Section Branding

Header Content

How Georgia’s Redistricting Process Falls Short on Transparency

Primary Content

This is Part 2 of a two-part story on redistricting. You can read Part 1 by clicking here.

Throughout recent redistricting hearings held across Georgia, residents around the state have stepped forward to call for improved insight into the once-a-decade recasting of Georgia’s political boundaries and greater opportunity for public input.

While Georgia’s redistricting process is inherently partisan, there are measures that experts say can be employed to make the process fair and transparent.

In 2011, the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonpartisan law and policy institute, issued a Media Guide to Redistricting that laid out a series of criteria by which journalists can assess the redistricting process in their states.

These included issues such as whether mapmakers have a personal stake in the outcome of the process, the partisan and demographic makeup of the mapmaking body, the degree of public access to data and materials used in drawing maps, opportunities for the public to have meaningful input in the process and whether there is a process for holding mapmakers accountable.

Using these criteria as benchmarks, it is possible to gauge the transparency of a state’s redistricting system.

A Georgia News Lab/GPB News review finds Georgia falls far short.

Here is what we found:

Do mapmakers have an interest in the outcome?

In Georgia, lawmakers on the state House and Senate redistricting committees have a hand in drawing the lines of their own districts, although in practice the majority party controls the process.

Each committee approves the district boundaries for its own chamber, aided by the Legislative and Congressional Reapportionment Office (LCRO) which provides data analysis and renders the maps. The two committees jointly approve congressional districts.

In addition to protecting the interests of their respective parties, lawmakers on the committees also have an interest in safeguarding their own seats. That is especially true this year, as several members of each committee represent districts that are undergoing rapid political and demographic shifts, making it increasingly difficult for Republican incumbents to prevail.

For example, Georgia House redistricting committee chair Rep. Bonnie Rich (R-Suwanee) represents House District 97 in fast-growing and rapidly diversifying Gwinnett County. Once a GOP stronghold, Gwinnett flipped blue in the 2016 presidential election, and Rich defeated her Democratic challenger by just 4.4% in 2020 after first winning the seat in 2018 by nearly 12%. Rich’s district has a growing Asian American population and three of the four neighboring districts in Gwinnett County are held by Democrats.

Does the redistricting body have a partisan balance?

