Section Branding

Header Content

Georgia Today: The three death sentences of Clarence Henderson

Primary Content

In 1948, a Black sharecropper in Georgia was sentenced to die for a murder he didn’t commit. What happened next tells us a lot about the legal system in the United States then — and now.

RELATED: Bookshelf: Unsolved murder in 1948 Carrollton subject of new book

Chris Joyner, author and investigative reporter, Atlanta Journal-Constitution: This was a family history that was entirely lost. If I could do nothing else, if I could provide this kind of history to Clarence Henderson's family to show that he was an innocent man who was tried and convicted three times in an unjust court, if I can provide that for his family, I feel like I did a pretty good job.

Steve Fennessy: This is Georgia Today. I'm Steve Fennessy. On the show this week, a piece of history from the middle of the last century that, in some ways, could have been written a lot more recently. It's the story of a Black man sentenced to death for murder not once or even twice, but three times in a small Georgia town. He insisted he was innocent. What happened next tells us a lot about the legal system in the United States, not just then, but where we are today. My guest is Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigative reporter Chris Joyner. Chris has written a book called The Three Death Sentences of Clarence Henderson: A Battle for Racial Justice at the Dawn of the Civil Rights Era. Chris joins me now. Welcome, Chris.

Chris Joyner: Thanks, Steve.

Steve Fennessy: So, Chris, your book pivots around a murder that occurred on Halloween night in 1948 in Carroll County, which is about, what, 45 miles or so west of Atlanta? So what happened exactly that night?

Chris Joyner: A young man — his name was Buddy Stevens; he went by Buddy — he and his date Nan Turner were out at a sort of lover's lane area that evening, and they were abducted by a masked man with a gun, marched over several fields and over fences. And at one point, the man — the masked man — attempted to rape Nan, but he fought for her as she ran and was shot to death.

Steve Fennessy: So she ran away, and while she was running away, Buddy was shot.

Chris Joyner: Exactly. And the community there later found out there had been a serial rapist working in the area over the course of the summer and fall of 1948. No one had a good description of the assailant because he was always masked and took great pains to sort of conceal his identity. So it was a real whodunit when Buddy Stevens was killed.

Steve Fennessy: Well, what more can you tell us about Buddy Stevens? How old was he and where did he come from?

