Caption

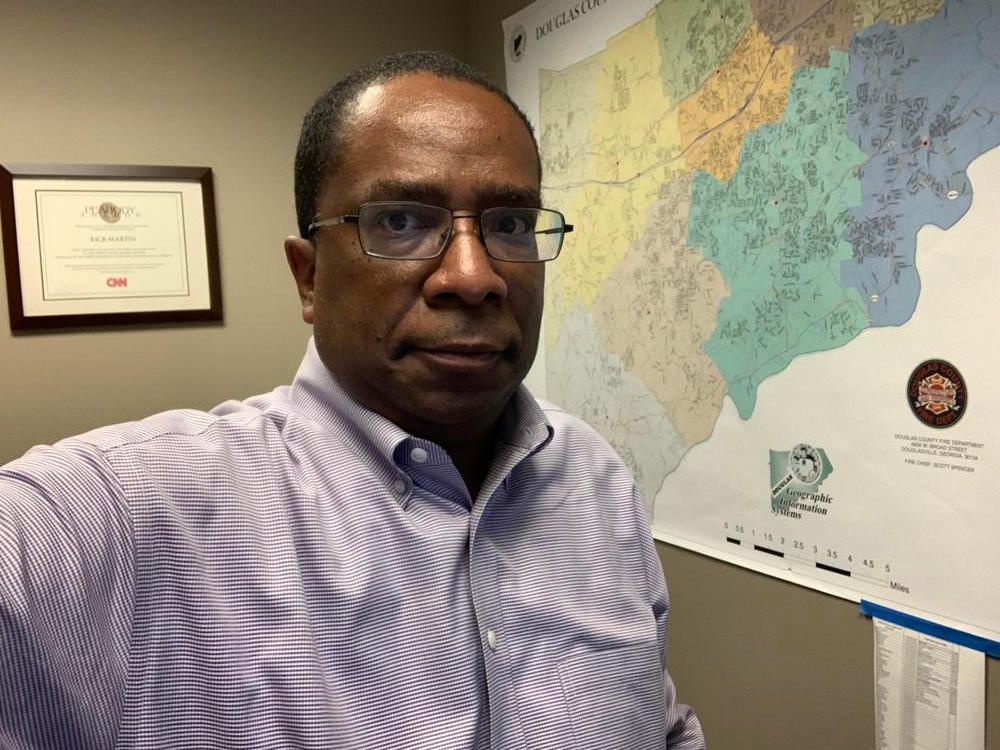

Rick Martin serves as communications director for Douglas County. He spent 17 days hospitalized with COVID-19, including five days on a ventilator.

Credit: Courtesy of Rick Martin

Rick Martin talks with GPB's Wayne Drash about surviving COVID-19

Rick Martin serves as communications director for Douglas County. He spent 17 days hospitalized with COVID-19, including five days on a ventilator.

Rick Martin lay in his hospital bed ravaged by COVID-19. His lungs could no longer breathe on their own. He lost much of his ability to move his arms and legs.

With a ventilator keeping him alive, his mind drifted, and a vision appeared.

He was attending a funeral at a church and looked around. He saw his two teenage daughters, Natalie and Madeleine, dressed in black. Then, his eyes spotted his father-in-law — who had died seven years before.

Seeing a deceased relative alive, Martin said, was “an experience I was not prepared for.”

A fear washed over him. He had not hugged his daughters or kissed his wife for weeks.

Was this how it was going to end?

“I was extremely frightened,” said Martin, 51. “I literally said, ‘You know, I’m not ready to go.’”

More than 720,000 Georgians have fallen ill from COVID-19; about 12,000 have lost their lives to the disease.

RELATED: Find Out Where In Georgia To Get A Vaccine

Around the state, almost every one of Georgia’s 10.6 million residents have been affected by the pandemic, from school closings to restrictions on our freedoms to the loss of jobs.

Rick Martin stands with his family. From left to right are his 15-year-old daughter Natalie, wife Adrienne and 13-year-old daughter Madeleine.

Many have lost friends and loved ones.

Others are like Martin: People who were on the brink of death, but somehow cheated it.

Many survivors don’t like to talk about their ordeal — it’s almost like a modern-day “scarlet letter” with the potential for public shaming if you discuss your experience. We’ve all seen the posts on Facebook and Nextdoor: Did you hear so-and-so got it?

Martin, a resident of Lithia Springs, is that rare survivor. He wants to tell his story to save lives. To tell anyone who will listen that being intubated and spending five days on a ventilator is not something you want to experience.

