Caption

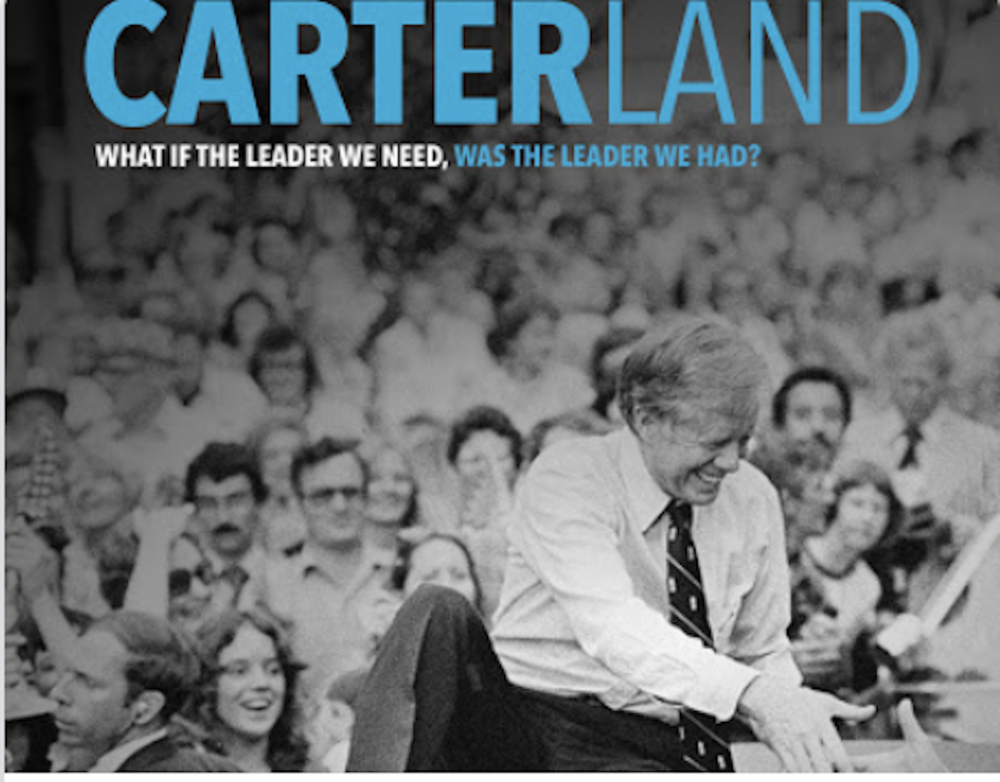

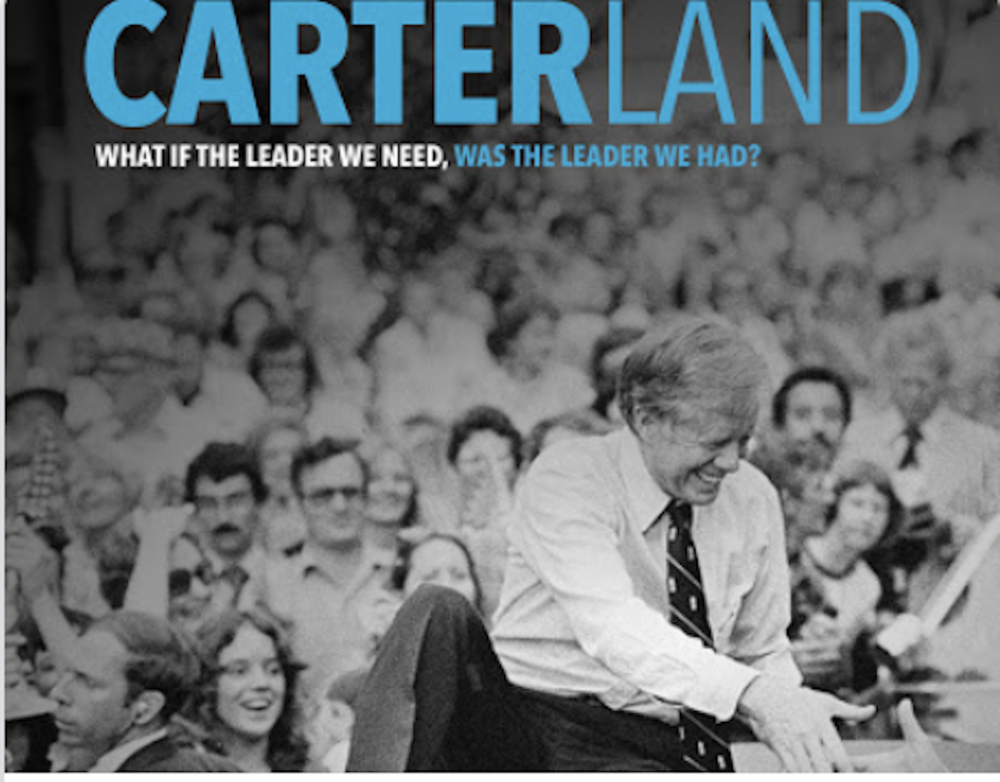

Former President Jimmy Carter riding atop a car in 1979 through Bardstown, KY., is shown in the trailer poster for the documentary film "Carterland," produced and directed by Jim and Will Pattiz.

|Updated: April 29, 2021 12:38 PM

Former President Jimmy Carter riding atop a car in 1979 through Bardstown, KY., is shown in the trailer poster for the documentary film "Carterland," produced and directed by Jim and Will Pattiz.

Jimmy Carter may be the only American president to have used the White House as a stepping stone. Turned out of office after one term, Carter went on to global esteem as a champion of public health, a geopolitical negotiator, and an advocate for democratic representation.

His legislative record as president tells another story. A number of recent books, articles and documentaries cast Carter’s legacy as the nation’s 39th president in a new light.

While praised for his determination to promote peace between Israel and Egypt through the Camp David Accords, Carter is less well known for diversifying the judiciary, establishing diplomatic relations with China, and for a slate of economic and energy environmental policies which have changed the way we live today.

On this episode of Georgia Today: Co-host Virginia Prescott speaks with Georgia-born brothers and filmmakers Will and Jim Pattiz, who revive the debate over Carter’s White House legacy in their new film Carterland. The documentary makes its world premiere at The Atlanta Film Festival on Saturday, May 1.

RELATED LINKS:

Virginia Prescott: This is Georgia Today; I’m Virginia Prescott. Jimmy Carter left the White House a one-term president. He was battered by foreign policy catastrophes, a domestic economy in shambles and rock-bottom approval ratings. In the 40 years since, the man from Plains, Georgia, has become a global humanitarian and Nobel Prize winner.

Walter Mondale: The story usually goes about President Carter: “Well, he's a nice guy and a good person, a great ex-president, but he's a failed president who was never really able to rise to the challenges of his time.” That's what you hear. That's the story we've been told. But it's all wrong.

