Section Branding

Header Content

As a writer slowly loses his sight, he embraces other kinds of perception

Primary Content

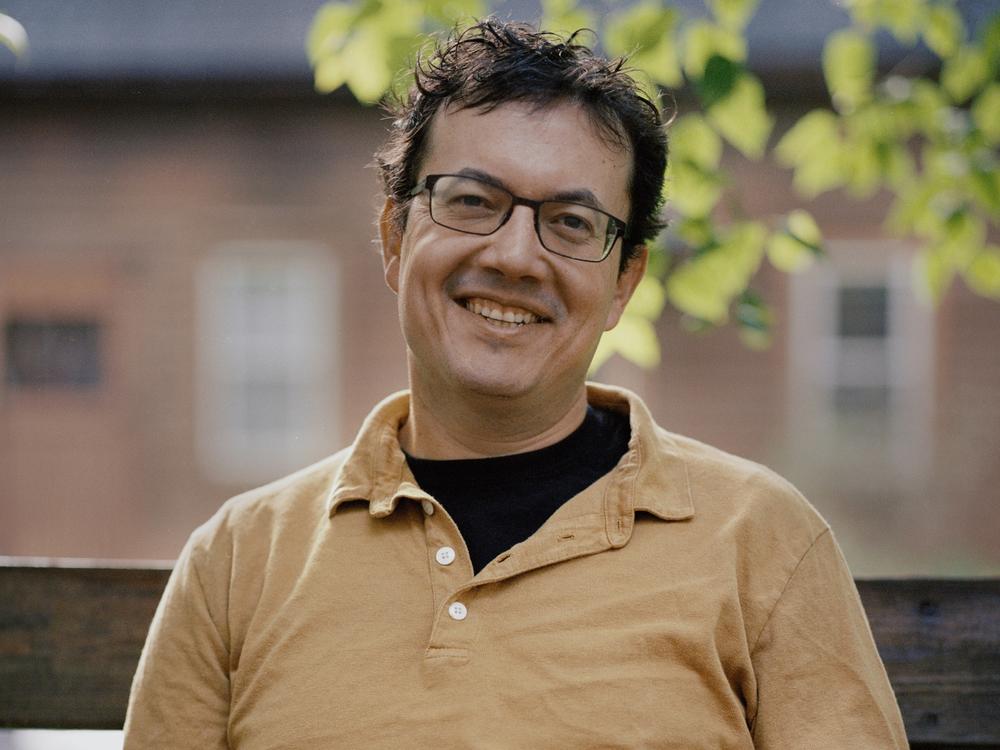

Writer Andrew Leland started losing his sight 20 years ago, when he was in high school, as a result of a progressive eye disease called retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited condition that leads to the deterioration of the retinas.

Leland first experienced it as night blindness, in which he was confused that everyone else seemed to see in the dark so much better than he did. Over the years, his disease progressed gradually. He's now legally blind, although he still has a narrow field of vision, which allows him to see about 6% of what a fully-sighted person sees.

Leland likens his vision to the view you might get by looking through a toilet paper tube or a keyhole.

"It's really a narrow aperture that I'm pointing around," he says. "Imagine having that toilet paper tube strapped to your head and trying to walk down the street; there's this whole field of things that you don't see that you really ought to, like curbs or toddlers or dogs or fire hydrants."

In the new memoir, The Country of the Blind, Leland writes about losing his vision and preparing for blindness — and how his condition impacts his identity, how the world sees him and his marriage.

Contrary to what many people think, he says, his blindness is not a state of "lights out — total darkness." Rather, he describes the progression of his disease as a "drip-by-drip" vision loss, in which even the question of when one becomes blind can be confounding.

"The place I'm at now is I want to be able to enjoy vision, and I want to be able to enjoy everything from my son's face to TV that we're watching," he says.

"But practically speaking, I have to learn the skills and I have to be able to function without [vision], because it comes and goes during the day, depending on light conditions or my eye fatigue. And also, the fact of my condition is [my vision is] going to go away over the next few years."