Folks need to stop all the bickering, the divisiveness — and enjoy life, he said. To tell those closest to you that you love them.

“I don’t leave a conversation at all with my wife without saying 'I love you,'” Martin said. “Man, I think I’ll be saying 'I love you' to strangers.”

/

Rick Martin on telling strangers he loves them

It was two days before Christmas when Martin’s fever grew concerning. His body ached all over. He stared at the thermometer twice: 101.9 degrees.

Adrienne, his wife of 16 years, said, “Let’s go!”

RELATED: Kemp Says Georgia Needs More COVID-19 Vaccine

Almost exactly one year earlier, Martin had become gravely ill with the flu and pneumonia. He spent nine days in the hospital then, including five days in the intensive care unit.

That was then. This was now.

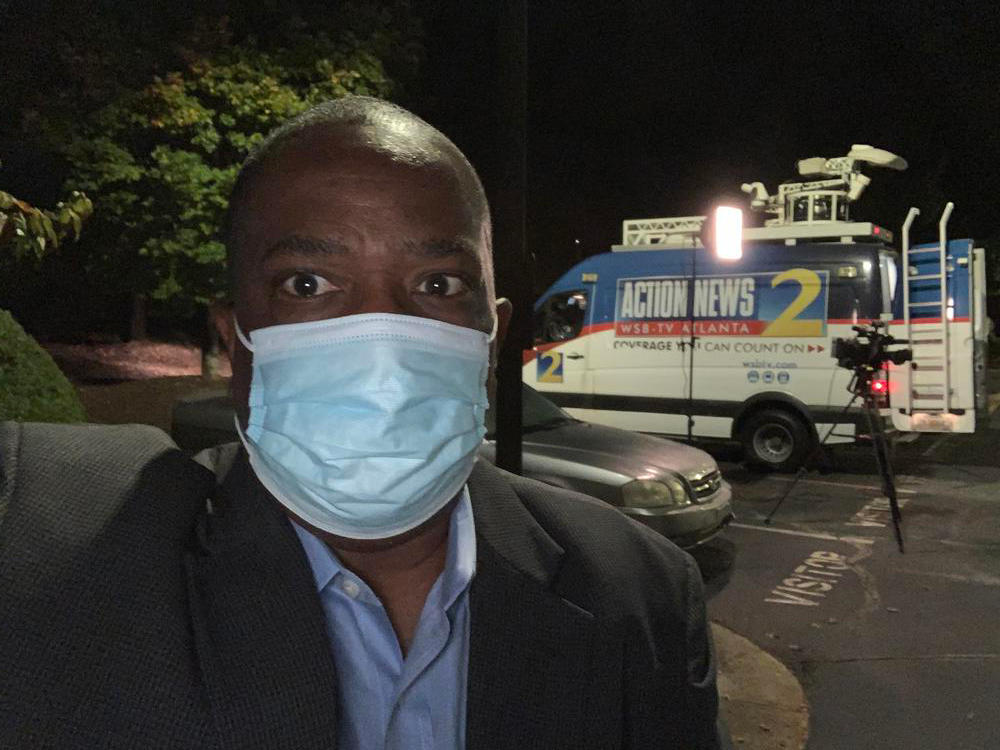

As communications director of Douglas County, Rick Martin often meets with members of the news media when news happens. Here, he practices COVID-19 protocols on the scene by wearing a mask and social distancing.

They weren’t going to risk anything. Martin knew how devastating COVID-19 could be. As director of communications and community relations for the Douglas County Board of Commissioners, he'd helped oversee communications on how to be safe against COVID-19: Wear masks, wash your hands and stay socially distanced.

The chief spokesman for Dr. Romona Jackson Jones, the chair of the board of commissioners, Martin hosted virtual town halls on how Douglas County was responding to COVID-19. He also held weekly virtual interviews with Dr. Janet Memark, the public health director for Cobb and Douglas counties, to provide the public with updates on how the region was faring with the coronavirus.

As a Black man, he also was well aware of how the disease has disproportionately affected people of color.

With his fever spiking, his wife rushed him to Wellstar Douglas Hospital in Douglasville, about 30 miles west of Atlanta.

His condition rapidly deteriorated.

“I experienced fear like I never imagined before,” Martin recalled.

On Christmas, doctors told him he needed to go on a ventilator.

“I vaguely remember them talking about a ventilator,” he said, “and I remember coming over with this sense of fear that if I’m put on the ventilator, I wouldn’t come off — that death would be that near.”

Martin doesn’t remember it, but he told the doctors: No.

