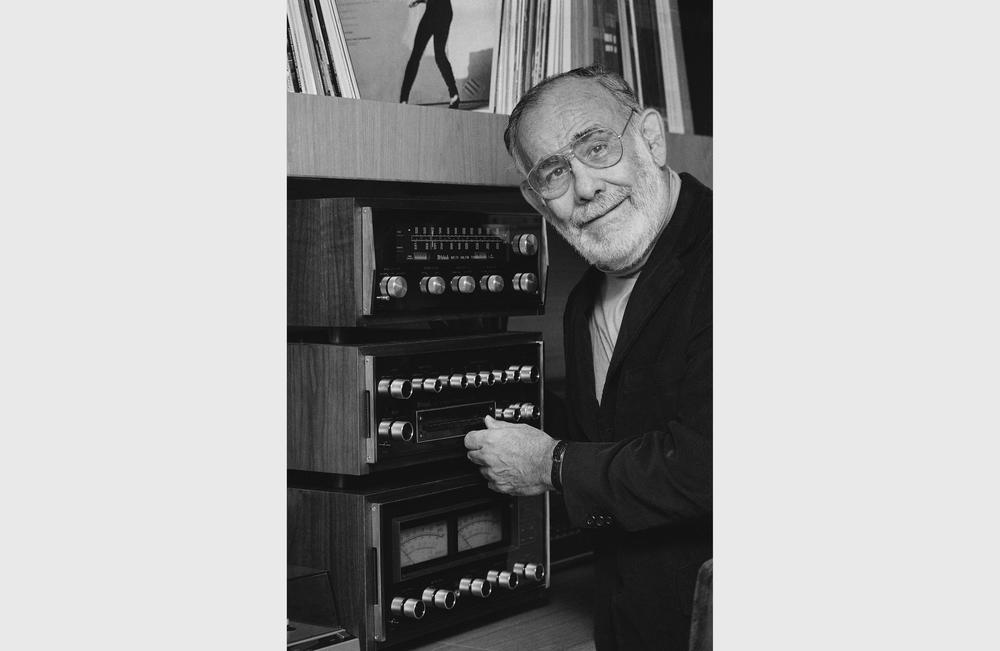

From Ray Charles To Aretha Franklin, How Legendary Producer Jerry Wexler Shaped Soul and R&B

Primary Content

For decades, "race music" was the euphemism used for recordings by African American musicians. That didn't sit well for a young music journalist named Jerry Wexler, who coined the term "rhythm and blues" in 1949. The term stuck.

But it was as an executive and producer at Atlantic Records that Wexler changed American music. He introduced the masses to Ray Charles and Big Joe Turner, and honed the sound of Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding and Wilson Pickett.

"On Second Thought" host Virginia Prescott speaks with Joe Alterman.

On Saturday, Mar. 14, ATL Collective and the Atlanta Jewish Music Festival will "relive the soul" of the legendary music producer.

The event will touch on Wexler's storied career and his influence on popular music. It will also include performances of songs that he produced, or were released by Atlantic in that era, including music by Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, Bob Dylan, Booker T. & the M.G.'s, Led Zeppelin, Professor Longhair, and many more.

Joe Alterman, executive director of the Atlanta Jewish Music Festival, joined On Second Thought to share insight on Wexler, one of the few non-musicians inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

"I think [Wexler] really represents a producer that wasn't out to accomplish his objectives for the music," Alterman said. "He was trying to figure out what made these artists special and do whatever he could to bring them out."

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

On how Wexler got into the music business

After he said he, quote, “endured the obligatory bar mitzvah” — which I like — then he went to the army. And when he came back, he didn't have work, and he was just hanging out in jazz clubs. He was a big jazz fan. He was a real intelligent listener and loved the music. And basically, he got a job at Billboard magazine. And he got lucky getting that job because, in the interview, the guy asked him, you know, the obvious question of that era, which is, “What record label is Nat King Cole on?” And he didn't know. Somehow he still got the job. But he was writing for Billboard, and then he ended up taking over the publishing estate for Frank Loesser, who wrote 'Guys and Dolls.' And then two of his friends whom he met hanging in these jazz clubs, Ahmet Ertegun and Herb Abramson, who ran Atlantic Records, asked him to take over the publishing for Atlantic. But he said he didn't want to work for friends. So they asked, “What would you want to do?” And he said, “I want to be a partner.”

On Jerry Wexler’s work with Ray Charles

You know, the lesson here to me is the “less is more” thing. And I think Jerry just really understood what made Ray [Charles] special and how to encourage his career as a producer. For example, he wrote in his book, “Even on a bill with a host of other powerful performers, Ray Charles bears special distinction. Of all the artists I've worked with, only three rate the Appalachian genius, and he was the first.” And Aretha and Dylan are the other two, by the way. But I think he really just understood how to work with him. He didn't overproduce him. He actually said that, “I realized the best thing I could do with Ray was leave him alone. He needed a producer like Ray Kroc needed a hamburger.”

On the impact of recording music in the South

Jerry Wexler became taken with the town Muscle Shoals, and he ended up bringing a lot of his artists to record there. And I think for many of the artists, they've spoken about how [...] it was getting out of the city, and it was relaxing and which definitely aided in the music. But everyone really speaks of this like kind of a vibe in the air, that was kind of a spiritual thing that made them feel the music in a deeper way. So when they were there in Muscle Shoals recording at Fame Studios, Jerry spoke about the magic there.

On Wexler’s influence on Aretha Franklin’s sound

I really think he helped her find herself. Because if you listen to her on Columbia before she came to Atlantic, it's great stuff, but she's singing standards and it's not quite an Ella Fitzgerald knockoff, but it's more in that vein. And actually, when she came to Atlantic Records for her audition, Jerry told her — in the audition — to, quote, “drop the Judy Garland Cabaret Act.” And then he found out that she played the piano in church, so he told her to sit at the piano and play. And that kind of changed, you know, everything. It wasn't that he had to push her into this southern soul thing; it's that Columbia really didn't understand her gospel roots. And he kind of saw something in her that maybe she didn't see quite yet, and he really helped her get to it, I think.

On what made Wexler such a talented producer

Well, I think, you know, reading his autobiography and becoming familiar with his story, it's just so apparent not just how much he loved the music, but how knowledgeable he was about the music and how that really worked in favor of producing these artists. For example, with Ray Charles, he really understood what those horn arrangements were about. They were kind of emulating Ray's comping on the piano. They were kind of George Shearing chord voicings. You know, he really got it. And I think he really represents a producer that, you know, wasn't out to accomplish his objectives for the music. He was trying to figure out what made these artists special and do whatever he could to bring them out. He always said, “Let Aretha be Aretha.”

Get in touch with us.

Twitter: @OSTTalk

Facebook: OnSecondThought

Email: OnSecondThought@gpb.org

Phone: 404-500-9457