Section Branding

Header Content

What to expect when Cephalopod Week comes to Atlanta

Primary Content

Cephalopod Week is the annual celebration of octopi and the like.

As part of this year's celebration, Science Friday partners with GPB to salute the ocean's super-smart invertebrates on June 28 at 6 p.m. at the GPB Studios in Atlanta with Science Friday host Ira Flatow.

You can purchase tickets here.

GPB's Grant Blankenship spoke with Flatow about octopuses and squids to find out what makes cephalopods so great.

Grant Blankenship: I think of Cephalopod Week as a tradition at this point, and I'm always excited when I hear it pop up on the radio every year. How — how did you even start this and why?

Ira Flatow: Yeah, it is a tradition. I think we're like in our 10th year of this. It started in a very interesting way. About 10 years ago, Flora Lichtman, our video producer at the time, created a video called 'Where's the Octopus?' where marine biologist Roger Hanlon, he's scuba diving and stumbles literally on a camouflaged octopus. And it just scares him, grabs onto his mouthpiece. And it was amazing video. We put it up on YouTube, it's got about 600,000 views now. And when we saw this video, we said, 'Hey, you know, there's this thing called "Shark Week" on that other channel. Why don't we celebrate a much brainier, more interesting kind of animal — the cephalopods, squid, octopus, cuttlefish or nautilus — which are magicians of disguise and a lot smarter than sharks? So we'll have our own "Cephalopod Week."' And that's how it happened.

Grant Blankenship: They are super smart, and so various in their forms. Are those the things that make them such a great entree for people into literally the rest of the world of science? Is that why this sticks?

Ira Flatow: Well, you know, what's interesting about them, why it sticks, I think, is because they're so surprising. There was a famous story where a marine biologist had octopuses in his tanks, and every night he would shut the lights off and in the morning he'd come back and there was a fish missing from one of the tanks on the other side of the room, and he couldn't figure out what was going on. So one night he closed the lights, shut the door and stayed in the room, and he watched an octopus sneak up out of the tank, crawl on the floor all the way over to the other side of the room, go up into the tank, go fishing, steal a fish, and go back into his home. So how could you not love that?

Grant Blankenship: How could you not love that? Exactly. Did you see that story recently about the scientist who thought he was watching an octopus in his lab have a nightmare?

Ira Flatow: I did. I saw that story, and I thought it was crazy, right? I mean, you watch it sort of sleeping, and then it starts going into wild contortions. And in the middle, just about halfway through, it inks itself — lets out this big ink, which we all know is its defense. So maybe it had a nightmare about it being attacked. Of course, we don't know if octopuses even dream, much less have nightmares. So it was really, really interesting. And it's, it's more — it adds to the lore about the cephalopod.

Grant Blankenship: So for the cephalopod-curious who are maybe landlocked and can't scuba dive, what's the best way for us to engage with them? How do — how do we get close contact with these animals?