Virginia Prescott: That was Walter Mondale, Carter's vice president, who died last week (on April 19). Among those telling a different story are Will and Jim Pattiz, the Georgia-born brothers and filmmakers behind the new documentary Carterland. The film is the latest to cast Carter's legacy in a different light, as a farsighted, even revolutionary president.

Virginia Prescott: Well hello, Pattiz brothers.

Will and Jim Pattiz: Hey Virginia, thanks for having us.

Virginia Prescott: Now, you both grew up in Georgia. What did you know growing up about Jimmy Carter?

Will Pattiz: So growing up in Georgia, we were kind of not told too much about President Carter. We kind of had this basic understanding that he was a phenomenal human being. Then, we had heard this phrase, "the greatest ex-president ever." But about his presidency, you don't hear too much. We didn't hear too much anyways. And what we did hear were not positive things about him. And so that was one of the things that really drove us to making this film was saying, you know, this is really a story that hasn't been told before. And as we got to researching it, we said, “Holy cow, there is so much here.”

Jim Pattiz: We're excited to kind of share the real story.

Virginia Prescott: Well, let's talk about that real story. He gets elected. This was in the wave of post-Watergate elections. He’s not a politician. He's been in the state senate here in Georgia and, of course, governor of Georgia. But sounds like there's a lot that he didn't really get about Washington.

Will Pattiz: One of the interesting themes of the film that we cover is this idea of an outsider. He comes in and one of the problems he immediately faces, is he brings in a total outside crew. And in Washington, folks are used to you kind of, quote unquote, playing ball. He doesn't do that. Even President Carter really didn't do a lot of the greasing of the hands. He didn't like this transactional politics — “I'm going to do this thing for you because you will do this thing for me.” He brings a very different attitude, which is, “I'm going to do this thing because it is right.” And that ruffled a lot of people's feathers.

