Caption

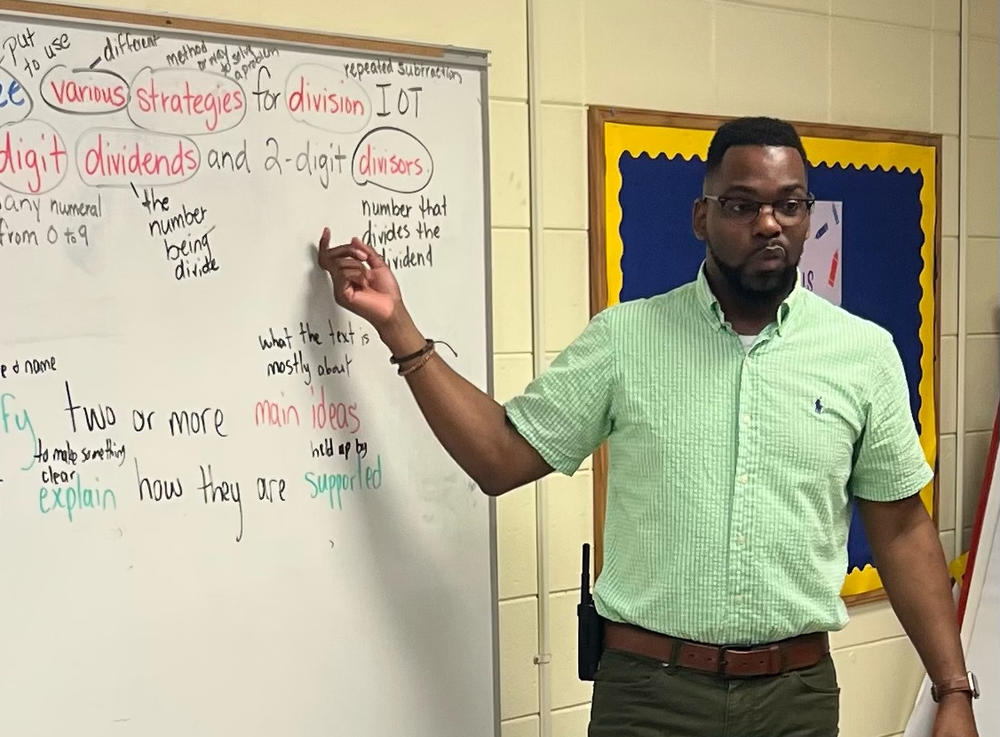

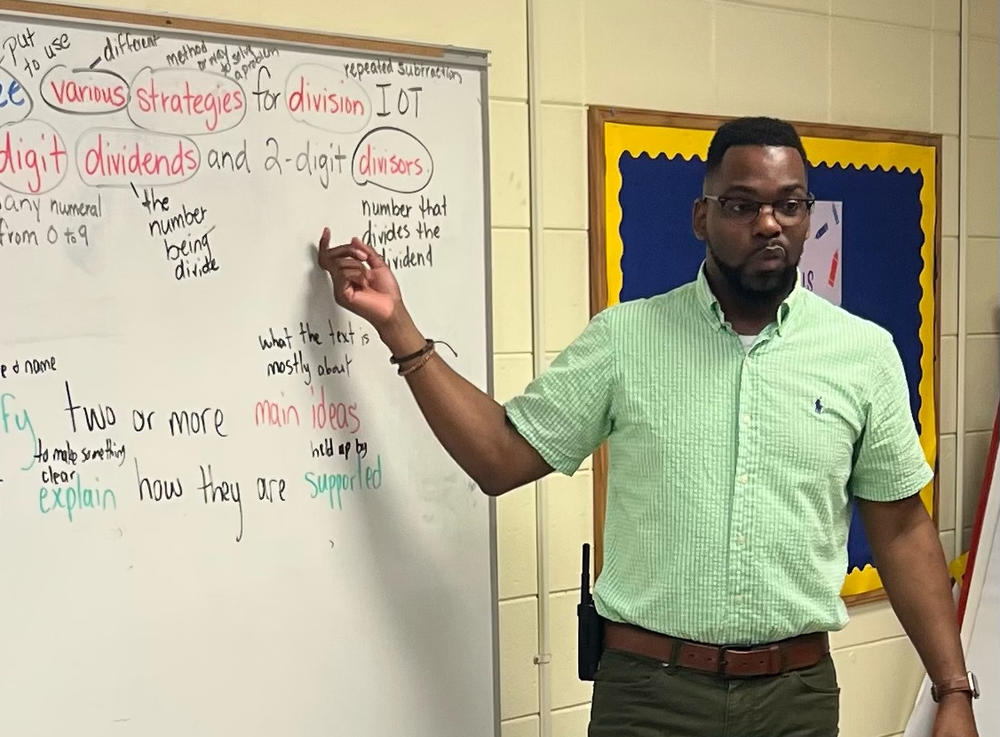

Daerzio Harris is a fifth grade math and science teacher at Jeffersonville Elementary School in central Georgia and a contributor to the Department of Education's report on teacher burnout.

Credit: Courtesy of Daerzio Harris

GPB's Peter Biello speaks with three Georgia teachers about their experience with burnout.

Daerzio Harris is a fifth grade math and science teacher at Jeffersonville Elementary School in central Georgia and a contributor to the Department of Education's report on teacher burnout.

A recent survey from the National Education Association finds more than 50% of teachers are thinking of leaving the profession. One of the causes? Teacher burnout.

It was one reason Lee Allen left his high school teaching position for a similar job in a smaller district. He was named Gwinnett County 2022 Teacher of the Year. He said he’s worried about feelings of burnout among teachers snowballing.

“Almost all teachers are there because we care about and love helping others," Allen said. "And I’m worried about in five years when teachers who are just hanging on until retirement have retired and gone — and a lot of mid-level teachers are looking for careers elsewhere. That really concerns me.”

A report issued last month from the Georgia Department of Education looked at the causes of burnout among Georgia’s teachers. Those causes include too much time spent in meetings, unrealistic expectations and an ever-increasing workload.

Michelle Mickens is an English teacher as Washington-Wilkes Comprehensive High School in northeastern Georgia. She's one of the contributors to the DOE burnout report and says the workload has been increasing for years.

"This is a problem that's been building," Mickens said. "It's not just a result of the pandemic."

Mickens said in her district, the school day now starts a half-hour earlier than it used to, which has taken away some teacher prep time.

Daerzio Harris, a fifth grade math and science teacher at Jeffersonville Elementary School in central Georgia and contributor to the report, says keeping up with the rising workload has been tiring.

"When I come home and I'm too tired to help my own child do her own homework or spend time with her, that was my breaking point," Harris said.

Nikki Hampton, a STEAM teacher at W.L. Swain Elementary School in northwestern Georgia’s Gordon County School district, contributed to the report. She said that going forward, schools need to assess whether students can realistically stick to pre-pandemic standards.

"We constantly preach about meeting students where they're at," she said. "But on paper, they're supposed to be at point X on the pacing guide. They're not going to be there. So who's accountable for making up that gap?"

Mickens said one possible solution is a four-day school week for children, with the fifth day set aside for teacher planning. She said political leaders at all levels need to line up behind teachers and look carefully at the demands placed on them.

Harris said no one solution works for all Georgia districts. He said a dialogue within each school district about appropriate adjustments may be the best path forward.

"Hopefully this [report] will start some conversations," Harris said. "What can we do next? What do we need to do next to move the schools in the right direction?"