Section Branding

Header Content

Shots In The Back (Bonus): Telling The Story

Primary Content

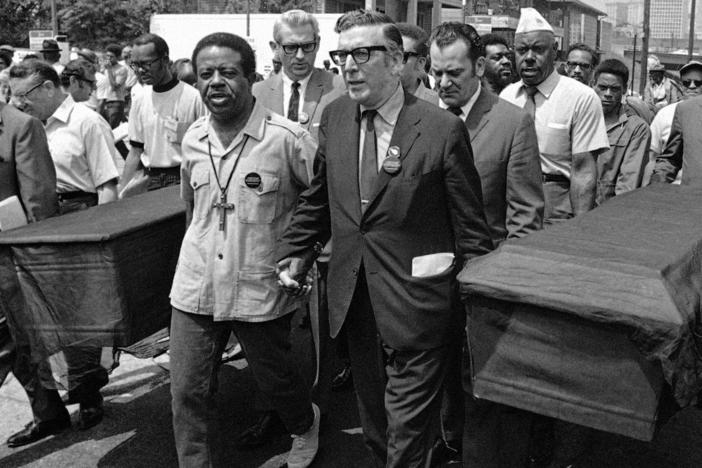

Host Sea Stachura and editor Keocia Howard look back on the making of "Shots in the Back: Exhuming the 1970 Augusta Riot."

TRANSCRIPT:

Sea Stachura (STUDIO): Hey there, it's Sea Stachura, host of Shots in the Back: Exhuming the 1970 Augusta Riot. Since we released the first episode of the show, listeners have been asking questions. Some people have had questions about public policy. Others asked about how we did what we did. Trial and error is the answer. None of us had previously made a documentary podcast about racism and history, and I personally knew I had some blind spots as a white woman. So my Black colleagues and connections were integral to the success of this podcast. And that includes our editor, Keocia Howard. She and I caught up recently in a live virtual panel about the show. And one of my questions for Keocia was about being a Black news editor. She is one of the very few out there.

Sea Stachura (LIVE EVENT): This was a really — this is a personal and sensitive topic for you. And so how was it for you editing a white journalist as a Black female journalist?

Keocia Howard: It wasn't what I was expecting it to be. And so I certainly was — was glad. I was happy that you had done the work. I was happy that you had not tried to insert yourself into the story. You just wanted to tell the story. And, you know, you were open the entire time. You were constantly checking yourself. You were constantly saying, "You know, I don't want to say this wrong." Or, "Do you think that this might step on some people's toes?" You are very self-aware — like you are very aware of your whiteness in a way that allowed you to kind of step aside and be open to — to suggestions and to be open to the editing process. And so I certainly enjoyed that. I think also, for me, this gave me an opportunity to lean into what I believe about racism in this country and my belief that Black people are not going to be the solution to the issue of racism. It is going to take white people, white allies, who also are championing the issue, who are also telling these stories. And so, whereas in the beginning, I was a little apprehensive because I didn't know you, didn't know, you know, what your background really was and what you had done. And so I was kind of like, "Ehhh, I don't know." But for me, this was a huge win because I think that you really had a heart for it. And I think that that shows in the work.

Sea Stachura: It is something that, you know, having done projects on, you know, back in 2013, I did a couple of public events about the research that I was doing when I was teaching it at Augusta University, which was then Augusta State University. And I — I have looked back at some of that material and realized that I just — it's not that I didn't have a sincere sincerity, but the depth of my knowledge was so limited. I'm really — I'm really proud of myself for stepping back, because I look at that and I'm like, you know, I kind of perpetuated some myths. I could have done a better job of not being a voyeur. Which is, I think, one of the one of the problems with white journalists covering issues about communities that are not their own, is that we can come in and — and — and say, "Oh my gosh, look at all this stuff." And I definitely was afraid that that was, you know, that there were elements of that. So I'm, yeah. I'm so glad that you were — you were my editor and that you were it and that we were able to — to, you know, some together and feel like we had a good, trusting relationship was one of the things that you've said to me over time is that this has been — this has been a really rewarding project for you. Can you speak a little bit more about that?

Keocia Howard: When I learned about this story, I was like, "Wait, why don't I know about this? Why don't people know about this? Like, why isn't this a thing?" And so to be able to help bring the story to light was just like, oh, man. Yeah. This is absolutely, like we got to do this. We got to make this happen. And so for me, it was partially just the education of it all. Just learning about the story. The stories themselves. But this was also like getting into the meat of everything. Listening to those interviews, like all the great sounds, listening to people like Claude Harris.

