Caption

Jewles Gozdick and Mark Dodd with the Georgia Dept. of Natural Resources take measurements of a nesting loggerhead sea turtle on Sapelo Island, GA, on June 25, 2025.

Credit: Justin Taylor / The Current GA / CatchLight Local

Lily Belle Poling, The Current

Like many Coastal Georgians, baby sea turtles may begin to start crawling towards the new Buc-ee’s mega gas station in Brunswick.

In the turtles’ cases, however, a journey towards Buc-ee’s, rather than the ocean, would likely kill them.

The reason for their journey towards the supersized service station? The lights illuminating the I-95 exit to Buc-ee’s.

|

The Brunswick Buc-ee’s, the third iteration of the Texas-based franchise in Georgia, occupies 74,000 square feet and provides 120 gas pumps, as well as its trademark bites, such as its “Beaver Nuggets,” beef jerky and barbecue. This year, the Georgia General Assembly declared March 20 to be “Buc-ee’s Day,” in celebration of “the cleanest bathrooms around” and “a great community partner.” |

The tall lights now brightening the once-dark interchange are visible from nearby beaches. Experts say that light can distract sea turtle hatchlings from moonlight and starlight — beacons which they rely on to make it to the surf.

When sea turtles hatch from their nests in the sand, they naturally scamper towards the brightest point in their surroundings, which, on a completely natural beach, would be the open sky reflected by the ocean. Artificial light, however, often ranks brighter than the reflection of the sky, causing hatchlings to crawl towards it instead of towards the sea.

Jewles Gozdick and Mark Dodd with the Georgia Dept. of Natural Resources take measurements of a nesting loggerhead sea turtle on Sapelo Island, GA, on June 25, 2025.

“Rather than crawling towards the ocean, the turtle hatchlings are crawling back behind the dunes, and in some places, they never find their way to the water, so they don’t survive,” Scott Coleman, the ecological manager of Little St. Simons Island, said. “In other cases, they may be more easily picked off from predators like raccoons or like ghost crabs, or the next morning it might be gulls and other birds.”

The hatchlings can also get too hot and die if they crawl for too long without finding the ocean. Sometimes, Coleman said, he and his team are able to find and reorient hatchlings going the wrong direction, but they aren’t able to find and save every misoriented sea turtle.

