Caption

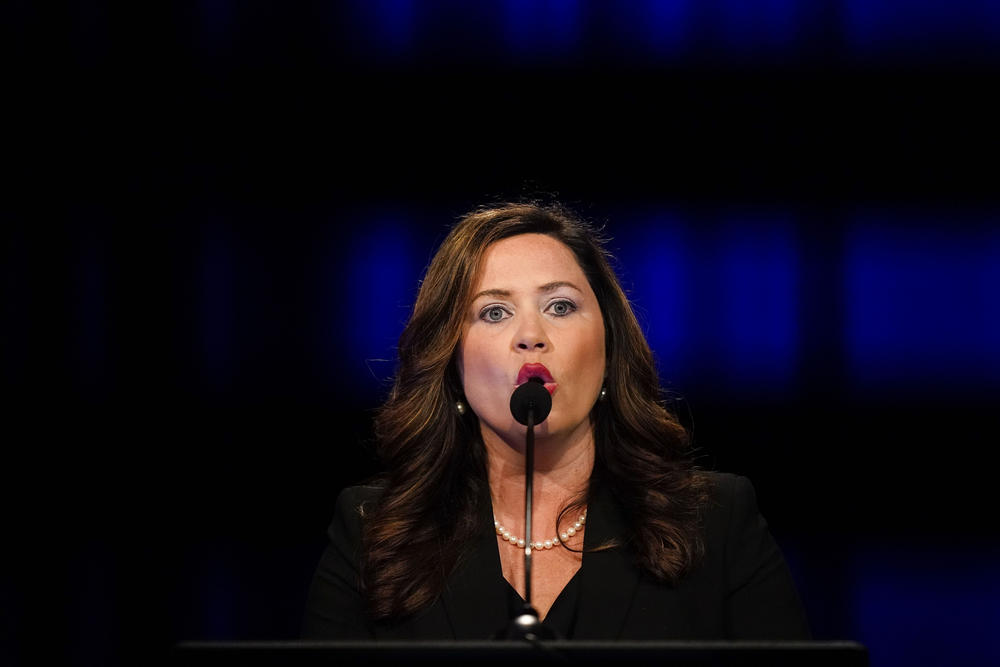

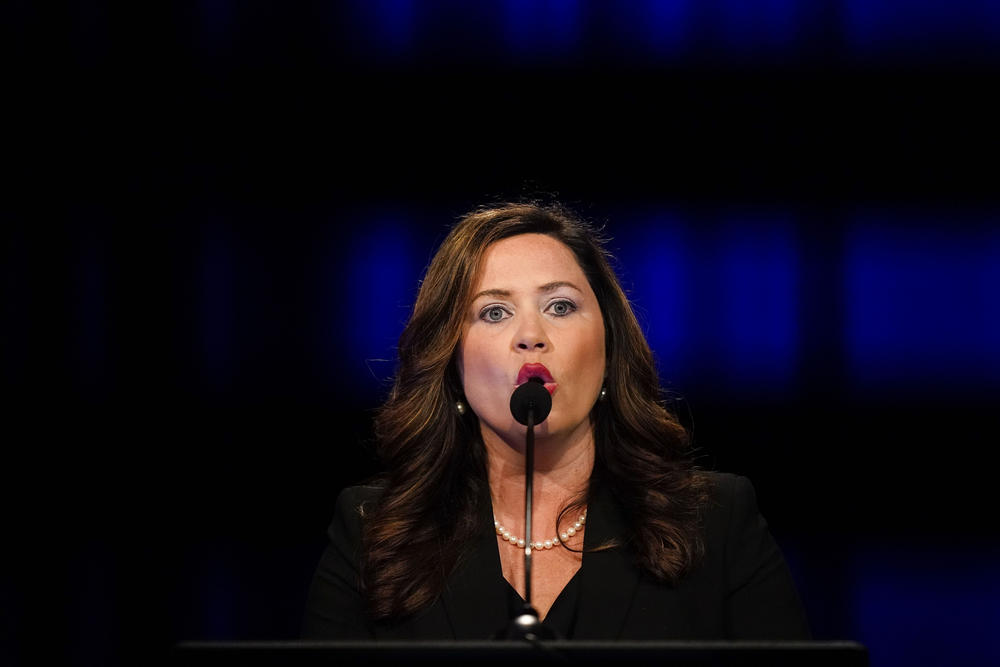

Kandiss Taylor, a Georgia Republican gubernatorial candidate, participates in a Republican primary debate on Sunday, May 1, 2022, in Atlanta.

Credit: AP Photo/Brynn Anderson, Pool

This year's primary election cycle has seen plenty of blowouts, but that's not stopping some Republicans from crying fraud. GPB's Stephen Fowler reports.

Kandiss Taylor, a Georgia Republican gubernatorial candidate, participates in a Republican primary debate on Sunday, May 1, 2022, in Atlanta.