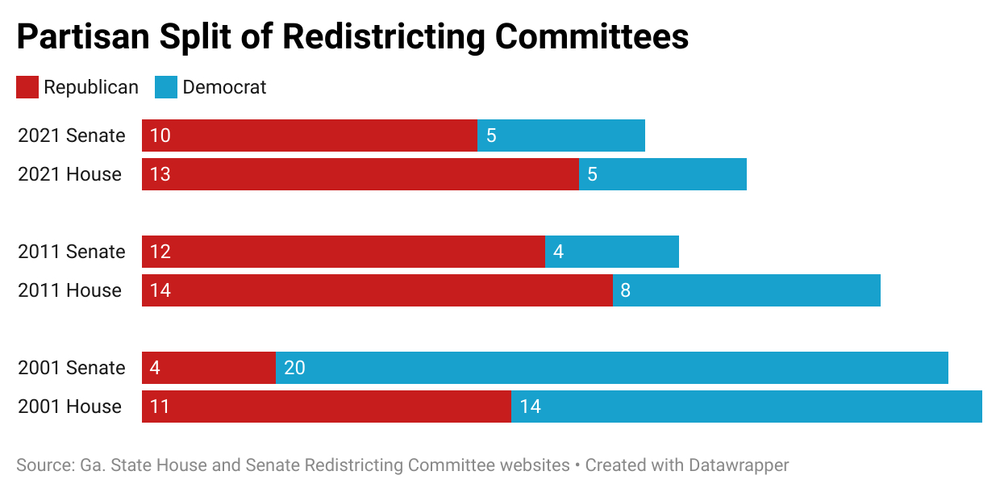

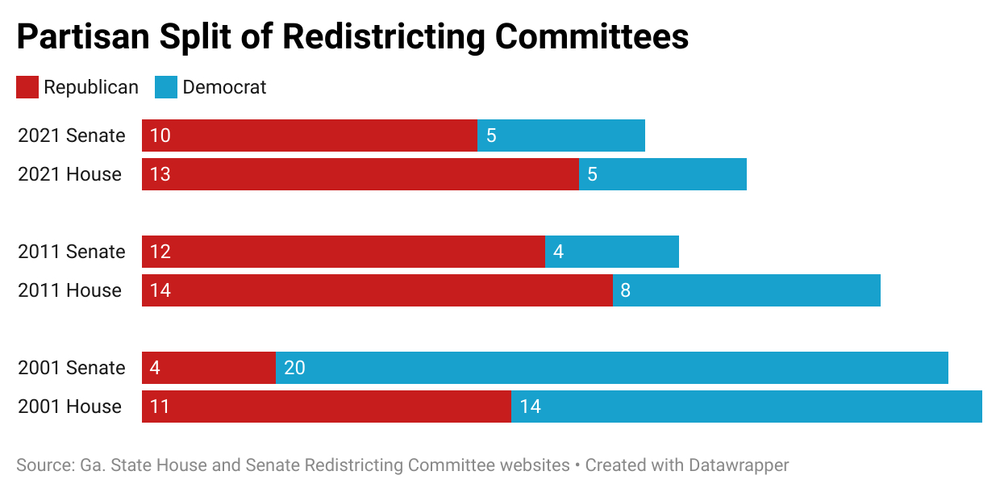

The partisan nature of the process is reflected in the makeup of the committees. This year's committees are dominated by Republicans. In the Senate, 10 of the committee's 15 members are Republicans. In the House, 13 of 18 are members of the GOP. A similarly lopsided partisan breakdown existed during the GOP-led process in 2011 and Democrat-led process in 2001.

Do the people who draw the lines reflect the state’s diversity?

While Georgia is estimated to be only 52% white and is more than 51% female, the redistricting committees are dominated by white men (House, Senate).

Is the redistricting body accountable to anyone?

In Georgia, the redistricting process is subject to very little accountability.

In theory, members of the redistricting committees are accountable to voters, who could vote them out of office. In practice, this is unlikely since the process allows the majority party to design districts that protect incumbents.

While the governor can veto the maps drawn by lawmakers, when the same party controls both the General Assembly and the governor’s office, as is currently the case, it would be unusual for that authority to be invoked.

For nearly half a century, to ensure compliance with the 1965 Voting Rights Act, Georgia and 15 other states with a history of voter discrimination were required to receive approval from the U.S. Justice Department before making any change that would affect voting, including changes to district maps.

The Supreme Court struck down that requirement in 2013, with a landmark 5-4 decision in the case of Shelby County v. Holder, ruling that it was excessive and no longer necessary. As a result, the burden of proof has shifted.

Instead of the state having to prove to the Justice Department that maps are not discriminatory, in the post-Shelby era, anyone seeking to challenge the maps has to prove in court that they are discriminatory.

“There really is no check and balance on that process whatsoever,” said Ken Lawler, board chairman of Fair Districts GA, a nonpartisan organization that advocates for maps being drawn without political bias. “And so, you know, clearly they can act in self-interest, pretty much without any issues.”

Does the redistricting body explain its criteria for drawing districts?

The committees have not yet announced what principles they will apply in drawing new maps. At recent town halls, Sen. John Kennedy (R-Macon), chair of the Senate Reapportionment and Redistricting Committee, has said the committees would adopt guidelines at their first public meeting once a special legislative session gets underway in the fall.

Kennedy told the Georgia News Lab that while the specifics will have to be worked out by the committee members, he believes many of the “core principles” used in 2011 (which were the same for the House and the Senate) will be included in this year’s guidelines.

The map-drawing principles adopted in 2011 stated that:

- Congressional districts should be drawn to include a population of “plus or minus one person from the ideal district size,” in line with the equal population requirement of the U.S. Constitution;

- State legislative districts should be drawn to achieve a population that “is substantially equal as practicable,” considering the committee’s other principles;

- The plans would comply with the Voting Rights Act, as well as the U.S. and Georgia constitutions;

- Districts would be “contiguous,” a requirement of the state Constitution, and

- There would be no multi-member legislative districts. (Congressional districts must be single-member by federal law.)

The principles also noted that the committees “should consider”:

- The boundaries of counties and precincts;

- Compactness, having the minimum distance between parts of a district;

- Communities of interest, groups of people with a common set of concerns based on factors such as ethnicity, race, economic interests or geography, and

- Making efforts to avoid “the unnecessary pairing of incumbents,” meaning races that would create contests between incumbents.

Despite that guidance, the maps Republicans drew in 2011 included 20 paired incumbents. The races featured six sets of Democrats facing off against one another and four sets of Republicans, according to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

In 2001, when Democrats controlled the process, the guidelines the committees adopted did not include any reference to limiting pairing. The maps they drew pitted 24 Republican senators against each other, the AJC reported. In the House, the Democrats paired 37 of 74 Republican candidates, as well as nine Democrats and an independent.

The guidelines are not legally binding on the committees. And in both 2001 and 2011, the committee members gave themselves leeway by including a provision stating, “The identifying of these criteria is not intended to limit the consideration of any other principles or factors that the Committee deems appropriate.”

The guidelines did not give any indication what those factors and principles might include.

Are state freedom of information laws or public meeting laws available to force disclosure?

