Caption

The program for Joy Harjo's reading with the logos of two sponsoring groups, the Georgia Council for the Arts and Georgia Humanities.

Credit: Grant Blankenship/GPB News

LISTEN: The National Endowment for the Humanities supports art and culture in all 50 states, including Georgia. What do the ongoing federal cuts to the NEH mean for the state? GPB's Grant Blankenship gives us a look.

The program for Joy Harjo's reading with the logos of two sponsoring groups, the Georgia Council for the Arts and Georgia Humanities.

When Soul Harmon boarded a school bus from Macon's Howard High School for a field trip to Middle Georgia State University on a recent Thursday, she didn't know what the day would bring.

Once she and her classmates arrived, they saw a podium on a small stage in the volleyball gym. There former U.S. poet laureate Joy Harjo faced an audience of students, professors and others, and read her work.

“I want to give you this as it was given to me,” she began a poem. “Gifts of inspiration often come when we don't expect it, when we need it.”

After she finished reading, Harjo, the first Native American poet laureate, took questions from the audience. Soul Harmon had what Harjo called a good one. If you had a biopic, what would it be called?

“It would be, maybe, ‘Dancing with My Mother in the Kitchen,’” Harjo said after some consideration. Then she turned the question to Soul.

“And what about you?”

With that, a question became a conversation.

“I've written this poem called ‘Weeping Willow.’" Soul said. "So it'll probably be like that. Like...it's how it's like beauty, but it went through a journey."

“Oh, cool,” Harjo responded. “My mother wrote a song called ‘Weeping Willow’.”

“That is dope,” Soul said to the supportive laughter of the rest of the room which had been watching the student and the poet connect.

Later, Soul said she felt it.

“I feel like it was vibing, yeah,” she said.

Soul said if you‘d asked her earlier in the morning, she may have said she was done with poetry after "Weeping Willow." It was just too painful, she said. But that conversation with Joy Harjo?

“I guess that might be a segue.”

To picking up the pen again.

She said she wasn't expecting that on a Thursday.

Mary McCartin Wearn said that was the plan all along.

“I worked very hard to get those students into that room, because they don't know they want to be there till they get there,” Wearn said.

Wearn is the new president of Georgia Humanities Council, the nonprofit which, alongside the college and other partners, brought Harjo here.

“We're connectors and conveners,” Wearn said.

That takes money. For Georgia Humanities, that money comes from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Among the ideas in President Trump’s proposed federal budget is completely ending the NEH. That comes on the heels of Elon Musk’s so-called Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, zeroing out the NEH $200 million budget.

That took out Georgia Humanities's annual operating budget of about $1.5 million a year with it, too. That’s like 15 cents per Georgian per year, some of which Georgia Humanities has spent this year but which they won’t be reimbursed for.

That’s to pay for the recent National History Day where young people from across the state to present research projects. After the budget cuts, it’s unclear how students who made it to the national competition can afford to go. And Georgia Humanities is also out of pocket for some of the money it took to bring Joy Harjo to Macon and ultimately to inspire Soul Harmon.

The money also helps resurrect voices from the past.

Photos of Chester Davis and his jacket on display in the new exhibit at Macon's historic Hay House mansion devoted to the Black people who during and after slavery ran the house. You can hear Davis' voice in part of the current house tour.

Today, mounted on the wall of what was once the kitchen in Macon’s palatial, Civil War-era mansion called the Hay House (owned by the Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation) is a photo of a man named Chester Davis.

He’s beaming in the image and dressed in a crisp white coat. He was a driver for the home’s owner until the 1970s, when Davis became the first tour guide at the Hay House.

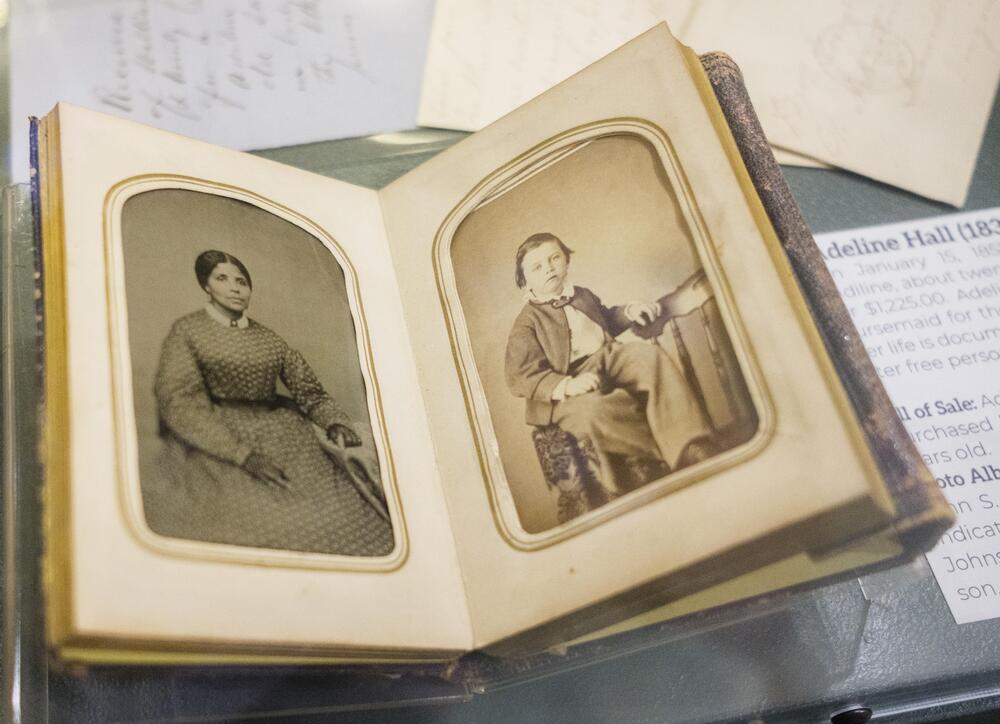

On the opposite wall are two photos of a woman named Adeline Hall, one taken when she was the enslaved nanny of the children in the house and one many years later when she was emancipated but still working for the family.

Hay House director Aubry Newby said it took about a decade to get the proof of the lives of the African Americans like Davis and Hall — who literally made the Hay House run — out of storage and on full display in the new kitchen exhibit.

“It would probably not have happened had the Georgia Humanities grant not been available to us,” Newby said.

The grant was for $2,500. Newby said the dreamed-for exhibit just wasn’t in the budget otherwise.

Lots of small museums have seen help like that across the state for almost 55 years, since Georgia Humanities began as one of the first state humanities councils in the nation.

Thsi photo album with a photo of then enslaved nanny Adeline Hall, left, and one of the children she had been charged with raising, right, had been in storage before a Geogia Humanities grant.

Ann McCleary has seen it in her work with Georgia Humanities bringing Smithsonian exhibits to small towns.

“Communities came together and made up banners that they could stretch across the road that said, ‘The Smithsonian is here! The Smithsonian is coming!’” she remembered.

When the federal cuts came, she was helping coordinate the next Smithsonian exhibit for 2026 called "Voices and Votes: Democracy in America." Like older exhibits, she expects this one to start conversations.

“I think that's what humanities programs are: they're conversations,” McCleary said. “And that is what we need to have. We don't all have to agree, but we do need to talk.”

It’s still not clear how further downstream the Georgia Humanities Council can afford to help make those conversations happen.

A few weeks after DOGE zeroed out the NEH budget, the philanthropic Mellon Foundation announced a multi-million dollar donation.

It’s just a fraction of the total of the federal cuts.