Listen

Listening...

/

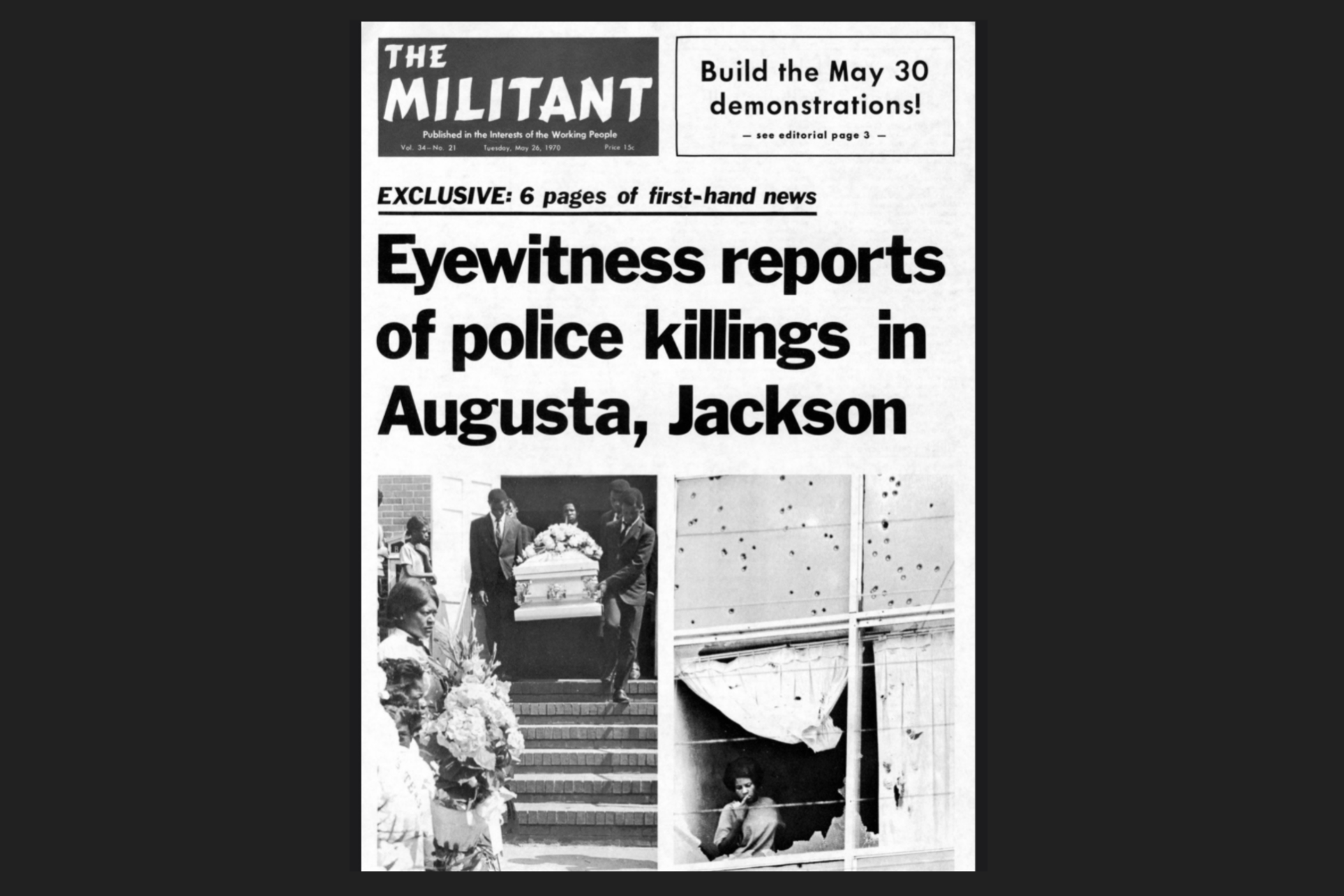

Inside the chaos of the uprising, Black and white leaders were trying to quell the violence. As rioters set fire to white-owned businesses, police officers were told to shoot to kill. In this episode, we tell the stories of the six Black men killed by white police officers. The victims, who were all shot in the back, would be remembered as The Augusta Six.