In Georgia, the legislature is not subject to state open records or open meetings laws, limiting the public’s ability to monitor the redistricting process.

In 2001 and 2011, the guidelines adopted by the redistricting committees included provisions stating that all “formal meetings” of the full committees would be open to the public. The guidelines made no allowance for public access to other discussions about the work of the committees. And there were no stated limits on private discussions on private meetings about plans.

This year, Kennedy and Rich have already been holding closed door meetings with lawmakers to discuss their districts.

In 2011, the first time the full committees met, the sessions were held on the same day, at the same time, in different buildings at the state capitol. Public interest groups complained the arrangement limited citizens’ ability to monitor the process.

The Republican committee chairmen defended the arrangement, saying it allowed them to better coordinate plans.

"We felt like this was a good thing to do," Senate committee chair Mitch Seabaugh (R-Sharpsburg) told the AJC. "There will be ample time for individuals who want to go back and forth between the two."

For many years, Georgia’s Open Records Act contained a provision that allowed for public disclosure of services provided to legislative committees by three offices, including the Legislative and Congressional Reapportionment Office, which draws maps for the redistricting committees. It excluded disclosure of records of services provided to individual members of the legislature.

That section of the act was quietly removed in 2018, as part of a bill focused on the unrelated issue of protecting the personal information of certain foster parents.

In a letter to lawmakers in April, the coalition led by Fair Districts GA called on the General Assembly to waive what they called these “secrecy provisions” during redistricting deliberations.

Are the Census, demographic and political data used to draw district lines publicly available?

The redistricting committees have in the past disclosed very little about what information, other than Census records, they’ve used in drawing maps.

In addition to Census figures, all states use at least some data on race and political affiliation in order to ensure compliance with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color or membership in certain language groups.

Beyond that limited purpose, at least six states—including California, Montana and Utah—prohibit the use of partisan data in drawing district maps.

Asked by the Georgia News Lab whether all of the data used by the committees would be made public, including political data such as voter registration records, Kennedy did not directly address the question, saying only that he was waiting on the release of Census data that would be used along with public comments.

“We're going to take a very broad brush and try and get as much public input as we can,” Kennedy said.

Rich said she did not know whether political data would be made public.

“I have no idea,” she said. “It's my first time doing this. My knowledge is limited.”

The guidelines adopted by the committees in 2001 and 2011 called for public access to Census data used by the committees or the Legislative and Congressional Reapportionment Office, subject to “reasonable charges for search, retrieval, reproduction and other reasonable, related charges.” (In fact, Census data is available free of charge from the Census Bureau.)

In an apparent nod to the since-deleted section of the Open Records Act, the guidelines excluded public release of redistricting data prepared by the LCRO on behalf of individual legislators, unless the information had been publicly presented to committees.

Georgia’s use of political and racial data in drawing district maps became explicit in the course of a federal lawsuit alleging that plans to redraw several districts in 2015, constituted racial and political gerrymandering in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Voting Rights Act. In a deposition in the case, the state’s chief mapmaker, Gina Wright, the Executive Director of the LCRO, acknowledged using information about precincts’ political leanings and racial makeup in drafting district boundaries.

“Since my objective was to make these districts, if at all possible anyway, better for these incumbents to get reelected, then that political data was my primary objective to look at,” Wright said.

At least 18 states prohibit drawing maps that favor or disfavor an incumbent or candidate.

Wright said she also looked at race data “to make sure that I did not do significant harm” such as making a significant change in the percentage of African-Americans in a district.

Are draft maps made public?

The committees have not yet announced their plans for releasing maps.

The guidelines adopted in 2001 and 2011 stated that all plans submitted to the committees “will be made public in the same manner as other committee public records.” Elsewhere the guidelines said that all plans presented “at committee meetings” would be made available for public inspection.

The guidelines did not indicate when the plans would be made public.

In 2011, the public got its first glimpse of proposed legislative district maps on the Friday before the Monday start of the special session. Even individual lawmakers had only seen the plans for their own districts until then, according to the AJC.

The House and Senate redistricting committees approved the maps for their own chambers on Tuesday, the second day of the session. The full General Assembly approved the plans a week later, almost entirely along party lines.

Lawmakers unveiled maps of proposed congressional districts a week after the start of the special session. They approved the plans two days later.

Can the public submit redistricting plans?

Because the committees have not yet adopted guidelines, it is not known what the rules for submitting plans will be.

In both 2001 and 2011, the committees’ guidelines stated that redistricting plans could be submitted “only through the sponsorship of one or more Member(s) of the General Assembly.”

The guidelines laid out explicit criteria for the format in which the plans were to be submitted and the information that had to be included.

Redistricting commissions in New Mexico, Utah and Washington recently introduced new tools that allow members of the public to draft and submit district plans online.

No such avenue yet exists for Georgians.