When Gov. Brian Kemp overwhelmingly won the Republican primary in Georgia on May 24, his chief opponent, former Sen. David Perdue, was quick to admit it was over.

“Everything I said about Brian Kemp was true, but here's the other thing I said was true: He is a much better choice than Stacey Abrams,” he said shortly after polls closed. “And so we are going to get behind our governor.”

But another one of his opponents felt something was off.

“I want y’all to know that I do not concede,” Kandiss Taylor said in a video posted to social media. “I do not. And if the people who did this and cheated are watching, I do not concede.”

Kemp won Georgia’s primary with about 74% of the vote. Perdue, who had the backing of former president Donald Trump, earned about 22% of the vote.

And Taylor? Just 3.4%.

Taylor is a fringe figure in Georgia with a history of making false claims about the 2020 election, voting machines and how elections are run. In the days following her defeat, Taylor has asked followers to sign affidavits stating they voted for her to prove she won the election — despite no evidence the vote totals are incorrect and with the deadline to challenge an election already passed.

A number of other primary candidates sent letters asking for hand recounts of their contests and alleged fraud, but state and local officials rejected those claims. Perpetual election denier Garland Favorito and his VoterGA organization filed a lawsuit challenging Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger's victory in all 159 counties, but missed also missed the deadline for an election contest and is missing actual evidence of wrongdoing.

Taylor's quest to prove she won a race in which voters deemed her irrelevant is not an outlier, but rather an indicator of a new crop of candidates who insist they won their elections, regardless of the facts.

While Trump has most notably spent the last 18 months denying his 2020 election defeat, despite clear evidence he lost, he’s not the only one. During this election cycle, candidates across the country have refused to concede — even in races that are not remotely close.

Last week in Colorado, a county clerk — who has been indicted on charges including election tampering — finished last in the GOP secretary of state primary. But she's refused to acknowledge her loss and accused officials of cheating.

“We didn’t lose; we just found more fraud,” Mesa County clerk Tina Peters told supporters at an election night party.

In South Carolina, a pair of Republican primary challengers said their blowout losses were tainted by serious problems.

Both gubernatorial candidate Harrison Musselwhite and attorney general candidate Lauren Martel lost by double digits against popular incumbents and both sent nearly identical letters to state officials claiming a plethora of concerns with the election. The South Carolina Republican Party’s executive committee rejected the claims.

And in Nevada, GOP gubernatorial primary runner-up Joey Gilbert told supporters in a video message he could not have been defeated.

“It is impossible for me to concede under these circumstances,” he said. “I owe it to my supporters. I owe it to all Nevadans of all parties to ensure that every legal vote is counted legitimately.”

Gilbert, who was outside the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, has paid close to $200,000 for all 17 counties to recount the governor’s race, which he lost by about 11 percentage points. State and local officials reject Gilbert’s claims.

In all of these cases, there is no evidence to back up claims of fraud that could reverse defeats, and most of these elections were not remotely close. But Matthew Weil with the Bipartisan Policy Center says unfortunately, that doesn’t matter to those who push the narrative of fraud.

“There is a very strong segment of the electorate that believes strongly if their candidate had lost, and they were doing well in the polls — even if they weren't doing well in the polls — it was the election machinery that caused their loss,” he said.

The vast majority of elections end uneventfully, even in close races, but a recent incident in New Mexico shows how election denialism is affecting local election procedures.

Commissioners in rural Otero County gained national attention for initially refusing to certify the results in the Republican-heavy area. After pressure and threat of legal action, of the three commissioners, only Couy Griffin voted no.

“My vote to just remain a 'no' isn't based on any evidence,” he said at a June 17 emergency meeting. “It's not based on any facts; it's only based on my gut feeling and my own intuition and that's all I need.”

Griffin called into the meeting from Washington, D.C., where he was sentenced for his role in the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection.

It’s not just fringe candidates making these claims, either. An NPR investigation tracked four election conspiracy influencers across hundreds of local events in 45 states and the District of Columbia, including meetings with at least 78 elected officials across all levels of government.

These sitting lawmakers can have power to shape legislation that alter voting laws and can make it harder for people to vote and easier to subvert results.

Weill said you also don’t have to look far to see why losing candidates could benefit from ignoring electoral reality.

“There are clearly now perverse incentives for losing candidates to keep up the fight long after the certification is complete and they’ve lost,” he said. “And those incentives are that they can raise money for these challenges [that] often don’t cost much because there’s nothing to them, and they can use that money in future cycles.”

The biggest example of fundraising off of a message of fraud might come from Trump himself. He raised more than a quarter billion dollars to cover legal fees during his attempts to overturn the 2020 election for an election legal defense fund.

But the House committee investigating January 6 said that money went to organizations aligned with Trump instead.

Voting experts and elections officials are worried this behavior will only increase in future elections, especially in battleground states where some elections aren’t decided by such wide margins.