Caption

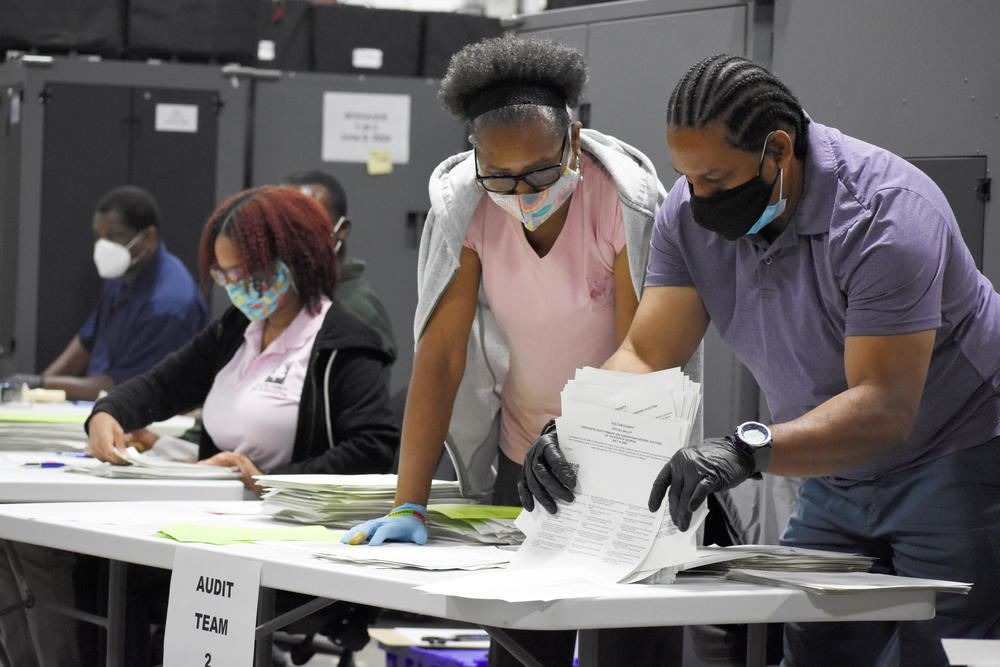

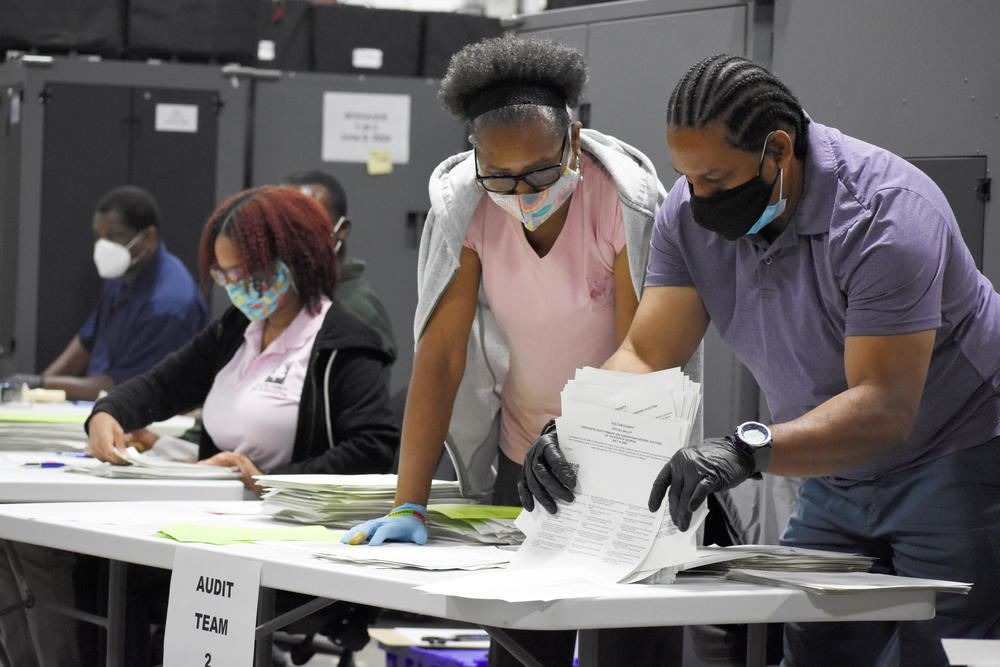

Fulton County election workers sort absentee ballots during a pilot audit after the June 9 primary.

Credit: Stephen Fowler | GPB News

|Updated: March 21, 2021 10:02 AM

Fulton County election workers sort absentee ballots during a pilot audit after the June 9 primary.

As lawmakers work on a massive voting bill that would make sweeping changes to how elections in Georgia are run, some local elections officials say the proposals would make their jobs harder and hurt voters.

GPB News and the Georgia News Lab contacted several county elections directors and reviewed testimony from several state House and Senate committee hearings to see how officials tasked with running elections say they would be affected by changes in upcoming elections.

The 2020 election cycle saw record-setting turnout, including 1.3 million absentee ballots in November, and unprecedented challenges because of the coronavirus pandemic. The presidential primary and general primary, delayed until June, saw longer lines, fewer voting locations and a shortage of poll workers. The presidential race was decided in Georgia by fewer than 12,000 votes and had 5 million ballots counted three separate times — including a full hand audit — before officials had to run a nationally watched January runoff that had both the state's U.S. Senate races on the ballot.