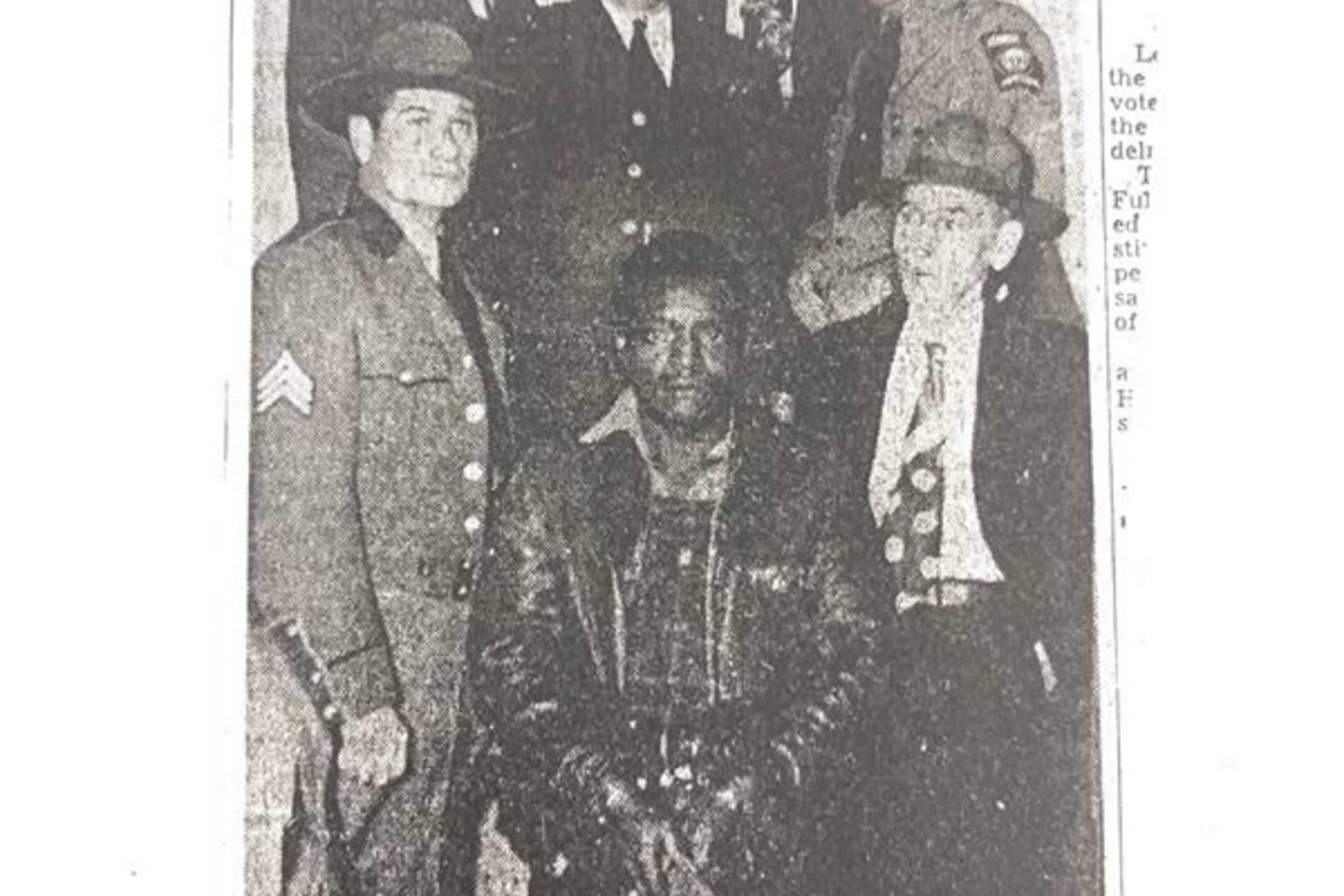

Chris Joyner: Buddy was 21. He and his family were prominent in Carrollton, which is the county seat of Carroll County. And he had recently returned from some military service overseas. He served in the immediate post-World War II period in the army as a military policeman, and he was a student at Georgia Tech at the time. He had come back for a date with Nan, who was a local teenager and beauty pageant winner there in Carrollton. One of the things that was so shocking for the community, apart from the sort of random violence, was that Buddy was really seen as one of those sort of bright lights of the community there.

Steve Fennessy: Talk a little bit about Carroll County itself. I mean, today it's essentially, effectively kind of a suburb of Atlanta. But back in 1948, it was a different place.

Chris Joyner: It was. It was much more isolated, not as connected to certainly not as connected to Atlanta. But like a lot of communities after World War II, it had really high hopes for what it could become. Carrollton and Carroll County really saw itself as a progressive community in the period. There was a university there. There were large employers. There were residential developments that were going on there. You know, it was a community that very much was poised to grow in this post-World War II period.

[News tape] Study.com: With the dramatic increase in new families, suburbs emerged as a popular place to live. These prefabricated homes placed just outside city limits became all the rage.

Chris Joyner: The death of Buddy Stevens was so shocking because it really seemed to threaten what Carrollton saw it could become.

Steve Fennessy: So Nan is running away. What happens next?

Chris Joyner: Nan runs to the nearest house, which is about a half a mile away. Buddy was shot on what would become the Sunset Hills Country Club golf course. And at that time, it was all rough field, and so she ran to the nearest house, where the police were called. The only description she could give of her attacker was that he sounded like he was Black. She never saw him. He was masked. It was a new moon. It was also overcast and raining, so it was very dark out there. Like in a lot of these cases that occurred before, there was no solid information on who the assailant was. But the police immediately narrowed in on looking for a Black suspect. And of course, that also fed into common tropes about Black men and their relationship with whites in the South and across the nation for generations. Fear was a really powerful trope that led to a lot of lynchings.