Robert Strong: Carter was one of those people, when he said, “I'm going to do the right thing, not the political thing,” he was telling the truth. That's rare. That's hard for other people to imitate. And it cost him at the time. But as we look back on it, it looks more and more admirable.

Virginia Prescott: So what are some examples of Jimmy Carter doing the right thing, despite what sounds like a high political cost?

Jim Pattiz: This really becomes a theme in his presidency, and in our film. We spoke with his son, Chip Carter, when we were making the film, and he talks about how — and Jason Carter, his grandson, as well — they talk about how [former first lady] Rosalynn Carter was really the best politician in the family, hands down. And she advised him, you know, she was his closest adviser. One of the things was the Panama Canal. She said, you know, that really should wait till the second term.

Chip Carter: You know, my mother would be a lot more leery of taking on the controversial issues than my father because my mother was looking toward the next election. My father was looking toward the next day and what he could do to make our country better.

Jim Pattiz: But President Carter just felt like, if I can do it now, it needs to get done and that we're talking about negotiating a treaty to hand over the Panama Canal, you know, back to the Panamanians, which was a really politically fraught issue here at home. But in Panama, the situation on the ground was, it was looking like it was going to break out into full-scale war there if something wasn't done. And so Carter really takes on the politically unpopular issue of transferring what was then American property to Panama, returning it to the Panamanians. And obviously, it was a great decision. And Carter talks about, you know, when he gets this incredibly heavy lift done in Congress and he gets this thing signed, passes it by two votes in the Senate, and he says that, you know, this treaty demonstrates the kind of great power the United States wants to be: treating our neighbors with fairness and not force. Obviously, after President Carter, you see a lot of presidents who don't necessarily take that approach with their foreign policy. So that was, Carter paid a heavy price for the Panama Canal. I think he lost 20% on his approval ratings. And, of course, Ronald Reagan was out there building his political career off of taking the opposite view. So that was a big one for Carter.

Jimmy Carter: Although the Panama Canal treaty was a misunderstood move that our government made — it was not politically popular — I don't have any doubt that I lost a lot of political support on account of it. But it was right and I would rather be right in a case like that when I'm sure it's for the best interest of our country, even if it does cost me something politically.

Jonathan Alter: His faith, his belief in human rights and his environmentalism all contain a moral imperative. They all are connected to a deep sense of morality that suffuses his attitude toward life.

Virginia Prescott: What does that sense of moral leadership bring to his quality as a president? What does he get done?

Jim Pattiz: I think that the question of morality for Carter, that — that is central to who Carter is and it overrides everything else that — that he does. Douglas Brinkley, a historian, he talks about how one of the things with Carter is, is that he really has no greed and that can be a problem in American politics. That he was not going to compromise his morals on an issue that was — that was important. And we see that throughout his presidency, whether it's, you know, in the wake of the Love Canal disaster, he goes and enacts the Superfund bill, you know, Alaska lands. If Carter doesn't step in and use executive action and really lead on that issue, Alaska would be a very, very different-looking place today.

Jimmy Carter: I've seen firsthand some of the splendors of Alaska but many Americans have not. Now, whenever they or their children or their grandchildren choose to visit Alaska, they'll have the opportunity to see much of a splendid beauty undiminished and its majesty untarnished.

Virginia Prescott: OK, so through using this executive action — the Antiquities Act — he protects 150 million acres in Alaska and eventually doubles the size of the national parks. Where else do you see him as a visionary on the environment?

Will Pattiz: This first actual speech that he gives the American public is done in a totally different style than what you see with most politicians. You have to go back to President Franklin Roosevelt to get a very familiar reference point. And it is him sitting in front of the fireplace wearing this cardigan sweater. And he says, I want to talk to you tonight about energy and energy conservation, specifically. And you see this very calm-demeanored man who looks like he could be your dad or somebody who's talking to you in a very familiar sense. And he talks to the American public about this idea of energy conservation.

Jimmy Carter: I ask you to drive 15 miles a week fewer than you do now. At least once a week, take the bus, go by carpool, or if you work close enough to home, walk.