Interview highlights

On what it means to be legally blind

Blindness being a spectrum, it is a sort of arbitrary metric that really only emerged when government assistance programs had to sort of decide who was eligible. And so there's two main ways that legal blindness is measured: One is in acuity and the other is visual field. So acuity means if you can't read that giant E at the top of the chart with corrective lenses, you're legally blind by that measure. And then the one that affects me is visual field. So if you have I think it's 20 degrees of vision or fewer and I have something like six degrees, then you're legally blind.

On being both inside and outside the blind community

One of my first encounters with a blind community was when I was living in Missouri ... and there was a meet up of the National Federation of the Blind local chapter, and I had no idea what that was, but I was just starting to feel more isolated and more blind, and I wanted to find a community. So [my partner] and I went and we showed up late. So most of the blind people didn't know we were there and the sighted people there didn't alert anyone to our presence. And so we really were just standing at this uncomfortable remove at this park under this gazebo. And I felt very uncomfortable.

And I'm struggling to explain exactly what it was. It's something that I experienced as a non-disabled person my whole life, just this feeling of difference and almost fear. I don't know what I was afraid of. It's not like I'm in any danger, but it was like a fear of difference. And I think that was certainly exacerbated by the sense of like, is this me? Am I now a part of this sort of sad, strange world? I think there's certainly pity there. ... I hated myself as I had these feelings. ... If I really wanted to boil it down, it's just a fear of difference.

On not letting his blindness diminish his work

I did encounter statistics about, for example, violence against people with disabilities, and it is documented that people with disabilities are assaulted and victims of violence, including sexual violence. So I want to be very clear about that dynamic. But I don't think it's helpful to hear a statistic like that and then say, "OK, I am now de facto more vulnerable in the world and I should change in some fundamental way what I'm going to go and do." So I don't feel more vulnerable, necessarily. But I do have to rely on other people to help guide me in certain situations.

On how his blindness affects his marriage

Every marriage has that negotiation of who's doing what, and is there parity? I did the laundry, but you did the dishes. And I think certainly her life has changed just in the sense of she's the driver. And then there's other more subtle things like in our house, if there's lead paint that's chipping, I'm not going to see those paint chips. So I think there's like a sense of visual vigilance that she has that she wouldn't she might not otherwise have. And I think that that can create tension, certainly.

I really have made an effort to not be the kind of blind person who just says, "Well, I don't see very well. And it's going to be so much easier for Lily to find the trash can in this restaurant. I'll just let her clear our table," [and] instead to say, "It's going to be annoying and I might bump into a stranger's table or I might go into the wrong corner at first, but I don't want to be that guy just sitting there and letting her do everything for me." So one of the things that I think about a lot is ways in which I can push back against that inertia.

On something he learned at a blind training center

All of the instructors at the center are blind. And so you're out there in Denver intersection with a blind instructor wearing sleep shades and they say, "OK, cross the street," and they teach you how to listen to traffic and how to feel the curb with your cane to get yourself perfectly oriented and to know exactly when it's safe to cross. And that skill I'll take with me for the rest of my life.

It's almost like balancing a stereo. Like you listen to the traffic crossing in front of you and you want to make sure that you can hear the car beginning to approach in your left ear. And then it sort of exits through your right ear and the tip of your nose has to be sort of finely balanced. And you use that and you kind of balance that with the parallel traffic going, you want to make sure that feels like it's right, on your shoulder and then you feel the curb and then once you hit some of the traffic patterns and you have a sense of when it's time to go, then you go.

On sight not being the most important thing

I'm not going to try to tell you that having vision is not an incredibly useful thing for a human being to have for a myriad of reasons. But when we talk about the experience of being alive and of being conscious, when James Joyce was going blind, to paraphrase him, I'm only losing one world among many, and vision is only a tiny sliver of experience.

I think if you look at the things that blind people are capable of imagining, [like] John Milton writing Paradise Lost as a blind person, there is this incredible richness to consciousness that vision has nothing to do with. And the tactile realm, the audible realm, the mental realm, the emotional realm — it's all so rich that I don't think vision ... [is] the ticket to entry to understanding the world that most people suggest that it has.

Heidi Saman and Seth Kelley produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Carmel Wroth adapted it for the web.

Copyright 2023 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.