Section Branding

Header Content

Georgia's Deaf Community Seeks Accessibility In News And More Amid COVID-19

Primary Content

On Thursday, an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter was to appear in COVID-19 video briefings at the White House – a new first that was ordered by a federal judge.

For Jimmy Peterson, executive director of the Georgia Center for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, and Madison McNair, executive producer of Sign1News, this accessibility to news about a global pandemic means everything to the deaf and hard of hearing (HoH) community.

All 50 states’ governors provide an in-frame interpreter during COVID-19 briefings and closed captioning is widely available for TV news networks, but Peterson said there remains a barrier to accessing important information such as what kinds of masks are required in public spaces. Oftentimes, he said, local news go without interpreters, and Deaf/HoH people must rely on their secondary language and inaccurate captioning to understand content.

“When there’s an interpreter there for media coverage, then we can just understand exactly what’s happening and understand it clearly,” he said.

McNair has worked at Sign1News, a news company powered by CNN to serve the deaf/HoH community, for nearly two years. She produces the news show, writes scripts, voices captioning and creates closed-captioning text in English.

She said closed captioning often isn’t enough for deaf people to understand the news. The average reading grade level for deaf people is 5.9, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

“People don’t understand that [English and ASL are] two different languages, and, on top of that, if you only have two Deaf schools in Georgia alone, [Deaf] people don’t get the same access to education,” McNair said.

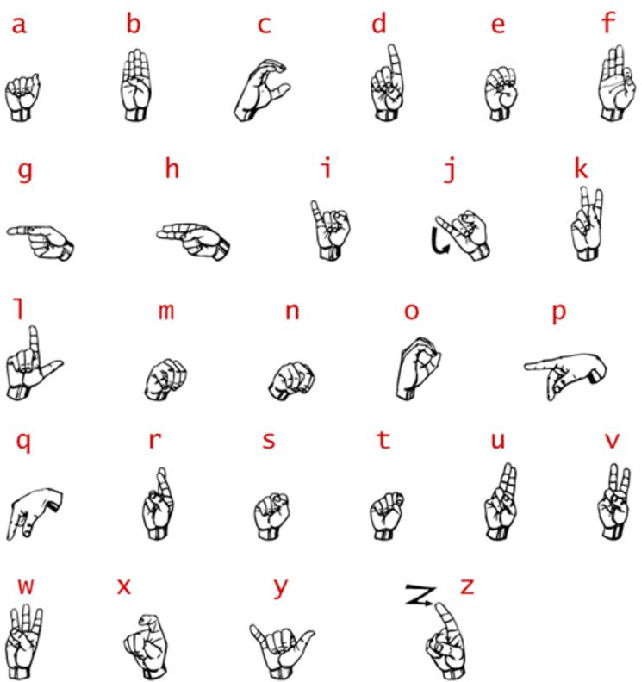

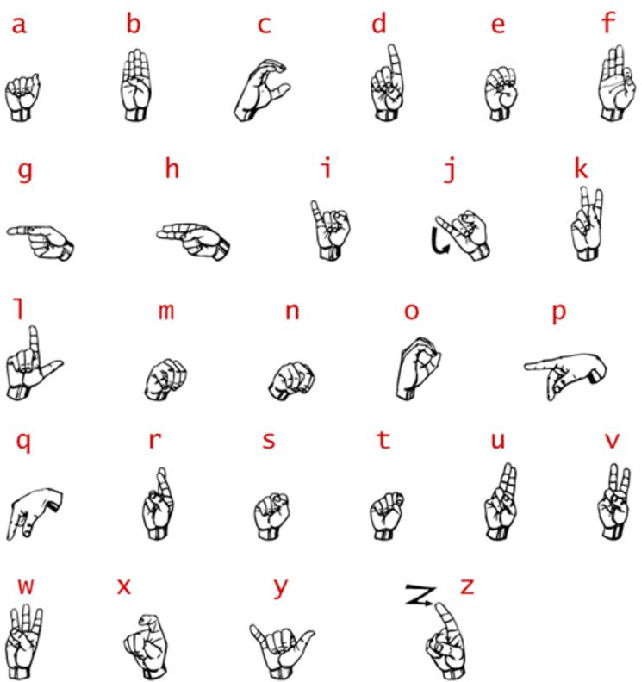

Unlike English, ASL is a visual language that uses hand movements, body language and facial expressions to communicate thoughts. It’s geographically limited to the U.S. and some parts of Canada, but each country has their own sign language. Moreover, ASL is not signed English, but an independent language that has its own grammar and syntax rules.

