Caption

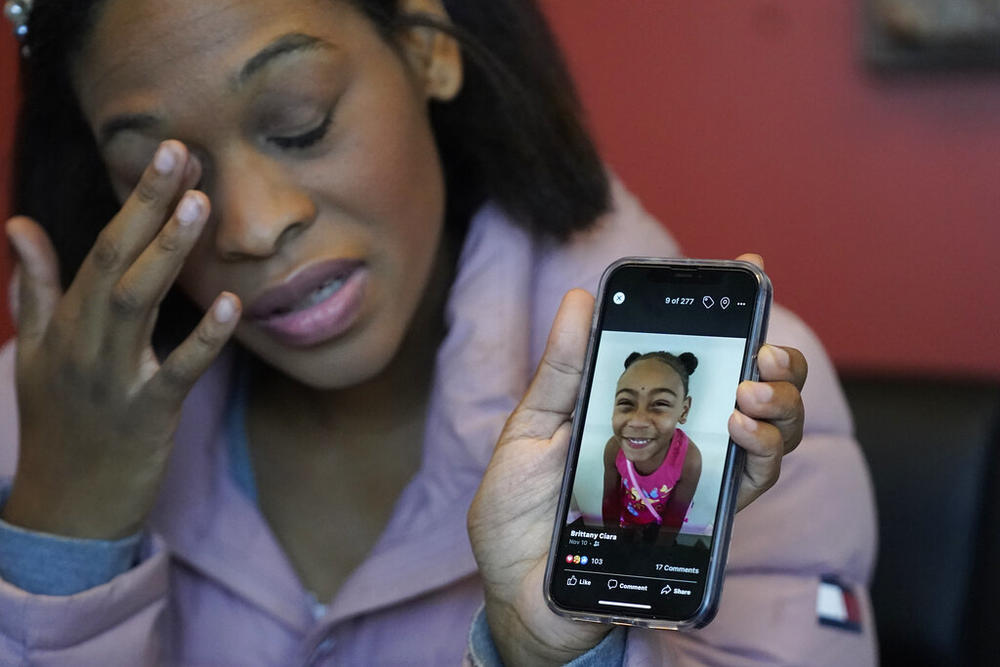

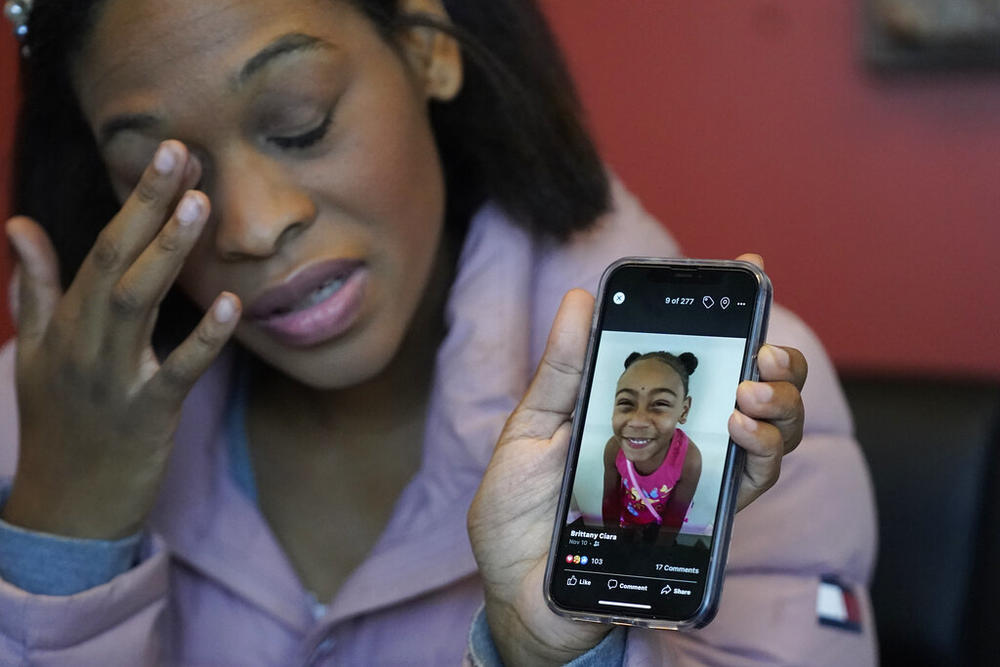

Brittany Tichenor-Cox holds a cellphone with a photo of her daughter, Isabella “Izzy” Tichenor, who died by suicide in 2021.

Credit: (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, File)

LISTEN: A new study of commercial insurance spending nationwide finds the number of children and youth being treated for mental health concerns rose between 2019 and August of 2022. GPB’s Ellen Eldridge reports on what is likely driving the increase.

Brittany Tichenor-Cox holds a cellphone with a photo of her daughter, Isabella “Izzy” Tichenor, who died by suicide in 2021.

Several new studies indicate children’s mental health is worsening nationwide, in no small part due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

School closures, social distancing and the loss of family members over the past three years contributed to an increase in commercial insurance claims for children’s mental health services, especially telehealth, according to a survey published Oct. 3 in JAMA.

While attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, and adjustment disorders accounted for the most visits and mental health insurance spending between January 2019 and August 2022, suicide was the third leading cause of death in 2021 for Georgians between 10 and 34 years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC reported a total of 1,676 deaths by suicide.

That number is likely an undercount due to issues with reporting on death certificates.

Alarmingly, the firearms suicide rate among Black teenagers nationwide surpassed the rate for white teenagers for the first time on record in 2022, according to a July data analysis by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions.

Another of the more alarming trends John Hopkins identified in the CDC data was how gun deaths continued to rise for children and teens ages 1 to 19 in 2022. The firearm death rate for that age group was the second highest rate in 25 years, behind only 2021. From 2013 to 2022, the gun death rate among children and teens has increased 87%, fueled by both homicides and suicides.

Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions also offered specific policy ideas to help reduce firearm violence, including investment in community violence intervention programs.

