Section Branding

Header Content

Federal Appeals Court Hears Arguments On Georgia’s Restrictive ‘Heartbeat’ Abortion Ban

Primary Content

The U.S. 11th District Court of Appeals heard oral arguments on Friday in the case of Georgia’s controversial law HB 481, also known as the “heartbeat bill” because it would ban abortions after a doctor can detect a fetus’ heartbeat.

But judges were wary to push the case forward as the U.S. Supreme Court is set to take up Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, a case from Mississippi that bans most abortions after 15 weeks.

Georgia’s law under constitutional review would ban most abortions once a doctor could detect fetal cardiac activity — usually around six weeks of pregnancy. Critics say many women don’t even know they are pregnant until further into the first trimester, meaning the law essentially amounts to a total ban on abortions.

The restrictive Georgia law is on par with the recently enacted Texas law, which also bans abortions as early as six weeks and has stirred outrage among supporters of reproductive rights.

Friday’s hearing also played out at the same time the U.S. House passed legislation that would create a statutory right for health care professionals to provide abortions — a move that comes amid the intensifying battle over abortion rights.

Judge William H. Pryor Jr. questioned attorneys on both sides about the feasibility of moving forward with the case while the Supreme Court’s decision in the coming months would set a legal precedent.

“If it were to uphold that law, that would really require us to think hard about how the Supreme Court's decision applies here,” Pryor said.

“I think that's the prudent way to proceed,” he added. “Don't you agree, though, that's really what we ought to do? I mean, it's not every day that we get the Supreme Court — actually, we can allow the Supreme Court to do some work for us.”

Both the state’s attorney and plaintiffs acknowledged the potential precedent-setting significance of the Supreme Court’s upcoming decision.

The ACLU of Georgia and a coalition of abortion rights activists sued the state in 2019 after lawmakers passed HB 481, which creates a short timeline for a woman to receive an abortion. It also includes what supporters call “personhood” language that grants legal rights to fertilized eggs.

The law was blocked in lower courts, preventing it from being enacted. Mississippi’s law was also blocked by lower courts, but is now set to challenge a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion upheld by Roe v. Wade.