Accessibility in the news

McNair said having an interpreter available to disseminate news is crucial and empowering to the Deaf/HoH community. Within her work, she noticed an interpreter was cut out of frame during an online emergency weather update and that some briefings would not have an interpreter.

“I don’t think it’s being done on purpose or anything,” she said. “I just think people are unaware.”

Still, McNair understands the importance of quality accommodation in the news.

“Why do Deaf people have to settle for ‘Why don’t you just read [captions] on the screen?’ when they can get [news] in their own language?” she said. “We live in a melting pot, and people should have the right to watch the news the way they deserve to watch it and not be forced to assimilate in a world where they have to settle for ‘Why don’t you watch it our way?’ when [English is] not even their first language for a lot of people.”

Since COVID-19, McNair said she’s felt the effect of her work within the Deaf/HoH community. Comments on Sign1News’s social pages show appreciation for news coverage and accessibility people haven’t had before.

She also said accessible news has been a literal lifesaver.

“We’ve had some Deaf people who didn’t even know what the coronavirus was before our station,” McNair said.

As a result, Sign1News aired special health segments featuring doctors who knew ASL so deaf/HoH people could ask questions about COVID-19. The segments were a big success because people received accessible answers about the pandemic instead of relying on traditional news outlets.

Peterson said Georgia is one of the better states in accommodating Deaf/HoH people. Gov. Brian Kemp has an interpreter for his press conferences, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also hired a deaf interpreter to translate English to ASL to send out informational videos.

“A lot of times we could see what the requirements were, what the diseases were, what were symptoms, things like that,” Peterson said. “That was very helpful when that was sent, so it seems like we have been going in the right direction.”

Modified approaches

The Georgia Center for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing also changed its approaches to serving its community amid the pandemic.

Before, the nonprofit held in-person educational classes, summer camp for children, and community events. When the coronavirus hit Georgia, it had to modify its outreach to the community. Events planned in advance such as health fairs and conferences were held on Zoom in light of shelter-in-place orders in the spring.

Peterson said the unknowns related to the virus and lack of accessible news heavily contributes to fear and isolation within the Deaf/HoH community. Deaf schoolchildren were now having to learn from home in March with hearing parents who don’t sign, and deaf people had to stay home during shelter-in-place orders with limited social contact.

To combat this isolation, Peterson said the community and the nonprofit have heavily relied on social media and video calling to connect with others.

Camp Juliena — the nonprofit’s residential youth camp for Deaf/HoH children — went virtual this summer so children could still socialize. The nonprofit also offers wireless equipment such as the Quattro Pro Bluetooth sound amplifiers for people who are hard of hearing. They've also helped people who have reached out for food stamps assistance and guidance on applying for jobs amid the coronavirus-related unemployment spike.

However, masks in public spaces were often required for face-to-face interactions, hampering communication for Deaf/HoH people. When trying to communicate in public, everyday exchanges such as buying groceries or ordering takeout can be uncomfortable because people often have to take off their masks for lipreading or be close to one another to read texts.

“When the mask — especially the cloth [mask] — covers your nose and your mouth, that actually means that a Deaf person can't see the facial expressions and also can't see the mouth movement, which is huge,” Peterson said. “Those facial expressions and the mouth movement are actually part of American Sign Language grammar.”

Peterson said the nonprofit tried to obtain clear masks that can improve communication during the pandemic, but several vendors are sold out until January, and they’ve had to rely on very few homemade masks.

Silver linings

Despite the challenges, Peterson said the pandemic has provided a big lesson in the importance of family and connection with friends. One of the most special moments during the pandemic, he said, was seeing his two granddaughters for two weeks after months of quarantining.

“I understand the value of my family and my friends more because being able to get together and support each other and chat and have dinners, with coronavirus and having that limited, I didn’t realize what a huge impact it was not being able to socialize,” he said. “And sheltering in place, I realized how much I took for granted.”

Both Peterson and McNair said there’s still ample opportunity to bridge the language gap between hearing and Deaf/HoH people and foster community during the pandemic.

Peterson encourages young people to learn ASL because proximity to sound isn’t a requirement.

“You can talk while you're driving, while you're pulled up next to somebody and still have a full conversation,” he said. “And sign language has no barriers. I think that's an amazing part, and that will really be a bridge and make sure that the communication is easier for people.”

McNair said hearing people don’t need to be experts in Deaf/HoH culture, but a little research could go a long way. She suggests people say “hard of hearing” instead of “hearing impaired,” capitalize D in Deaf to represent the culture and values of the Deaf community, and share Deaf stories.

“When you know better, you do better,” she said. “So when you learn something, just pass it along to the next person.”