Listen

Listening...

/

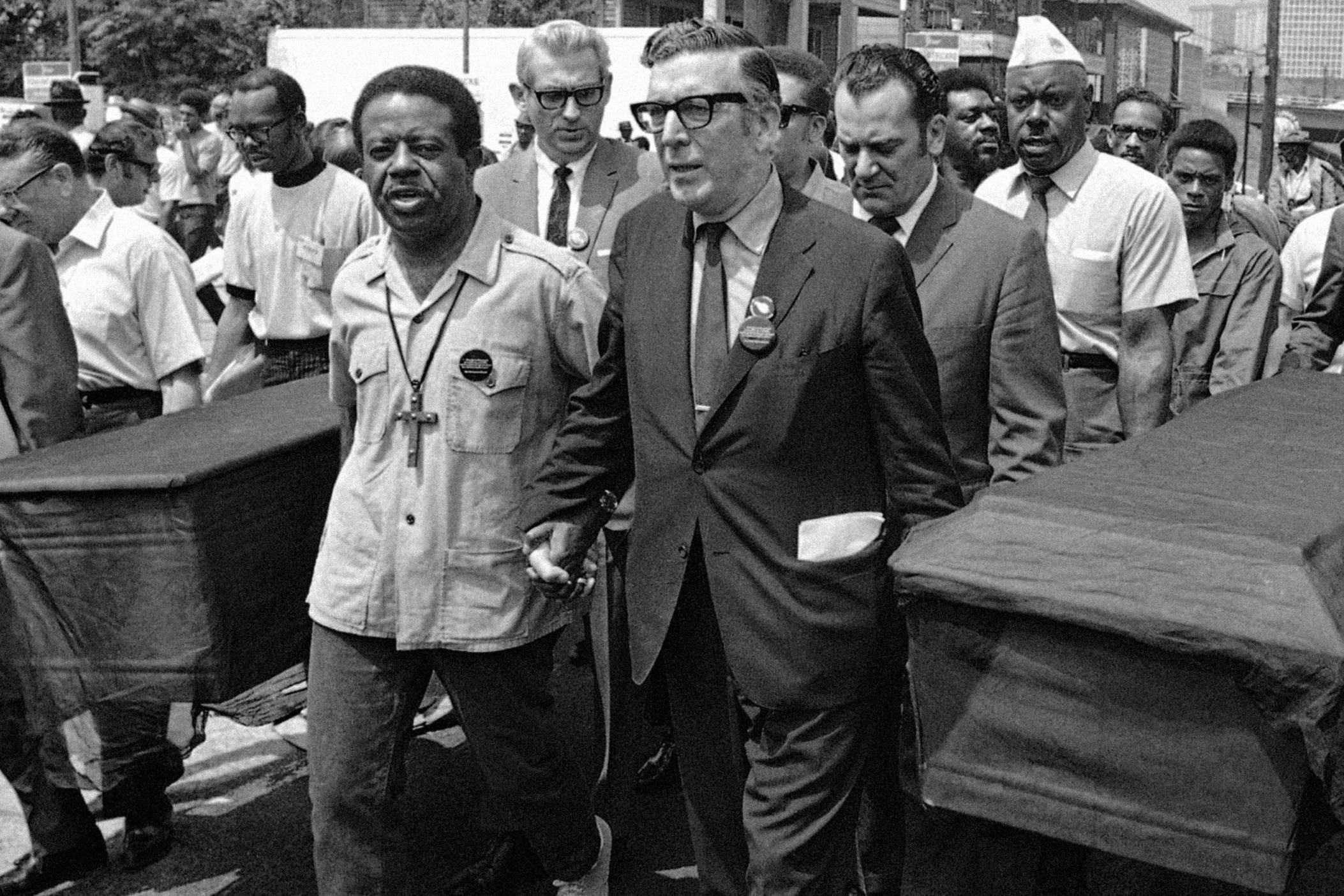

In the months following Augusta's riot, activism was at an all-time high. As white Augustans braced themselves for the possibility of more violence, Black activists worked for more immediate change. Meanwhile, the police department rewarded the officers involved in the riot, and the friends and families of "The Augusta Six" demanded justice.