[News tape] PBS NewsHour: The practice of racial lynchings: executions of African-Americans done outside the judicial system and often intended to subdue Black communities into passivity.

Steve Fennessy: And so, in 1948, police hear that the suspect may have been Black. So what do they do next?

Chris Joyner: There's a massive manhunt. It goes well beyond Carroll County, and lots of Black men were captured and held — in secret, really — and questioned until they came up with, first, one suspect who was indicted and very nearly tried on that charge, before they moved on to Clarence Henderson. And this was — would have been like 18 months later. They connected him to what they believed was the murder weapon.

Steve Fennessy: How did they find the murder weapon?

Chris Joyner: It's a really extraordinary story about the murder weapon. It was a .38 Special police revolver and it was found in a pawn shop on Marietta Street in downtown Atlanta. It had been reported as stolen and investigators believe they could put the the gun in Clarence Henderson's hands for a very narrow window that would have been enough to have committed the murder with it. The only problem was that it was a .38 revolver, and the the bullet that was extracted from Buddy Stevens' body was a 9 mm automatic.

Steve Fennessy: Doesn't that rule him out then?

Chris Joyner: You would think so. But this was a really early period of using forensic ballistics in criminal trials, and we had a new — it would eventually become the state crime lab. But at the time it was — it was under Fulton County police.

Audiobook, The Three Death Sentences of Clarence Henderson: Around the same time, the identification bureau began upgrading its equipment and methodology. At the time an Atlanta Constitution article trumpeted the county's latest step in the march toward scientific crime detection with the purchase of a photostatic machine that can make copies of fingerprints to send the FBI in Washington. With this, the paper reported, the bureau had outdistanced any other identification bureau in the South.

Chris Joyner: And the preliminary ballistics showed that although it was an automatic — 9 mm automatic bullet, it had been scored in a way that indicated it came from a .38 revolver and it caused a lot of problems. They had to sort of reverse engineer to how that had happened because a 9 mm shell will not chamber in a .38 revolver; it's too wide. And then they solved the problem — that the bullet that killed him was a 9 mm — by saying that had been filed down and made to fit a .38 revolver.

Steve Fennessy: Who is Clarence Henderson?

Chris Joyner: Clarence Henderson was a sharecropper in Carroll County. He was a rough person. Carroll County was a dry county and he moved liquor through the county. He was a gambler. He was known to fight. He was not particularly well-liked among some people in his own community. So he made sort of a convenient suspect in that way, in that he had a criminal record, even though he had no connection to Buddy Stevens. No reason to be in the Sunset Hills Country Club area. At that time, he had no car, so it would have been difficult for him to get there. And it's hard to imagine a Black man moving through white Carrollton in lovers' lanes areas unnoticed. But nonetheless, he was the suspect they came up with.

Steve Fennessy: He was married, correct?

Chris Joyner: He was married. He had a wife and two children and a third on the way.

Steve Fennessy: What did his wife say about where he was that night?

Chris Joyner: He had an alibi. I mean, his alibi was that he was home with his wife at the time. But in the first trial, his court-appointed defense attorneys didn't provide, really, a defense. They called no witnesses — not his wife, not anyone that knew him. They made very few objections to the prosecution. He had to local white attorneys, and the only defense they put up was an unsworn statement. Henderson himself went to the stand, made a statement, and that was his only defense. That first trial lasted one day, and he was found guilty and sentenced to the electric chair. The jury was all white. The grand jury was all white. In fact, every jury that he would face would be all white.

Steve Fennessy: So he's found guilty. He's sentenced to death. This is kind of routine justice at the time. Why is this taken up on appeal?