The behavioral health crisis system of Georgia comprises community, inpatient and outpatient services for individuals at or below 200% of the federal poverty level. That’s without private insurance, Medicaid or Medicare.

But even with the means to pay for treatment, specialists for child and adolescent mental health are hard to find in Georgia. For example, there are 240 child and adolescent psychiatrists listed on the Georgia Council for Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists roster, but doctors are concentrated in the metro Atlanta area, making medication services difficult to access in rural parts of the state.

Voices for Georgia’s Children analyzed data and found that 41% of children ages 3 to 17 struggle with access to needed mental health treatment and counseling, but even those who ask for help can be turned away.

If a parent or guardian refuses treatment for their child, there is nothing a therapist can do, said Kathryn Allen with Thriveworks in Atlanta.

She has experience working in foster care and school systems.

“And this is the unfortunate part: Unless something serious happens to where a mandated reporter has to step in and report this behavior, there's not really much a clinician can do,” Allen said. “We cannot go over a parent's head and say, ‘Your child is required therapy’ unless they are harming themselves.”

One of the things the commissioner of the state Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities is doing is asking for more crisis facilities in more communities. A study shows some existing facilities don’t have the staff to fill available client beds.

"During COVID, the hospital section of our department lost over 1,200 employees," Commissioner Kevin Tanner said. "It really decimated this department and our ability to provide services at our state hospital."

Tanner added that without bringing crisis beds back online, the state won't be able to fix these problems.

Additionally, eight new behavioral health and crisis centers are needed in the next 10 years, a recent bed capacity study shows.

"I'm excited about the potential there," Tanner said, noting that the amended FY 2024 budget contains $15.5 million to fully fund the new Child and Adolescent Crisis Stabilization Unit down at Savannah.