Claude Harris: So our whole aim and intention was, "Let's make change. Here's an opportunity." But the whole intention was, "Don't hurt anybody."

Keocia Howard: It was just eye-opening for me in a way that you don't get, you know, especially on the editing side of it, because, you know, unfortunately, everything doesn't make it into the podcast. So there are some things that I got to hear, like just behind the scenes that I'm just like, wow, you just look at life differently after working on a project like this.

Sea Stachura: Yeah. I think you'll feel pretty good about this. We heard from people like Claude Harris. But we also heard from Sgt. Louis Dinkins. He was implicated — implicated himself in three of the shootings that took place and was put on trial but acquitted for the shooting of Louis Nelson Williams. Why don't we play the clip from Dinkins now just to remind us all of who he was and what he sounded like?

Louis Dinkins: I turned, with the gun on my body, positioned still on my hip. I touched off that head trigger and I got him right through the knees. Or knee, I should say. When those shots hit him, I knew I hit him in the knee because I could actually see red streaks. Anyway, they finally got him in the back seat and he’s bleeding like a slaughtered hog.

Keocia Howard: Me and Louis, we — oh my god. Editing the podcast with Sea — Like, I was hearing all of his little statements and I was like, "Oh, my God. This man." Like, OK, I get it. During a certain time, there was a certain way that people thought about Black people. And as a police officer, yadda, yadda, yadda, blah, blah, blah, right? But all these years later, to hear him tell the stories again with no remorse, with no type of compassion in his heart or anything that was like, you know, "I feel bad" or even, like, "Maybe it was a little bit wrong." Like there was just nothing there that said, you know, "These people are human." And so I even wonder, oftentimes, Sea: If it wasn't you doing the interview, like if I was there, would he even regard me with any level of respect or like — you know, or would he just treat me like "I'm not even talking to you?" Because that's just the way that he came off, like still. And I can't say "still" because I know he's passed on. But at that time, for it to be, you know, so many years after the right for him to still speak in that manner. I mean, it just disgusted me. I really — and listening to him, there were so many things where I was like, "Oh, this is terrible. But we got to put it in there. We have to make sure that people hear this because this was really the heart and mind of someone who was involved." And so as — as hurtful as it was to hear those things, it was also very necessary for him to be a part of the story. And it was also very necessary for people to hear what he had to say, because, you know, I can hear that in the mind of a police officer now who kneels on somebody's neck for 10, 11 minutes. I can hear that now in the mind of a police officer who shoots someone because they're running away. Like, it just all — it’s very real. And it's just the reminder that, you know, those mindsets don't go away. Over. OK, and let me not say those mindsets don't go away, because I do believe that people have the capacity for change. But it's not an easy change and it's not an automatic change. It is an intentional change that people have to want to make and that people have to work to make. And it's obvious from hearing Louis Dinkins all these years later that he was not one of those people.

Sea Stachura: Yeah, I think you're right that he — he would have given different answers to you and he may not even have been willing to give you the time of day because of how deeply that racism ran. When I — when I started interviewing him, I was doing oral history interviews. And so that gave me a little more leeway to let people tell the story that they wanted to tell. But sitting across from that much casual racism and hatred, I definitely felt just guilty that I wasn't calling him on that stuff. And what I came to was that, by letting him speak and letting him assume what he wanted to assume about me, he was speaking his mind, and that was better for the story, just as — as you said. I think he may have used this event as like his war story. And that Black people in this event were his enemy. So I just kept asking for more. And I was hopeful that underneath the hubris and the condescension and just hostility that — that there was perhaps an indication that this was a cover for something that had deeply hurt his heart. You know, in the way that some people kind of feign bravado when — when they're actually scared. And so we just, you know, on that last little point, that was me being hopeful that — that white racism wasn't as embedded. That it wasn't — that it wasn't so pervasive that — that if I just dug a few layers deep, you know, you would it would be scraped away. And I don't want to say that I've ever thought that white supremacy and racism is shallow, but it just reminded me that these are very entrenched ideas, which, again, goes back to basically what you were saying, Keocia. We talked in Episode 6 to the Lincoln County teacher, Christie Bryan. And one of the things that she said was she knew about this, vaguely. She had heard from her mother that downtown had burned but didn't know what had happened or why anything had happened, which is very, very common for people. The narrative at that time, as the news media was writing it and as what leadership was spreading it, was, you know, “Dumb people did something stupid” and that was the end of it. So she was really thrilled to be able to put some depth to that event and understand what really happened. And she also talked about how she was intending to incorporate this into her Georgia studies class in the future. And I know, actually, that a few teachers in Richmond County schools will also be doing that. And that's great and all, but one of things that she said was just that the teachers around her weren't comfortable with this history. They were actually afraid to speak about it at all. And so I just want to — I want us to listen to one of her comments.