Will Pattiz: An interesting story that Vice President Mondale told us when we were interviewing him was about how Carter walked the walk, so he gave this speech on lowering thermostats. And so in the summer, he told us how in the even in the Cabinet room, he did the same thing that he told everybody in their homes to do. And he said, you'd come into the Cabinet room.

Walter Mondale: And it was 90 degrees and hot and muggy. You take off everything you dare take off without being arrested and try to make it through the day.

Will Pattiz: And if you can imagine the president of the United States, the vice president and his Cabinet having sweaty Cabinet meetings. And it's, you know, for Americans very used to taking — you know, we're used to not really saving. We turn on the lights, we leave the room. It's fine. Whatever. Americans, I think, are a little bit wasteful in our everyday actions. And what President Carter was saying is by now we're in a bit of an energy crisis and we need to save. So if you can turn out the lights, lower your thermostats, do what you can to conserve. And that was really only the beginning for him from that platform. He goes on to really try to tackle our energy problems for the future as well. He's the first president who put solar panels on the roof of the White House and does this in the 1970s, which is really just, when you think about it, it's crazy. He was pushing this idea of a new energy future, as Gov. Jay Inslee puts it in the film. And when you look back at it, you say to yourself, “My gosh, what happened?”

Jim Pattiz: Jason Carter has this great line. He talks about his grandfather was really the first millennial president. That really struck us because he's right. I mean, you look at the issues that Carter is out in front on in the 1970s and they're issues that we're only just now confronting today.

Will Pattiz: Jim’s talking about racial equality, social justice, climate change, energy, renewable energy, all of these things, you know, even ethics in government, all these things that are coming into the focus now, that he was doing in the ’70s.

Jimmy Carter: The only way to overcome unequal history is to promote and defend and enforce the equal opportunity for all disadvantaged Americans in this land. It's not enough to have a right to sit at a lunch counter if you can't afford to buy a meal and a ghetto looks the same even when you're sitting in the front end of a bus.

Virginia Prescott: So why didn't President Jimmy Carter get reelected? Stay with us for more Georgia Today. I'm Virginia Prescott.

[BREAK]

Virginia Prescott: It's Georgia Today; I'm Virginia Prescott. For years now, Jimmy Carter has largely been thought of as a failed president but a noble ex-president. Critics consider him weak on the Iran hostage crisis, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and not quite up to the task of taking on runaway inflation. His legislative record tells another story. The new film Carterland by Will and Jim Pattiz, presents a visionary president with farsighted policies on the environment, diversity, ethics, human rights and other issues we are still wrestling with today. But in the film, Princeton University historian Meg Jacobs says Carter struggled to ignite the passions of voters.

Meg Jacobs: A good leader is hard to define. A good leader, my first instinct’s to say the one who can turn out the votes because you really can't be a leader unless you're in office. And so you have to inspire people to want to support you and make them believe that you have better solutions than the other guy. And that was a challenge for Jimmy Carter.

Virginia Prescott: Well, you paint a picture of a thoughtful, highly intelligent, almost prescient president, why has Jimmy Carter gotten such a bad rap?

Will Pattiz: I think that's a — that's a really good question. You know, there are a lot of answers to that. I think one of the most obvious ones to us, at least, was when Carter loses reelection, and Ronald Reagan, you know, we have a pretty long succession there of Republican presidents. And Will and I feel like Carter's story was really being told by his successors who — who came from the opposite party. And, when Carter loses reelection in 1980, it's a clash of ideals. Carter wants to take the country in one direction and Reagan wants to take it in another direction. And Carter kind of outlines this in his “malaise” speech, if you will, which — he never used the word. We like to call it the “crisis of confidence” speech.

Jimmy Carter: There are two paths to choose. One is a path I've warned about tonight. The path that leads to fragmentation and self-interest. Down that road lies a mistaken idea of freedom; the right to grasp for ourselves some advantage over others. All the traditions of our past, all the lessons of our heritage, all the promises of our future point to another path. The path of common purpose and the restoration of American values.

Jim Pattiz: But he kind of outlines those two paths, and so I think when — when you had the other path gets chosen, they got to write President Carter's history.

ABC News tape: The latest ABC News Lewis Harris poll shows that Mr. Carter has now hit not merely a new but an all-time low in popular support. The president's return home to deal with the nation's troubles brings him face to face with his own problem — an unprecedented downturn of public opinion. According to our latest ABC News-Harris poll, the American people are giving him their lowest marks ever for the overall job he is doing. The rating 73% negative, 25% positive makes him the worst-regarded president in modern political history.

