Section Branding

Header Content

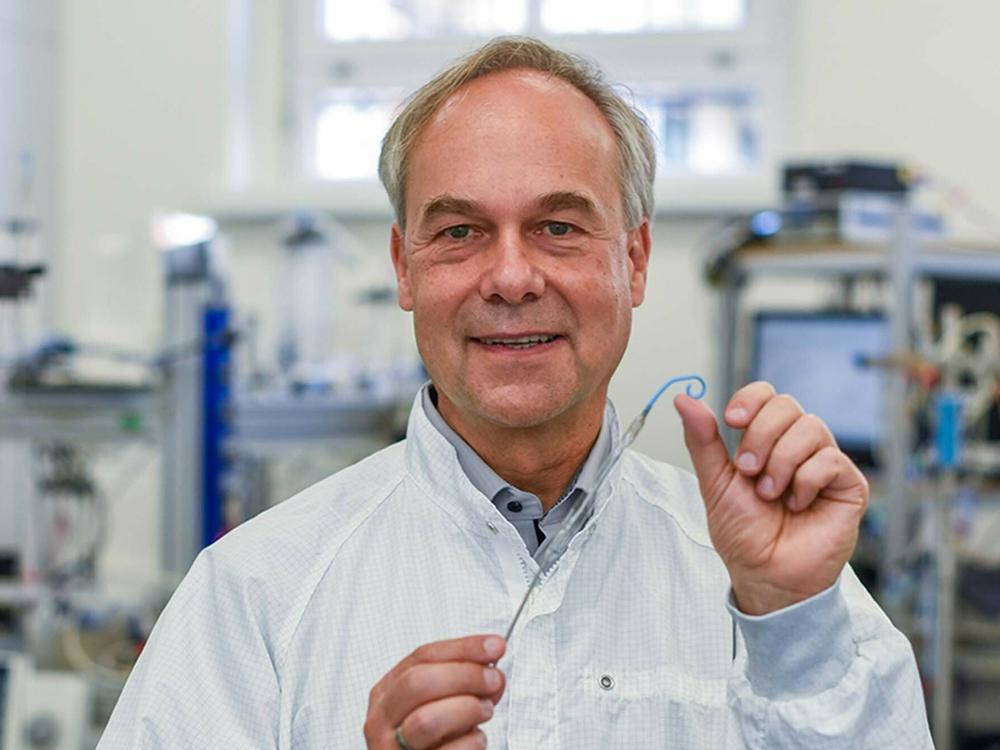

He invented a successful medical device as a student. Here's his advice for new grads

Primary Content

When he was 25 years old, Thorsten Siess, a mechanical engineering student at the University of Aachen in Germany had an idea: What if there was a way to keep the heart pumping blood during surgery or following a heart attack with a device that affixes a tiny motor to the tip of a catheter?

"This would be able to be put into patients without the need for a major operation," says Siess. "Normally, of course, you would have to split the sternum."

Today, Siess's idea is a reality — a medical device called the Impella — and he serves as the chief technology officer of Abiomed, which is part of Johnson & Johnson.

After meeting a professor he described as a "cool dude" in the 1990s, Siess wrote his own grants to get him through his PhD and founded a startup to make the Impella.

It's designed to help some of the highest-risk patients who "already had prior surgery and prior interventions," he says. "They are considered to be so high risk that none of the treating physicians would usually touch them."

Doctors insert the Impella through an artery in the patient's leg and guide it up to the heart's pumping chamber. There it pulls blood in and pushes it out into the rest of the body using a tiny turbine that has to be gentle enough not to burst the red blood cells.

In 1999 Siess remembers being nervous when the first human patient was treated with the Impella, a woman named Claire. He says he recently met her again, and she hasn't had any more heart problems.

But back in the university lab more than two decades ago, Siess says his device didn't look like much. It took him years of work, to get others to share his vision, to start a company and get the device OKed by the Food and Drug Administration.

Now he has advice to aspiring inventors and new grads.

"Don't be disappointed that the first things don't work as intended," he says. "They don't look nice, but you see the potential of what you're doing."

He also stressed the importance of teamwork and doing something that truly interests you.

"The things that really move the world seemed to be impossible 10 years ago," he says. "Pick something that you think is worth your time and effort, something which is not so easily done, and then go with it."

He says new grads should aim high and stick to what they're passionate about. "Because otherwise, if it doesn't interest you, you're not going to put all your energy into it and go maybe for the 'mission impossible.' "

To be sure, there are still risks and benefits when it comes to the Impella.

Earlier this year, Abiomed recalled the device's instructions because it received reports the device could perforate part of the heart. It's called a corrective recall – the Impella can still be used in patients but the company needed to update its instructions, and the FDA is continuing to evaluate new information as it becomes available.

"Our instructions for use have been updated with stronger technical guidance around implantation and repositioning," the company said in an emailed statement.

Still, a recent study published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed people were more likely to survive with the Impella than without it after a serious heart attack with cardiogenic shock.

The study also found that these patients were more likely to have complications. That's likely because these patients are sick and often need things like CPR, which is complicated with a device inside the heart, says Dr. Richard Kovacs, chief medical officer of the American College of Cardiology.

"It's been an improvement in our care, but it's a tool in our toolbox," he says. The Impella fills an "unmet need," he adds, by treating a subgroup of heart attack patients who would otherwise die 50% of the time from a kind of shock that prevents the heart from meeting the demands of the body.

As for Siess, he says he remembers graduation day as a wonderful time. He had already started his company and believed in the Impella, but nothing was certain yet.

"Had I not had the grit, the perseverance and the belief that this was going to make a difference in patient lives, I'm not sure that I would have survived the program."

He never dreamed the device would be used in some 300,000 people.

"The most gratifying thing in my career to be able to do something positive for the people and the families – it's one thing I never thought I would be able to do as a mechanical engineer," he says. "But it all started with a vision."