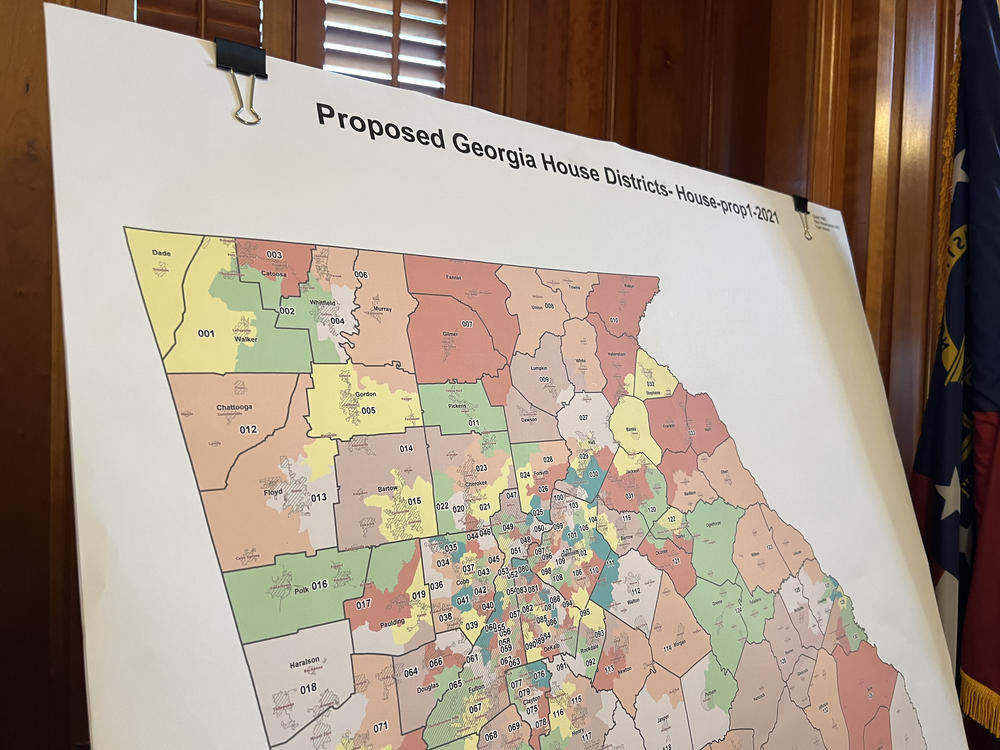

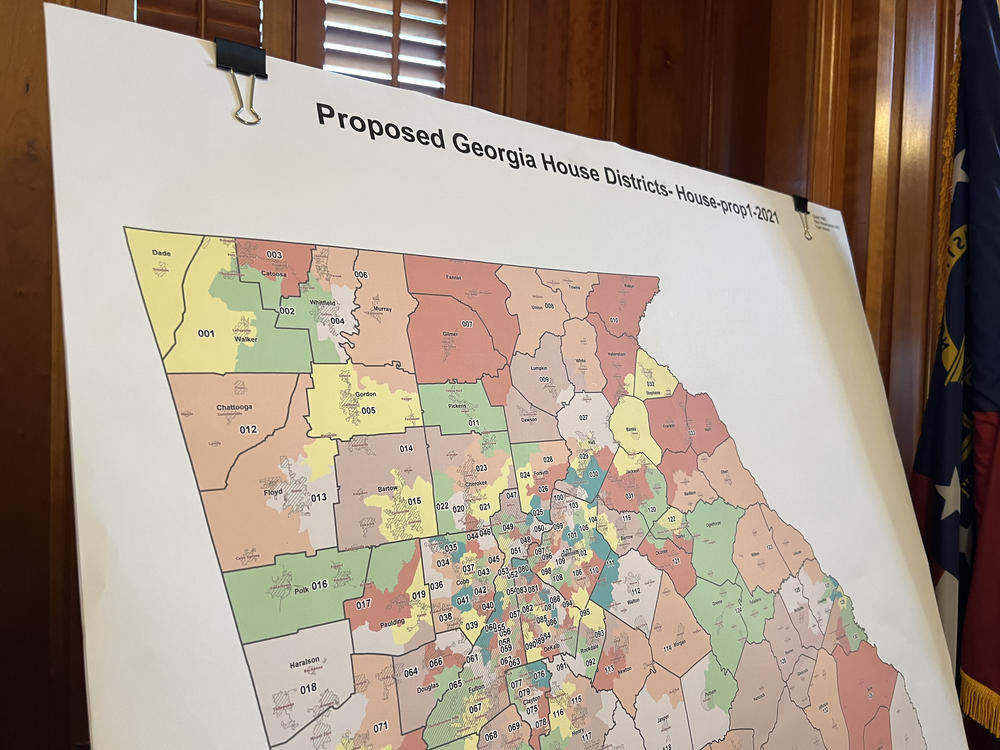

Caption

A proposed map of Georgia's 180 state House districts sits outside the chamber before lawmakers approved it on a mostly party-line vote in 2021.

Credit: Stephen Fowler / GPB News

A proposed map of Georgia's 180 state House districts sits outside the chamber before lawmakers approved it on a mostly party-line vote in 2021.

It did not take long after the proverbial ink to dry before lawsuits were filed against Georgia's new political redistricting maps covering the state House, state Senate and U.S. House district boundaries.

Gov. Brian Kemp quietly signed the new maps into law Thursday, Dec. 30, 2021, after a special legislative session that ended in November, codifying Republican dominance in a state that has seen a rapid political and demographic shift toward Democrats.