Chris Joyner: Well, certainly it was routine that Black men would face quick trials and harsh punishment during this period, particularly when the victim was white. And part of it was sort of commonly held racial beliefs during the period that Black men were especially threatening, particularly to white women. I would say, in some ways, it was unusual that Clarence Henderson made it to trial at all. Often, Black men accused of such crimes would not see the inside of a courtroom. They could be lynched.

[News tape] PBS NewsHour: Many of these acts of terror took place on courthouse lawns, in front of schools, in front of churches, in front of places that still exists today.

Steve Fennessy: So Clarence Henderson is convicted, sentenced to death. So who takes up his cause when it comes time to appeal?

Chris Joyner: After that first trial and the verdict were carried on by The Associated Press and also in Black-owned newspapers, It came to the attention of the Black legal community in Atlanta, as well as the Communist Party, which was very interested in representing Black men accused of crimes against white people. They saw that the subjugated class for African-Americans, they felt, that communists could go and recruit people for socialist revolution through African-Americans. It came to their attention first and then later to the NAACP.

Steve Fennessy: So did the NAACP welcome the collaboration of the Communist Party?

Chris Joyner: Absolutely not. The NAACP during that period was very concerned about being painted as friendly to communist influences. So when the Communists got involved in defending Clarence Henderson, the NAACP pulled back and refused to support it unless the Communists were disavowed by Clarence Henderson, which Clarence Henderson eventually did. And the NAACP then moved in and provided the support for his first appeal and his second trial.

[News tape] Zinn Education Project: The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, had been founded in 1909 in response to the rising tide of racial violence.

Steve Fennessy: So he gets his appeal. He gets a second trial. What's the second trial like?

Chris Joyner: Remarkably different than the first one. First, he wins on appeal in the Georgia Supreme Court, represented by two Black attorneys from the Sweet Auburn district. And that in itself is a sort of landmark that he's convicted of — of murder and is overturned on lack of evidence at the Supreme Court and remanded back for a second trial. The second trial goes on several days — also not only unusual just in the case of a Black man accused of killing a white man, but unusual in that it was a thorough defense. Not only did the two Black attorneys provide the defense, they also hired a former state prosecutor named Dan Duke, a white man who was amenable — in fact, very interested in representing Black people in white courtrooms. And he provided sort of the white face of the defense for that jury.

Steve Fennessy: So Duke and the two attorneys from the NAACP mounted a vigorous defense of Clarence Henderson, but still resulted in yet a second conviction.

Chris Joyner: He would be convicted again. They did return a verdict of guilty, but no recommendation for mercy. And he was again sentenced to death.

Steve Fennessy: And it's appealed again. What's the basis of these appeals that the Supreme Court of Georgia is saying he needs to be tried again; he didn't get a fair shake?

Chris Joyner: The Georgia Supreme Court remained unconvinced that the evidence against Henderson supported his conviction. I think it goes to show sort of the tenuous nature of the state's case against Henderson during this period. But it also shows how desperate that community was to find a culprit for Buddy Stevens' murder. That they would — they would try and convict Henderson on purely circumstantial evidence.

Steve Fennessy: He's convicted and sentenced three times. What ultimately happened with him?

Chris Joyner: He's never acquitted. But when it's remanded back for a third trial, the case is placed on what's called the dead docket, meaning that it was officially open but not being pursued.

Steve Fennessy: How legwork and some luck led Chris Joyner to the case file that resulted in his book. That's next. This is Georgia Today.

[BREAK]

Steve Fennessy: This is Georgia Today. I'm joined by Chris Joyner. Chris, you're an investigative reporter at the AJC. What led you to this story to begin with?

Chris Joyner: Well, you know, it's funny. I started my career in the late 1990s at a small newspaper in Carrollton, Ga. The Times Georgian, which was — it was my very first newspaper job. I had gone to West Georgia as an undergraduate, as had my parents. And when I got a job at the Times Georgian in Carrollton, my father said that I ought to go to the archives of the paper and look up the death of Buddy Stevens. Dad had gone to school in the 1940s at West Georgia and remembered the murder, and he said, "I don't think anybody ever was found guilty of that." So I pulled down one of the bound volumes of the 1948 Georgian and started looking at it. And I was just amazed at the twists and turns of the story, but also at how affected the community was. And I got really interested in that part of the story. It was such a traumatic event for Carrollton.