Christie Bryan: I believe a lot of teachers are afraid that they might lose their jobs. As someone was saying to me last night, "We walk such a fine line." And it's really difficult to pacify everybody and even though it's facts, this happened, a lot of people are like, "Why do you want to bring that up? Why do you want to stir up trouble?"

Sea Stachura: I find that question, “Why do you want to stir up trouble?” interesting, because on the one hand, we're more than willing to talk about World War II. But on the other hand, we're not as willing to — or some of us are — not as willing to talk about the civil rights uprisings, something that the teacher said with, you know, that it's hard to pacify everybody.

Keocia Howard: And I think that, you know, that — that mindset, that mentality is exactly the problem is that we've got to stop trying to pacify everybody. Just like, you know, John Lewis said, "Good trouble." Like we can get into some good trouble. Like there's a reason that we should be waving a flag for certain issues. There's a reason why we should be putting our fists in the air for certain issues. There's a reason why we should put up a sign that says Black Lives Matter. And that we should be able to stand firm in the decision to do those things without feeling shameful because of what our neighbor might think. You know, quite frankly, I would be looking at my neighbor like, well, you should feel shameful that you're not doing something, right? And so I think that the mindset has got to change from trying to pacify people and trying to meet the needs of everybody. Guess what? It doesn't matter what your position is, somebody is going to have something to say about what you said. So you've got to figure out what is your conviction? What is the thing that you're willing to stand behind and stand behind it? I was on Twitter the other day and a woman posted one of the questions that her child got in like a test because, you know, everybody's doing school from home. And the question was like “the Civil War hero rode up on his valiant steed…” And she — you know, and she was a white woman — she posted it. And like mentioned the company that made the test and was like, "What is this racist propaganda that you’re teaching my child? We will not." And like, the company came back and they were like, "Oh, we're so sorry, we're going to re-evaluate our tests." But I mean, even now, like even in the middle of everything that's going on, you have to pay attention because, I mean, it's not in the curriculum. The curriculum is not telling the full story. And so for me, as a parent, I have a weight on my shoulder to make sure that I'm teaching my child certain things, like my daughter will know the story of the Augusta Riot and Charles Oatman because, well, for one, she’s like "Miss Sea is your best friend now because you talking to her every day for like three straight months," but also because, like, I'm like, "OK, this is a story you need to be aware of, so we're gonna sit down and we're gonna have some of these tough conversations." And so hopefully more parents will start to take that initiative as well to say, hey, this is not being taught in school or that thing needs to be. There also needs to be some light shed on the other side of this story. And hopefully people can really start to teach our children, you know, so that they're not looking at the world through rose-colored glasses and thinking it's all unicorns and rainbows. But the other thing — talking about, you know, if you shoot somebody in the back while they're running away, that's not like — there’s no way to look at that as being good. But the painful reality of that time is that it was actually okay for police officers to shoot someone in the back. It was okay as long as the officer was able to say, oh, well, I caught this person doing a crime. The law actually said that they could shoot somebody in the back. And so I have kind of a morbid joke that my friends and I say, which is that we're only one law away from The Handmaid's Tale. We're one law away from some crazy turn of events that would allow for terrible things to be done to people, you know, because at one time, slavery was the law of the land. At one time, Black people were seen as three-fifths of a person. At one time, a police officer was allowed to shoot somebody in the back as long as he said “Well, that person did a crime.” And so I think we also have to be careful about, you know, the idea that, oh, no, that's wrong. That's terrible. Well, if the law says it's OK, somebody can get away with it. And if somebody who’s a really smart and really good lawyer can find X statute and Y code somewhere in the — in a book, they can argue for why it's OK for that police officer to have done what he did. And, quite frankly, why I think there are several officers who are sitting at home with their families right now when they probably should be in jail.

Sea Stachura: There are journalists who won't say that we live in a white supremacist society. Because that, to many, is not a fact. But when you define white supremacy and then look at the research that backs up all of the ways in which Black people are subjugated, there's no doubt. And I found myself hesitant to use that term because I was like, oh, I hear that little voice in the back of my head. There are people who are going to be like, well, this just shows that you're liberal. This just shows that you are not being an objective journalist. And we've — we've done that in journalism with climate change. We call it climate change now instead of global warming, right? And that is to appease people who aren't even sure that it's scientifically valid. I don't want to get myself in trouble here, but it was, I think, a challenge to turn that off. To turn off that attempt to make everybody feel like they came out as a good guy in the end. So our time is coming to a close. We do have a few kinda miscellaneous questions that I want to get to that our listeners have asked. And Keocia, I think you have a couple of those.