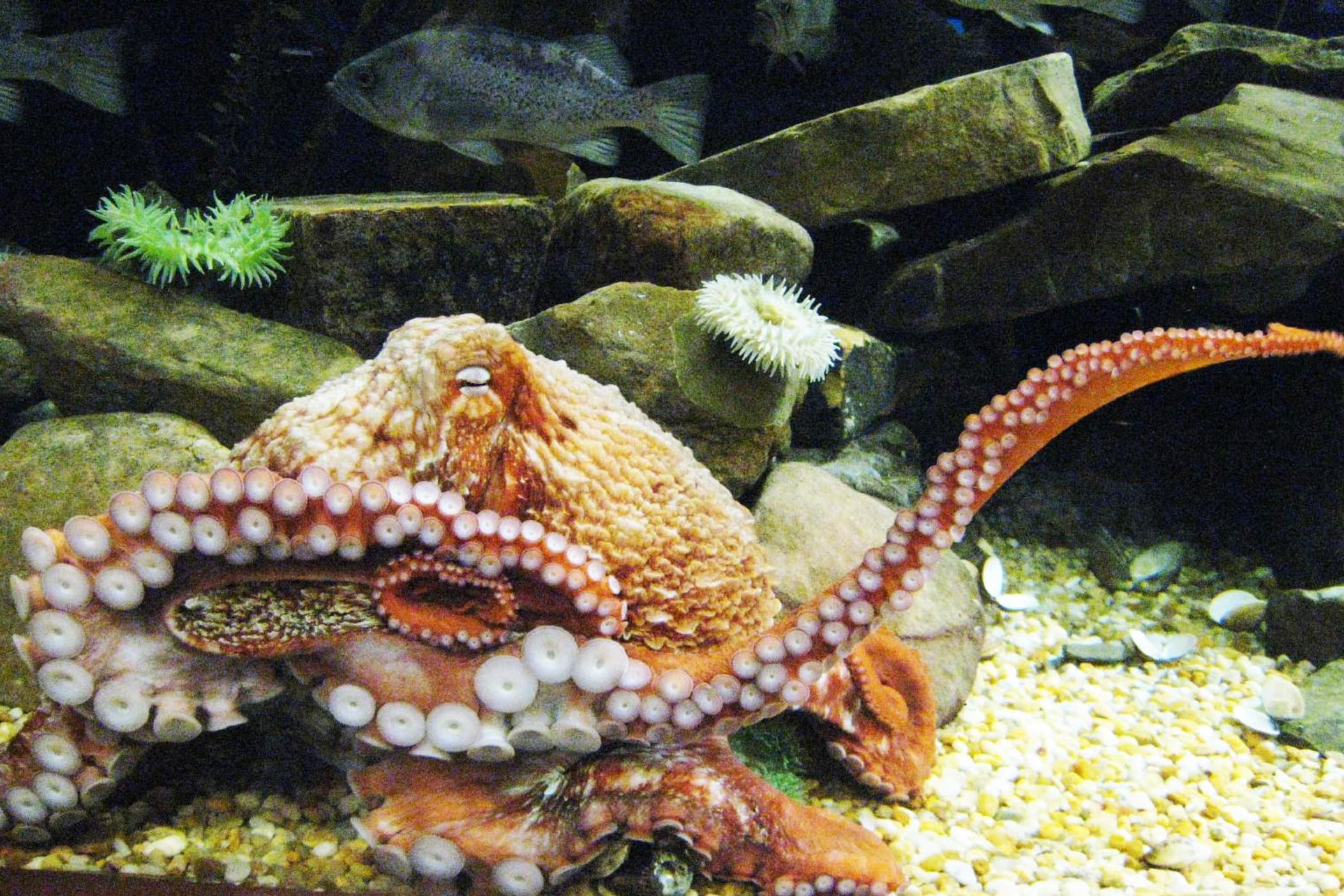

Ira Flatow: Well, you know, there are aquariums that have cephalopods in them and they allow you to, you know, get up close and personal with them. You don't want to — you don't want to hurt them, I mean, and the aquariums won't allow you to do this. But, you know, if you can't get to the cephalopods, go to the petting zoos in the aquariums and — and react with those animals that they can allow you to touch.

You could become a scuba diver and you could go underwater and look for an octopus. The dive masters know where they live. I found one when I was diving. The dive master took me to the pilings in a pier. Because octopuses — octopi, whichever you prefer — are nocturnal, they like to come out at night. And he beckoned me over to this octopus, and I swam over. And he had one in his hand. He's gesturing to me, 'Hey, come, come, feel this.' And I'm sort of afraid because I've never touched an octopus. But he took the octopus and he sort of tilted his hand and it went into my hand. And you know what? I could hardly feel it because it's probably 98% water. And I'm in the water, so I'm just gently touching it. And it was one of the great moments of my diving experience. And I think that's the best way: It's to go out and go learn how to scuba dive and go see them in their natural habitat because they will do things in their natural habitat that you won't see them do in captivity because they're at home out there and there they're the boss.

Grant Blankenship: What research are you watching most curiously? What's — what's the stuff that you're looking forward to scientists telling you that you want to know about these animals?

Ira Flatow: Well, you know, climate change is here. Global warming is happening. That means the oceans are getting warmer. And when the oceans get warmer, a lot of different stuff happens. When the oceans get full of carbon dioxide — they really suck up a lot of CO2. And when you suck up CO2, it turns into an acid in the water. So it's like if you have soda water: If you bubble CO2 through the soda water, you're actually creating an acid. The water gets more acidic. And that's bad for all sea creatures because they're not used to living in acidic water and they're not used to living in warming water. And it doesn't take much warming in an ocean to affect the marine life there. We're talking, you know, a fraction of a degree. So, so many researchers are looking into how climate change is affecting all the animals in the water. And the octopi and the cephalopods are certainly part of that family. We won't know what's going to happen.

Grant Blankenship: For folks who come see Cephalopod Week in Atlanta at our studio, what can they expect? How is how is this experience going to be different?

Ira Flatow: It's going to be. It's going to be a lot of fun. We always have fun at these. OK, so the audience is going to hear from two really amazing local experts. Emily Green is an aquarist from the nearby Georgia Aquarium with almost 10 years of experience caring for cephalopods and sea jellies, turtles, under — other underwater creatures. And then we have Nicole Johnston, a biology lecturer at Spelman College who teaches about coral reefs and ocean acidification due to climate change. Plus the audience. I love this: The audience can ask them questions. And you know what happens? I have to I have to warn the audience in advance because this happ- — we do this a lot — when we get to a Q&A period and we ask people for questions? People are shy about going up to the microphone and you know what happens? The kids get there first.

Grant Blankenship: As they should.

Ira Flatow: Yeah. A 9-year-old is going to muscle you out. And if you want to get a question in, make sure you get there early because —they ask the best questions. So that's actually the best part, is the Q&A part. I love that.