Steve Fennessy: We think about 1948 post-World War II America as a time of optimism, and it was leading into the 1950s, the Eisenhower years. And this idea of progressivism of America sort of asserting its dominance on a world stage just because we went to war doesn't mean that necessarily things are changing at home. Tell me a little bit more about some of those changes that were happening in Carroll County and to what degree maybe they reflected changes that were going on in society at large here.

Chris Joyner: It was a very complex period.

Audiobook, The Three Death Sentences of Clarence Henderson: Allied victory had rescued humanity from a dark future. But for President Truman and his administration, the celebrations were short-lived. There were still a number of challenges that remained, including the demobilization of millions of men and women reshaping the economy without putting millions out of work, social unrest and growing racial tensions at home.

Chris Joyner: There was a lot of pent-up energy from the Depression and the war and the — and the desire of communities to move ahead and move forward. Carrollton was very much like that. It really saw a — real opportunities to better itself and become a really sort of, you know, sort of a shining city on a hill kind of vision for itself. At the same time, there was a lot of social change that was happening during this period. We see the beginnings of a racial reckoning that would occur throughout the civil rights movement. It was also the period of the Red Scare.

[News tape] The National WWII Museum: And the looming threat of the nation's burgeoning rivalry with the Soviet Union.

Chris Joyner: There was a real concern that the institutions, the democratic institutions of America, were threatened, and for a community like Carrolton, you throw a murder in the middle of that and it just exacerbates those — those tensions. That's why it was such a big deal when Buddy Stevens was killed and there was this mix of race and sex in the murder. It became a really defining event.

Steve Fennessy: I imagine it would be very difficult to overstate how different the experience of being a Black resident of Carroll County was compared to being a white resident.

Chris Joyner: Absolutely. And you can expand that into Atlanta as well, where the Black community, many of them had had served in World War II and came home expecting a greater degree of freedom and equality.

[News tape] The National WWII Museum: Black veterans returned home to the promise of a new life, only to find they were still living under the same white supremacist laws that had prevented them from entering neighborhoods, universities and job markets as before the war.

Chris Joyner: The arrest of Clarence Henderson became a cause celebre for that community because they saw it as emblematic of this injustice that they had been experiencing generation upon generation. Thurgood Marshall, who would become Supreme Court justice, was head of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund during that period and became involved in the defense of Clarence Henderson because he saw these cases as important, moving ahead from segregation, and they were working on two tracks at the NAACP. One was on trying to dismantle the legal system of segregation, and the other was defending Black men across the nation against these sort of crimes where, you know, the evidence just did not support that they did it.

[News tape] The National WWII Museum: A legal challenge to the Jim Crow laws would require a cadre of young Black lawyers armed with a zeal for social justice.

Steve Fennessy: Chris, as you were researching and writing this book, our country was going through a modern-day reckoning. What parallels or connections did you see between what you were looking up from, you know, 70 years ago, versus today?

Chris Joyner: There are a lot of parallels. I mean, a lot of the themes that we see in immediate postwar period in America are those that dominate the next, you know, 70 years. How is our society going to address the idea that our justice system does not operate the same for everyone? How are we going to deal with historic inequities and their effect that they have today on marginalized communities? And also can our democratic institutions survive what we're going through, either from our own internal conflicts or interference from outside of our borders? It's one of the reasons why I think the story, although it's about a murder in a small town 70 years ago, I think it has a lot of resonance today.

Steve Fennessy: One of the things I found really compelling about your book was the level of detail, especially when it came to the court scenes. How, in a case that occurred 70 years ago or so, did you manage to find that?