Virginia Prescott: Obviously, the wisdom of Jimmy Carter aside, people weren't willing to support him. Why couldn't Jimmy Carter get people to buy into his vision?

Will Pattiz: Jonathan Alter kind of tackles this in the film as well, he says President Carter is putting out all these incredible visionary things. And yet when he turned around, he realized that nobody was following him. And it's kind of a sad assessment of what was happening. But one of his flaws, potentially, is that he took on so much and he wasn't a great cheerleader for his own actions. And so now I think one of the results of the Carter presidency, a lesson, is that you do have to be your own cheerleader. You do need to go on TV regularly and say: “Look at this that I have done. I am being successful. See, look at this big policy thing that I achieved.” President Carter was really more about the results side of politics. He was a policy wonk and he really wanted to get things done. I think it is Phil Weiss, who is now the vice president at the Carter Center. In the film, he says that after the Panama Canal treaty is signed and this — this major legislative achievement that nobody thought could happen, you know, they celebrated in the West Wing of the White House for about five minutes and then they got right back to work because that's just kind of the guy that he was. And so, if people don't know all the amazing things that you're doing, then that's a real problem politically.

Virginia Prescott: One of the points that, I think it's Jonathan Alter — who wrote a terrific biography on Carter's years in the White House — he said, you know, Americans, they don't want to sacrifice.

Jonathan Alter: Carter was really the last American president who asked for sacrifice because that's — that's a political loser. People don't really want to sacrifice.

Virginia Prescott: So in some ways, this is the president, he's the eat-your-spinach president. You know? He's asking about big questions of meaning and the future. Was Jimmy Carter just too deep for America? Was it — was he too forward-thinking?

Jim Pattiz: It's a very good question. It calls to mind when Carter was president, you know, he was getting lampooned on Saturday Night Live for that very thing because Carter was an engineer. And he was very forward-looking, very deep-thinking, not only spiritually, but in tackling real problems. And Saturday Night Live, of course, famously does this caricature of him when he does the call-in show with Walter Cronkite and he has Americans calling in, and he has answers for all of their problems, including, you know, odd tax forms and things like that. He knows everything.

SNL Clip: Live from the White House, Ask President Carter. Mrs. Horbath, do you have a question for the president?

SNL Clip, Mrs. Horbath: Yes, sir. I'm an employee of the U.S. Postal Service in Kansas. Last year, they installed an automated letter-sorting system called the Marvex 3000 here in our branch. Yes, but the system doesn't work too good. Letters keep getting clogged in the first level sorting grid. Is there anything that can be done about this?

SNL Clip, Dan Akroyd as President Carter: Well, Mrs. Horbath, Vice President Mondale and myself were just talking about the Marvex 3000 this morning, as a matter of fact. I do have a suggestion. You know, the caliper post on the first-grade sliding armature? [Yes]. OK, there's a three-digit setting there where the post and the armature meet. When the system was installed, the angle of cross-line was put in a maximum setting, one. If you reset it at the three mark, like it says in assembly instructions, I think you'll solve any clogging problems in the machine.

SNL Clip, Mrs. Horbath: Thanks, Mr. President. By the way, I think you’re doing a great job.

Jim Pattiz: And he gets made fun of for that, but you wonder, should we have listened to this guy? Shouldn't we value somebody who has that kind of foresight, that kind of intelligence, and wants to ask more of us? And I think that's one of the real questions our documentary kind of challenges viewers to think about is, what do we really want out of a leader? Do we want a leader who's going to challenge us to be better versions of ourselves? Or do we want a leader who's going to ask nothing of us and is going to tell us that happy days are here? And that's — that's a real question for Americans as they go to the polls.

Virginia Prescott: My thanks to Will and Jim Pattiz, co-directors and producers of Carterland. The film premieres of the Atlanta Film Festival on Saturday, May 1. You can watch a trailer from Carterland and get more on Georgia Today at GPG.org. Georgia Today is a production of Georgia Public Broadcasting. You can subscribe to our show anywhere you get podcasts. And please do leave us a rating or review on Apple. Jess Mador is our producer. Our engineers and producers are Jesse Nighswonger and Jahi Whitehead. Steve Fennessy will be here with a new episode on Friday. I'm Virginia Prescott. Thanks for listening.