Despite flipping both U.S. Senate seats in January and electing President Joe Biden last November, Georgia's congressional delegation will actually gain a GOP-favored seat under the new law. And while the state legislative maps cede more seats to Democrats in metro Atlanta, Republicans will still have a comfortable majority in both chambers.

MORE: How Georgia's redistricting process sets the playing field for 2022 and beyond

While statewide elections have essentially been a competitive 50-50 split in the last four years, the new districts approved for state and federal lawmakers are not as competitive, possibly leading to more races being decided in lower-turnout primaries and the potential for more extreme candidates to take office.

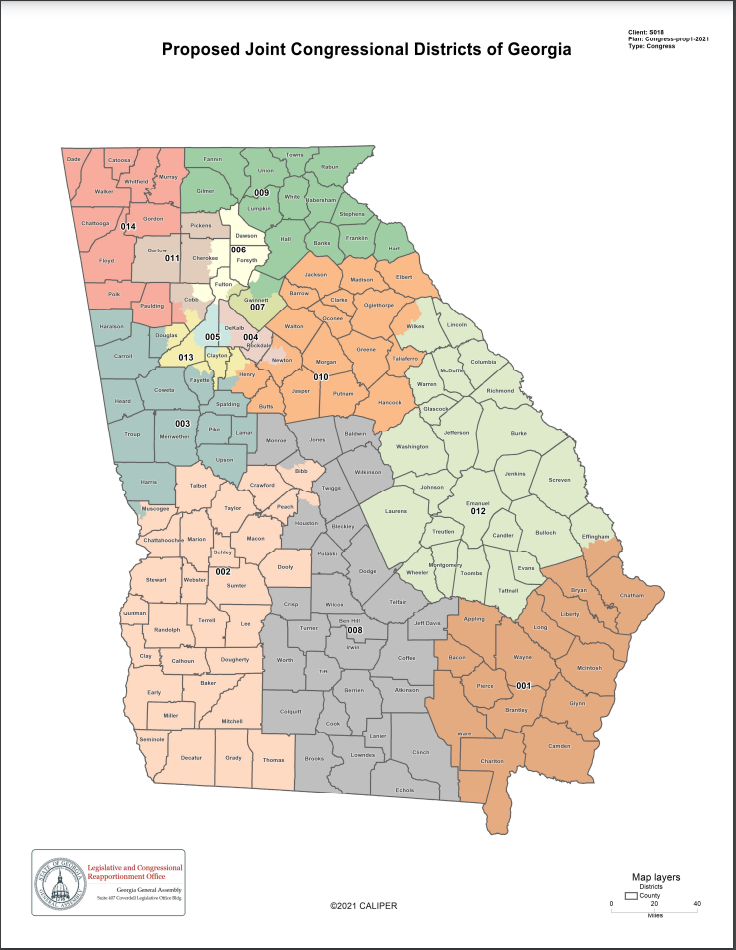

Georgia's current U.S. House delegation has eight Republicans and six Democrats, but a dramatic overhaul to the 6th and 7th districts in Atlanta's northern suburbs will likely result in nine Republicans after the 2022 midterm elections.