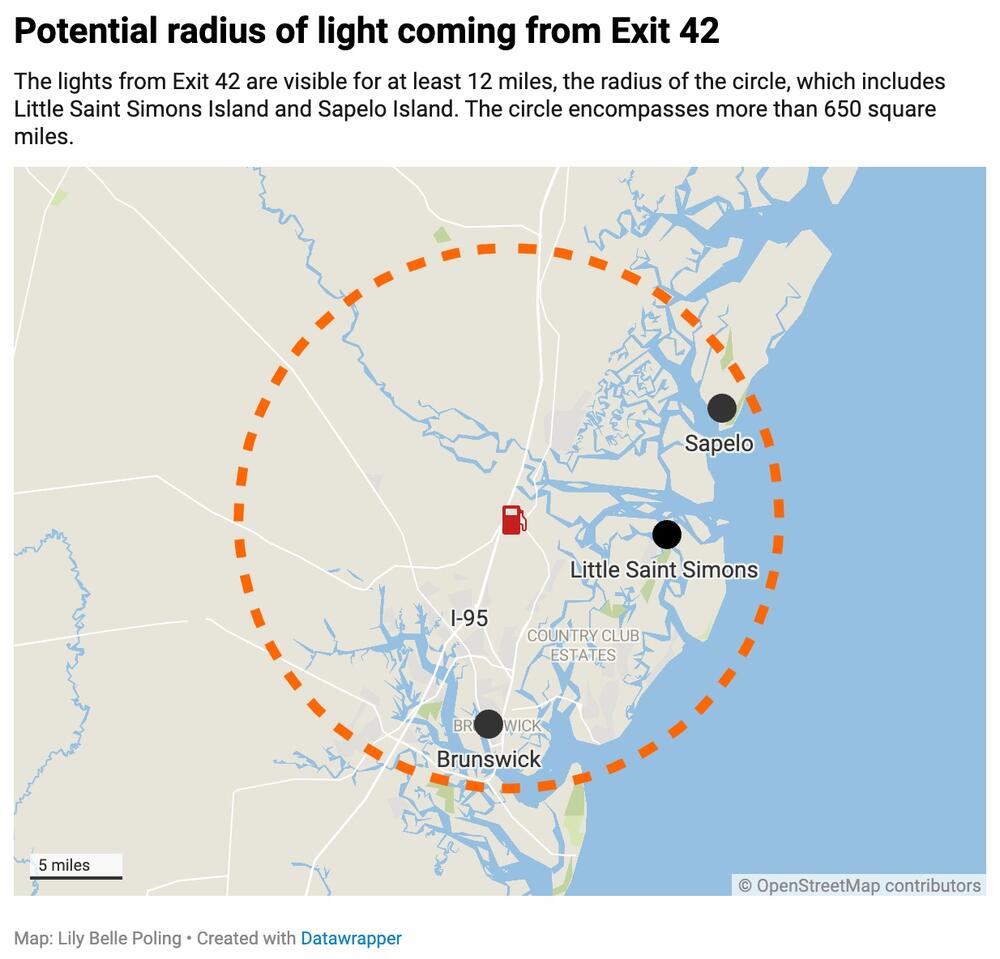

Last summer, 23 high-mast lights were turned on at I-95’s Exit 42, the site of Georgia’s newest Buc-ee’s, which opened July 1. The lights, which shine into the sky and are visible above the treeline, can be seen from the beaches on Little St. Simons Island and Sapelo Island, which are at least 12 miles away.

According to Mark Dodd, a senior wildlife biologist at Georgia’s Department of Natural Resources, rates of turtle misorientations in Coastal Georgia have already been “surprisingly high” in the past three years. Dodd’s division at DNR tracks loggerhead turtle nesting activity in Georgia every year, in compliance with a national recovery plan for the loggerheads — the only sea turtle species that regularly nests in Georgia.

The lights (center horizon) from Exit 42, the location of the new Buc-ee’s, are seen 14 miles away on the beach of Sapelo Island on June 25, 2025.

At Little St. Simons Island, for example, where the glow of the I-95 Exit 42 high-mast lighting is visible from the northern beach, 11 percent of nests had more than 10 misoriented hatchlings in 2024, and in 2023, that figure was 34 percent, DNR’s Wildlife Resources Division’s reports found.

“That’s kind of high for a beach with no artificial light,” Dodd said. “So we attribute that to sky glow from adjacent cities.”

Little St. Simons also has a “pretty low” sand dune field, Dodd said, meaning that there’s little shield from sky glow on the island, leading to increased instances of misorientation for sea turtle hatchlings.

The high-mast lights at Exit 42 could exacerbate that sky glow, which could make finding their way to the ocean even more difficult for the baby sea turtles.

“There’s a lot of new lights at that interchange, and to what extent those particular lights are contributing to sky glow compared with the other new lights that are there, it’s hard to say,” Dodd said. “Those lights certainly can be seen from the beach. They’re unshielded lights that can be seen from the beach, and so they’re capable of misorienting hatchlings.”

But the problem extends beyond hatchling misorientation: Sea turtles are less inclined to nest in heavier lit areas. So while Glynn County beaches do not have particularly high concentrations of loggerhead nests as compared with others in the state, the increased lighting coming from Exit 42 could decrease that density even further.

Volunteer Ashley Raybould, Jessica Thompson, and Mark Dodd with the Georgia Dept. of Natural Resources inspect the site of a sea turtle “false crawl” on Sapelo Island, GA, on June 25, 2025. A “false crawl” is when a sea turtle comes ashore but does not lay its eggs. Light pollution can sometimes be the cause of a turtle not laying its eggs.

“Turtles are the big thing that we’re talking about, but light pollution also plays a huge role in migratory bird migrations as well,” Coleman pointed out. “Birds migrate at night, and we know that there are millions of birds that migrate up and down the Georgia coast. Light pollution is a concern for their migrations, as well, as it can throw them off course.”