Many Republican lawmakers and officials spent the weeks after the general election pushing false claims of voter fraud and vowed to enact legislation that would change everything from absentee ballots, to vote counting, to the powers of the secretary of state. Some of the most controversial provisions would end no-excuse absentee voting, force large counties to cut back on early voting and stop automatic voter registration, three priorities that the secretary of state's office has touted while calling Georgia a leader in elections.

While the latest iterations of legislation appear to keep automatic voter registration, preserve no-excuse absentee voting and actually expand early voting access, dozens of provisions being considered would add financial and administrative burdens to the 159 local election supervisors across the state, Bibb County supervisor Jeanetta Watson said.

"We're all still so overwhelmed with trying to clean up after last year, how it's going to affect our budget, how we're supposed to staff," she said.

After dozens of counties received grant funding from the Center for Tech and Civic Life and the Schwarzenegger Institute, lawmakers are now proposing a ban on direct outside funding. But Watson said Bibb's grant funding was crucial to running the November and January elections.

"You're working with a budget that doesn't have enough funds in it for you to hire all the extra people that you need," she said. "We were able to take advantage of that grant last year and extend the funds for purchasing items that we so direly need in our offices. I think that would surely negatively impact elections offices if we were not able to receive those funds."

Watson added that without statewide elections in 2021, any changes to state law would not really be felt until the 2022 cycle, which will feature several hot contests, including the races for governor and U.S. Senate.

Another big change introduced in the 2020 election cycle was 24/7 monitored drop boxes, implemented as an emergency rule to give voters another option to return absentee ballots safely in the pandemic. Some Republican lawmakers have expressed skepticism about the safety and security of drop boxes, and some bills in the legislature would put a limit on how many a county could have and require them to be placed inside early voting sites. Instead of being accessible 24 hours a day, voters could only use them when in-person early voting takes place.

Tonnie Adams, the election supervisor for Heard County and legislative committee chairman for the Georgia Association of Voter Registration and Elections Officials, said the limitation on drop boxes would "render them useless."

"Not allowing the boxes to be open after hours forces voters that cannot drop their ballot off in the ballot box to put them in the post office, and, as we all know, the post office process was also a problem," he said in a committee hearing Thursday.

As an example, Adams said three absentee ballots sent in the day before a special election on Tuesday arrived late through the mail. Heard County does not have a drop box, but Adams said he supports making them available 24/7 instead of just during early voting hours.

Watson, the Bibb supervisor, echoed Adams' concerns.

"Any time you take something away that is supposed to maximize voting, and then you peel it back, it's gonna have a negative impact," she said. "I believe last year opened up a lot of doors for making sure any avenue a voter could take to make sure that their ballot was counted, the state implemented it, and it helped tremendously."

One of the biggest likely changes to Georgia election law would mostly end the process of signature matching, used to verify the identity of those who request and return absentee ballots. Lawmakers want Georgians to instead use their driver's license or state ID number in most cases, in reaction to baseless allegations of widespread fraud with the sharp increase in absentee ballots.

However, some elections officials say that matching voters' signatures is more secure than using an ID number and less susceptible to fraud or identity theft concerns.

But Randy Morrow, the Baldwin County registrar, said it could be a positive change.

"I don't see where it's been a big issue, because we look at signatures, but we're not handwriting experts," he said. "So we'd really depend on that other information as far as the date of birth, driver's license number and so on."

There is some concern among county officials that a new proposal to allow lawmakers or the State Election Board to take over low-performing elections boards and offices could be too much overreach into local control of elections.

"Personally, I think it's up to the county to make a decision on that," Morrow said. "It's kind of like the federal government wanting to control the states and how they vote. In turn, the counties have a better view of what they need than the state."

Another focus of lawmakers is on the vote-counting process after polls closed. Several sections of bills still floating around would require elections staff to count all ballots without stopping, wait to post election results until they could share the total number of votes cast and provide daily updates pre- and post-election about the number of ballots accepted, rejected and outstanding.

Joseph Kirk, the Bartow County elections director, said the way some of the language is worded concerns him because of potential emergencies that might delay counting, and he wants to remind the public that tabulation is never done on election night.

"I think every county out there has the goal of reporting results as quickly as possible," he said. "We don't want to be here late. We don't want to be counting ballots for days and days and days."

Kirk also said a push to remove the secretary of state as the chair of the State Election Board could create competing authorities on election rules and guidance, confusing counties and voters alike.

"What happens when the chairman of the State Election Board or the board as a whole and the secretary of state don't agree?" he asked. "It puts the counties right in the middle of that decision-making process."

Not every tweak to election law has been met with opposition by those tasked with overseeing our votes. Multiple officials have testified in support of language that would allow flexibility with voting machine allocation for lower-turnout races, an earlier deadline to request absentee ballots (though some have suggested the cutoff be eight days before the election instead of 11) and allowing an earlier start time to begin processing absentee ballots.

While Georgia is not likely to see more than a million people vote absentee in the future, many elections officials who responded to requests for comment support efforts to limit duplicate absentee applications sent out to voters from third-party groups that lead to confusion.

In the House, the omnibus voting bill to watch is SB 202 and the Senate is discussing HB 531.