Chris Joyner: When I started doing the research, when I was a young reporter, I was relying largely on newspaper clips and it was, you know, it was heavily covered during that period. But there's a limit to what you can get out of the newspaper page. When I picked the research up here in recent years — because I did set it aside for 15, 20 years and didn't really touch it and only went back to it about five or six years ago — I realized I had a lot more research to do. One of the things that I needed were the court transcripts, so I made a trip to Carrollton. And when I got there, they let me wander the — the stacks, you know, go back into the archives because it was such an old case. And what I found was they were all missing.

Steve Fennessy: So there goes the book.

Chris Joyner: And there goes the book. Exactly. I'm not going to be able to write the kind of book that I want to write, the level of detail that I really wanted to get into without those transcripts, and they were just plain missing. There was the case before, in the case after and just a missing tooth where those transcripts should be. I started making phone calls. I found a book that was a biography of the founder of the Georgia Crime Lab, which referenced the case — the Henderson case — and I called that author and asked him because he seemed to be quoting from transcripts — and transcripts I didn't have. And he said, 'Well, I was able to go to the courthouse and look at 'em, but that was the old courthouse.' Carroll County, in the interim, had built a new courthouse. I ended up contacting a district attorney's investigator who had retired, but had helped that author find those transcripts back then. And she said when she had found them — in the early '00s, I guess — they had been in the evidence room in the old courthouse because, technically, the case is still open. I contacted the clerk courts and I said, 'I don't know whether this helps or not, but in the old courthouse, they were in the evidence room.' Well, he called me 10 minutes later. He said, 'I've got 'em; I've got them all and I've got the gun. I've got the bullet that was extracted from Buddy Stevens. I've got prosecution exhibits,' he said, 'but it's been sitting on a shelf for 15 years.' That was a real breakthrough that really allowed me to get the kind of depth of detail that I was able to get for these trials.

Steve Fennessy: And you say this case is still open, so that means that no one was ever prosecuted or convicted of this crime?

Chris Joyner: No one was ever prosecuted. It was a fatally flawed investigation. From the moment Nan Turner said she thought her attacker sounded Black, the investigation was essentially doomed. Once they had a suspect, essentially, they stopped looking. It was incredibly destructive to the Henderson family and would be for generations. One of the conversations, obviously, we're having right now, is how do we talk about generational racism? I've been in contact with the descendants of Clarence Henderson, and they will tell you it was a traumatic event that impacted his children and his children's children. They were sharecroppers in 1948. They were poor then and disadvantaged then. And then you add the weight of three trials and years of imprisonment — because Clarence Henderson was not allowed bond, he was in prison during this whole period. It took a family that was on the edge and pushed them over. And this kind of rough justice that occurred across the nation during this period had impacts on families everywhere.

Steve Fennessy: What's been the reaction of some of the descendants of the people that you portray in the book?

Chris Joyner: Well, very emotional. I mean, I've spoken and been with one of his grandsons. The very first time was when I showed up in his front yard and said I wanted to talk to him about his grandfather.

Steve Fennessy: And this is Clarence Henderson?

Chris Joyner: Exactly. And I had brought my a lot of my research with me to show him. By the end of about a half hour of explaining what I had, he was in tears because, you know, this was a history, a family history, that was entirely lost. If I could do nothing else, if I could provide this kind of history to Clarence Henderson's family to show that he was an innocent man who was tried and convicted three times in an unjust court, if I can provide that for his family, I feel like I did a pretty good job.

Steve Fennessy: My thanks to Chris Joyner. His book, The Three Death Sentences of Clarence Henderson: A Battle for Racial Justice at the Dawn of the Civil Rights Era, is published by Abrams Press. Eagle Eye Bookshop in Decatur will host Joyner for a discussion about the book on Tuesday, March 8 at 7 p.m. Georgia Today is produced at Georgia Public Broadcasting by Jess Mador. Our engineers are Jesse Nighswonger and Jake Cook. You can keep up with Georgia Today by subscribing to the show wherever you get podcasts. Thanks for listening. We'll see you next week.