Section Branding

Header Content

From Slavery To Civil Rights: The Legacy Of Negro Spirituals In Georgia

Primary Content

On a recent Sunday evening, the sound of Negro spirituals echoed through the halls of the music building at Kennesaw State University.

The six members of the Georgia Spiritual Ensemble gather here regularly to partake in a tradition that dates back centuries.

“Done made my vow to the Lord. And I never will turn back, I will go, I shall go, to see what the end will be,” they sing.

It was 400 years ago, 1619, when the first Africans were brought to America as slaves. It was another 132 years, in 1751, before the practice of slavery was legalized in Georgia.

But, by 1790, slaves made up nearly 33% of the state’s population.

As the economy’s dependence on slavery grew, slaves were often forced to work from sunup to sundown. Sometimes, they turned to music, known as Negro spirituals, to cope.

The tradition of singing those songs carries on today, centuries later. Like with the group at KSU, which Oral Moses founded 14 years ago.

“This music came out of [slaves] as a way to assuage their feelings, to deal with their everyday situations and these songs really sort of sprang into existence,” Moses, a former KSU professor, said.

They were created on the spot and passed on verbally. As Moses notes, “Nobody had time to sit down and write a song.”

Spirituals and civil rights

The music they sang was sometimes referred to as sorrow songs. But Moses said sorrow doesn’t accurately reflect the true meaning of the music.

“If you really listen to the words, they are really fighting back with words,” he said. “And they couldn’t speak. When they were punished for speaking, they put it in a song.”

Songs such as “Oh Freedom,” which exemplifies the spirit of African American resilience.

“And before I be a slave, I’ll be buried in my grave,” as the lyrics state.

That song, along with so many others, presents a widespread theme of Negro spirituals — freedom.

Spirituals, such as “Steal Away,” guided slaves as they turned to the North Star for direction along the Underground Railroad through Savannah’s First African Baptist Church.

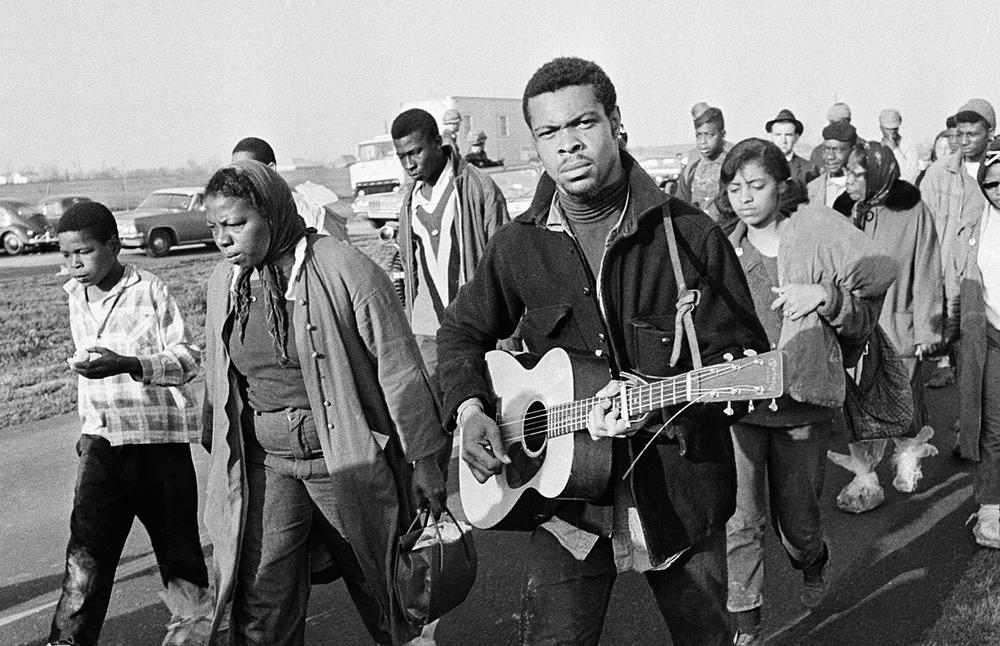

Other songs served as inspiration for African Americans on days like Bloody Sunday as they tried to cross the Edmund Pettis Bridge in Selma, Alabama.

And that’s what David Morrow, a professor at Morehouse College in Atlanta — the city known as the cradle of civil rights — teaches.

He said well after slavery was outlawed, black people continued to use spirituals just like their ancestors.

“What they did in the civil rights movement, very often, was to adapt the text to the current circumstance but use it in the same way,” he said. “Using it to bring people together. Using it to cope with the situation.”

Morrow began to pound the table with his fist as the words built up inside of him before spilling out: “I’m going to keep on walking, keep on talking, marching up to freedom land."

That song, which became popular during the movement, is directly linked to the Negro spiritual, “Don’t Let Nobody Turn You Around.”

“You change the words a little bit and it’s almost the same melody,” he said. “They were using it for marches, so we add that part to it and you have a direct descendant.”

The lasting legacy

The strength of these songs has withstood the slave trade, the Civil War, the Jim Crow era and even now these songs can find their way into popular music.

The Negro spiritual “I Want Jesus to Walk with Me” found its way into the 2004 Kanye West song “Jesus Walks.”

At Baptist churches, you’ll still hear the songs, like “Poor Man Lazarus.”

“Dip your finger in the water, come and cool my tongue ‘cause I’m tormented in the flame,” members of the Georgia Spiritual Ensemble sing.

Ebony Collier lends her voice to these songs as a member of the ensemble. It’s the value of spirituals that drives her to continue to perform.

For her, it’s about finding her identity.

“Slavery wasn’t anything to be ashamed of,” she said. “There was something that came out of that and a lot of people just want to put it behind them.”

She said even more than 150 years after slavery was abolished in America and just six decades after schools in Georgia were desegregated, there’s still a message people can take away from the songs that Africans so earnestly depended on.

“Although we’re not dealing with per se slavery, dealing with the trials that we have today, these songs will still give us a way to hear that there is victory,” she said. “That there is something we can look forward to at the end.”

It’s the legacy of Negro spirituals that fuels Collier to sing, that led Oral Moses to start an ensemble, and it’s why David Morrow continues to teach the songs to students at a college that once educated Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Maynard Jackson.

Because if the descendants of those who sang them don’t pass them on, who will?

Get in touch with us.

Twitter: @OSTTalk

Facebook: OnSecondThought

Email: OnSecondThought@gpb.org

Phone: 404-500-9457