The new congressional map takes the 6th District, represented by Democrat Lucy McBath, and turns it into a conservative stronghold by moving the seat northward to include Cherokee, Forsyth and Dawson County voters. In turn, the 7th District represented by Democrat Carolyn Bourdeaux shrunk its footprint to just part of Gwinnett County and Johns Creek, creating a safely Democratic district.

A lawsuit filed by five Georgia voters from Cobb and Douglas counties says the area's Black population growth over the last decade is significant enough to have a congressional district based there. The two counties are currently split between five different districts.

"Rather than draw this additional congressional district to allow Georgians of color the opportunity to elect their preferred candidates, the General Assembly instead chose to 'pack' some Black voters in the Atlanta metropolitan area and 'crack' other Black voters among rural-reaching, predominantly white districts," the filing reads.

Data shows, on average, a Republican congressman from Georgia would win with 61% of the vote in their district while a Democratic representative would need to capture 72% of the vote, meaning districts with Democratic U.S. House members have Democrats more heavily packed into them than Republicans are in Republican districts.

The latest Census data shows Georgia's Black population has grown nearly 16% in the last decade and makes up a third of Georgia's 10.7 million people, while the share of white residents has declined and the state is on track to be majority nonwhite in the near future.

The state Senate map moves two rural Republican districts into Democrat-heavy metro Atlanta areas while shifting the boundaries of Democratic Sen. Michelle Au's Johns Creek-based district to become conservative-leaning and majority white. An analysis from the Princeton Gerrymandering Project finds only one of the 56 new districts is competitive.

In the state House, Republican mapmakers utilized several retirements in more rural communities to jettison several seats of their majority and create Democratic-leaning seats in Cobb, Fulton, Gwinnett and Rockdale counties as well as a new seat in conservative-leaning Forsyth County.

The ACLU of Georgia filed a lawsuit on behalf of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, the Sixth District African Methodist Episcopal Church and several Georgia voters arguing those maps violate the Voting Rights Act by diluting the strength of Black Georgians.

"The southern Atlanta metro region has seen explosive growth in the Black population over the last decade, and yet the new districts fail to allow those new Black voters to elect candidates of their choice," Sean J. Young, legal director of the ACLU of Georgia, said in an interview. "For example, Senate districts 16 and 17 in the south Atlanta metro region only have about 25-35% Black voters, when several of the counties in those districts' Black population have grown by well over 30-40%. So politicians cannot just try to freeze Black political power as if it were still 2010."

Georgia as a whole has grown by more than 1 million people in the last decade, almost exclusively by adding nonwhite residents in the metro Atlanta area, and political power has shifted away from rural, white Republicans. The legal challenges say that reality is not reflective of the political maps that, barring the success of any lawsuits, will govern the state for the next decade.

A third suit filed by the Georgia NAACP, Georgia Coalition for the People's Agenda and GALEO is the most extensive, naming dozens of districts across the three maps that they say violate the Voting Rights Act as well as the U.S. Constitution.

"Had the chosen map drawers and the Georgia General Assembly drawn districts that accurately reflect Georgia's increasingly diverse population without the improper consideration of race, opportunities for people of color to elect candidates of their choice would have necessarily increased," the filing reads.

All of the lawsuits ask the federal courts to compel the legislature to draw new maps that better reflect Georgia's demographics. The NAACP challenge wants a panel of three federal judges to take further steps and require Georgia to preclear its voting changes with the federal government, a status that the state and other jurisdictions with a history of racist voting changes had under the Voting Rights Act of 1965 until the U.S. Supreme Court's 2013 Shelby v. Holder decision.

While these cases can take time to untangle, preparations are already underway at the local level for elections officials to sort voters into their new districts in time for the May primary elections — though the association of local elections officials has asked lawmakers to delay the primary a month to provide more time to complete the redistricting process.