A May report commissioned by two environmental justice organizations claims that Buc-ee’s franchises, and other mega gas stations, harm air quality and threaten water and soil, as well. Leaking underground storage tanks, which are a ubiquitous problem with gas stations, are worse at places like Buc-ee’s, the report reads, because of the outsized volume of fuel held at the site.

Multiple communities across the country have organized to convince their local governments to cancel plans for Buc-ee’s, due to concerns about traffic, pollution and the health of small businesses.

Buc-ee’s did not respond to multiple requests for comment by The Current.

The bright lighting coming from Exit 42 has caused many conservationists, including Dodd and environmental advocacy group 100 Miles, to call for stronger zoning ordinances for exterior lighting in Glynn County. The county has been working on updating its zoning ordinances for years and completed an updated draft in August of 2024.

That draft is close to being adopted by Glynn County’s Board of Commissioners, Danny Smith, the county’s public works director, said.

However, while the updated ordinances include stricter exterior lighting policies, the high-mast lights at Exit 42 are not actually subject to Glynn County zoning ordinances.

|

Glynn County sees Buc-ee’s as a big enough win for the local economy that it smoothed a path for the company. The station will employ at least 175 people, its customers will pay sales taxes and eventually Buc-ee’s will pay property taxes. Buc-ee’s spent about $10 million on road construction around the station, and the county spent an additional $3 million, according to Glynn County’s development authority. Instead of regular property taxes, Buc-ee’s will pay an equal amount back to the county every year until Glynn is made whole for the road works. That should take about seven years. After that, the property will go on the regular property tax rolls. Sales taxes will be collected as usual. – Maggie Lee |

|---|

Because the lights belong to the Georgia Department of Transportation, or GDOT, and are located on state rights of way, they do not have to comply with Glynn County’s ordinances on exterior lighting, multiple officials confirmed to The Current.

Dodd has requested both GDOT and Glynn County either turn off or shield the high-mast lights, according to email exchanges obtained by The Current.

However, officials from both agencies told Dodd that the lighting would not be altered by the start of loggerhead hatching season, July 15.

Currently, street lights are being constructed at the Exit 42 roundabouts, which is why the high-mast lights must remain on, Smith and Brian Scarbrough, a GDOT maintenance engineer, wrote to Dodd in emails.

“The current High Mast Lights will need to remain on at night for the safety of the traveling public at these intersections due to the anticipated high volume of traffic with the opening of Buc-ees on July 1st,” Scarbrough wrote to Dodd.

Scarbrough added that the installation of street lights would be complete “sometime around August,” after which the high-mast lights would be “evaluated.”

Aerial view of Buc-ee’s from SouthWings flight, Brunswick, June 24, 2025.

“The concern raised at this specific location has sparked conversations about how to create program-level guidance for lighting along the coast,” Jill Nagel, a communications officer for GDOT, wrote to The Current. Currently, GDOT does “a case-by-case analysis based on environmental sensitivity, driver safety, and practicality” when authorizing the use of high-mast lights, Nagel wrote.

Nagel also mentioned that GDOT has “future plans” to work with DNR “to develop coastal lighting considerations and guidance as it relates to protected species and sensitive habitats,” according to her conversations with Eric Duff and Dan Pass, GDOT’s environmental administrator and design policy engineer, respectively.

“While safety will continue to be a priority for GDOT, environmental sustainability is part of our mission and isn’t at odds with safety goals,” she wrote.

Once the construction of the streetlights is complete, GDOT will consider “replacement” of the high-mast lights, which “Glynn County is amenable to,” Nagel wrote. However, Smith insisted that “Glynn County does not have the authority to turn off the high mast lighting” in his emails with Dodd.

For now, however, sea turtle hatching season is quickly approaching. Wildlife officials generally estimate July 15 as the commencement of that season, but the high-mast lights will remain on until at least the beginning of August, Scarbrough said.

“If you have a light that’s not shielded, that you can see from the beach, generally, that’s enough light to result in the disorientation of hatchlings,” Dodd said.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.