Keocia Howard: Yep, I have them. So I'll jump right in with the first one. It is — yeah, I want to know this, too — what statute or policy was it that paid Black students to study outside of Georgia?

Sea Stachura: All right. I have never found the exact statute. I have found several people who benefited from it. This — it's also listed in the Georgia Encyclopedia, which is run by the Georgia Humanities Council and the Georgia Historical Society. And what they say is that this was a common practice and it was — it wasn't until about '60 that the federal courts essentially banned states from doing this. 1962, if I remember correctly, is when we first — we see the first Black students attending University of Georgia. But there were only two for a really long time, so I'd be curious to know if that practice somehow continued.

Keocia Howard: That's a good point. Another question: The Richmond County jail — was it as bad as described in the show?

Sea Stachura: Most definitely. By the mid 1960s, a grand jury had taken a review of the facility and said it was inhumane and unsalvageable. And they made a demand that the building be replaced. Now, I don't know the details of that well enough to know whether that came with a fiat that just kept getting extended. But I do know that it was into the '70s that they were still using that prison. That jail. And I actually got a letter from a person who's an inmate over in the Atlanta area who said that he had lived in the Richmond County jail on Fourth Street in the late '70s and it was exactly as described. The year that that grand jury came, came to its conclusion is it's like 1964, is what's coming to mind.

Keocia Howard: Who did you intend for the podcast audience to be?

Sea Stachura: When I wrote the first episode, this was before Keocia came onboard. I wrote it and then I looked at it myself and — and I realized that I was speaking pretty much exclusively to white people. And so, you know, I have talked about this before. I then brought it to a friend of mine and she's Black and she was like, "OK, you're using way too many — like, look at all of the white voices that you've put here." And I was like, "Oh, but I just want to use archival tape." And she was like, "Yeah, but you're prioritizing the voices of people who didn't speak to any Black person about why this happened or what was happening. Just a lot of white officials who said, 'Well, I think some outsiders came in.'" So I think you and I, Keocia, have had a couple conversations about how the public radio audience is primarily white and primarily older. And so I wanted that to be accessible for that audience. But I also wanted it to speak to a much broader audience, to people of color who — My understanding is that there's a lot of times when we journalists or mass media — mass news media in general — is telling a story as though — you know, it's Cinco de Mayo and we're doing a story about what is Cinco de Mayo. And that kind of a story is pinned directly toward white people, right? I mean, no one in the Hispanic community is asking that question. So, I think with your help, we — we made this into something that had enough code-switching for our white listeners, who are maybe not as informed on Black history, but not so much that it was a turn-off to Black listeners and other listeners of color. And, I don't know. It'd be terrible if you answered my question negatively. But I'm going to ask it. What do you think? Who do you think we — What do you think we did? And who do you think we were talking to?

Keocia Howard: Yeah, I'd have to agree with that assessment. I mean, I, I kind of toed this line myself on wanting to explain things to white people, but then also not wanting to shoulder the burden to be the person to have to explain it all. And also to have, you know, the clear understanding that I'm not the voice of all Black people, right? And so, you know, I think that we did a good job of balancing out the “OK, let me explain to you what this means,” and also just telling the story. I think the story itself (or the stories, because there are several stories within the larger story) but just let the stories breathe and tell themselves and tell themselves and let the people who were involved tell the story. And where there was the need for some bit of explanation, you know, we would add that in. But for me, I think we were effective because we allowed the narrative to happen. Just — it was very character-driven inasmuch as it was narrated and kind of explained. So, you know, I think we did a fabulous job.

Sea Stachura: My thanks to Shots in the Back editor Keocia Howard. And now it's up to you. What are you going to do to keep the story of the 1970 Augusta Uprising alive? So many of you have pointed out that this history mirrors the present, proving the adage that those who don't learn history are doomed to repeat it. So what will you take away from what you've learned? Many thanks to the rest of our team, Rosemary Scott, Jesse Nighswonger, Autumn Rose, Josephine Bennett, Don Smith, Grant Blankenship, Cheniqua Dickins, And Nefertiti Robinson. Our theme was composed by Tony Aaron music. Gary Denis is the Executive Director of Jessye Norman School of the Arts. Sean Powers is Georgia Public Broadcasting's Director of Podcasting. This podcast is funded in part by a South Arts grant. Please leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts and for show notes, visit GPB.org/Shots. Thank you for listening.

Host Sea Stachura and editor Keocia Howard look back on the making of "Shots in the Back: Exhuming the 1970 Augusta Riot."