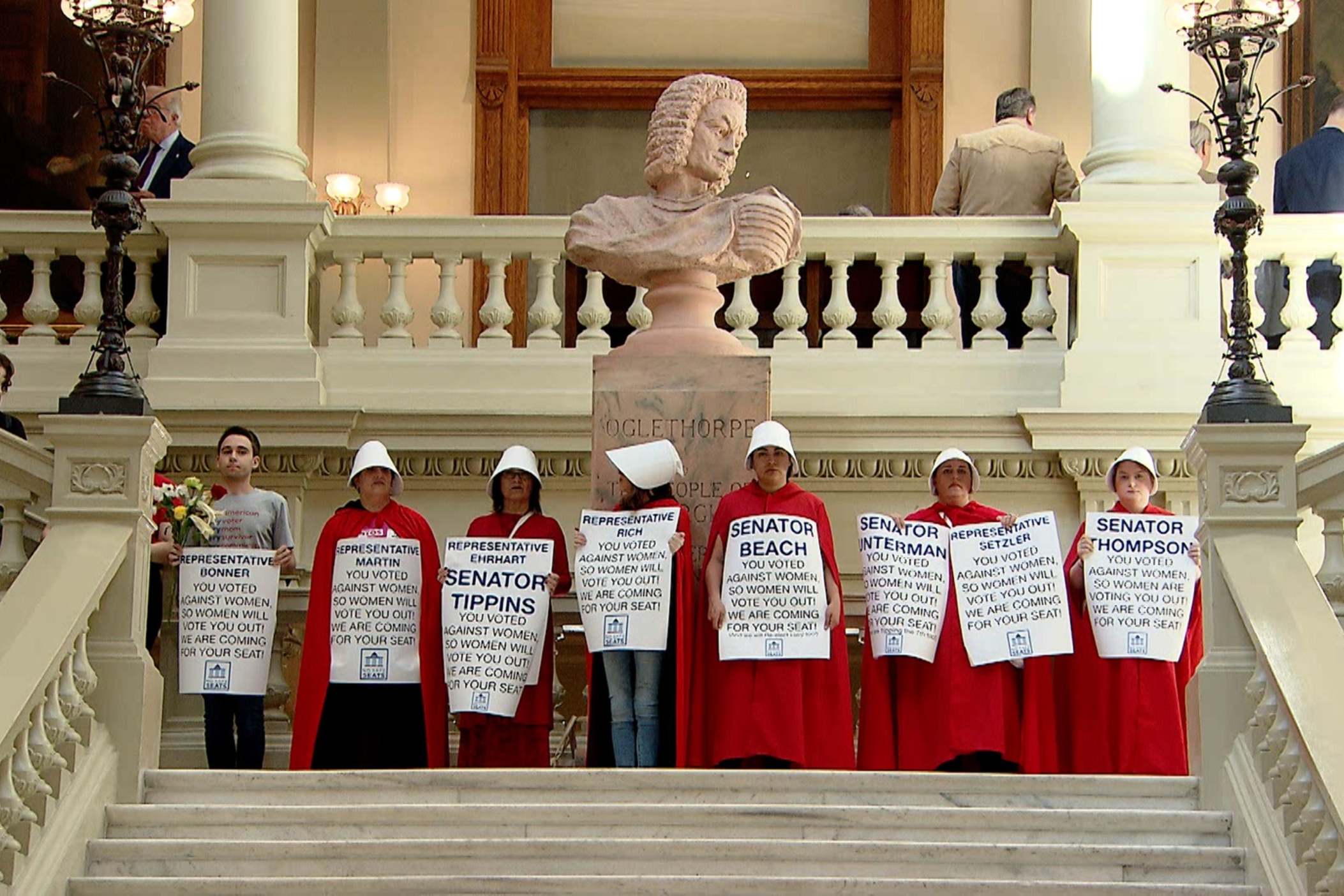

Georgia’s bill sparked outcry from abortion rights advocates who have called it a direct attack on women’s rights by Republican lawmakers.

“This case is about letting ‘her’ decide,” Sean Young, legal director for the ACLU of Georgia, told GPB News. “Letting women decide for themselves when to start or expand a family and letting women make their own health care decisions.”

Attorney Jeffrey Harris, arguing for the state, argued that there are provisions aside from the strict abortion limitations that would positively impact Georgia women.

“The Georgia legislature passed common sense fetal well-being provisions,” he argued, “including one that would make absent fathers pay child support during pregnancy and another that would give valuable tax benefits to pregnant women.”

The ACLU argued that no provision of the law should be upheld if one aspect is found unconstitutional.

“Under Georgia law, if there is a law that is unconstitutional, and other provisions of the law are really just a kind of scaffolding for the central purpose of that law, then those other parts of law should fall away as well,” Young said.

Subasri Narasimhan, professor of public health at Emory University, has studied the bill from its introduction under the Gold Dome to its journey in the court system.

On GPB’s Political Rewind, she said “ideologically motivated abortion restrictions,” like Georgia’s law, can cause significant harm to women, particularly low-income and women of color.

“There’s a lot of unknown when we think of these kind of severely restrictive abortion bills,” she said. “But what we can say is that bills like this are really a human rights violation. Making someone carry a pregnancy they’re unprepared for or they do not desire, it’s basically the antithesis of reproductive justice and a serious human rights violation.”

“There’s no medical or scientific basis for bills like this,” she added. “And there’s no upside to it either for the state of Georgia.”

Georgia’s six-week abortion ban is still blocked pending litigation.

It was not immediately clear when the federal appeals court might make its decision, except the justices seemed likely to wait until the Supreme Court first rules on the Mississippi case, which is not expected until next summer.