“As a patient, I was heavily medicated and afraid that if I went on the ventilator, I wouldn’t come out alive,” Martin explained.

Doctors relayed the news to his wife. Scared for the love of her life, Adrienne was determined to change his mind. But by Dec. 27, he was still refusing the treatment, even as his health declined.

“If he does not go on the ventilator,” the doctor told Adrienne, “he will likely not survive the night.”

Martin's wife worked feverishly behind the scenes to do whatever it took. She called one of his best friends, an ER doctor in another state. He stepped her through the process of healing and recovery of a ventilator and told her to follow the doctors’ recommendations — that it was his best chance of surviving.

Known to deliver the invocations at Douglas County Board of Commissioners legislative meetings, Martin was now surrounded by prayer circles from all over the county — and the world. His family received messages of prayer from as away as Canada, countries in Europe and his parents' homeland of Trinidad and Tobago.

Every day, at 2 a.m., while Martin was on the ventilator, when his loneliness and isolation was at its greatest, his wife would call. A nurse would hold the phone to his ear. Adrienne would read Scripture and recite prayers:

O God

My dear one lays upon the bed in such need and I feel so helpless. I never thought it would actually come to me and my loved one. I need you more today than ever before. Send your healing touch our way. Heal my precious one, and my wounded spirit. Guard me from fear and doubts, lift my spirit that has sunk so low. I believe you are near, hear me O God.

Martin could not respond because of the tube down his throat, but he heard every word.

“The power of prayer is a mighty thing,” Martin said, “but you never know how mighty it is until your life depends on it.”

He doesn’t remember much beyond that and the vision of his father-in-law at the funeral. In addition to the ventilator, his treatment included the antiviral drug remdesivir, oxygen and a transfusion of convalescent plasma.

He came off the ventilator after five days, on Jan. 1 — the start of a new year and new lease on life. He made one request to the nurse.

“I want to call my wife,” he said, “to tell her, 'I love you.'”

Recovery after such an ordeal is slow. Martin was released from the hospital after 17 days, on Jan. 8, and transported via ambulance to the Riverdale Center for Nursing and Healing.

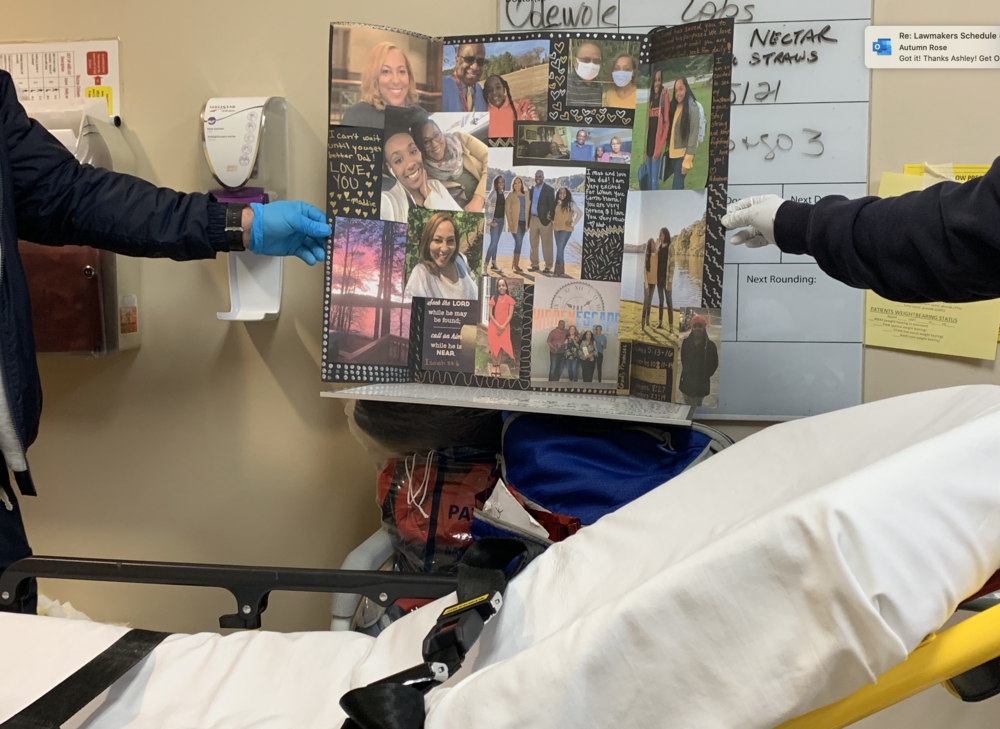

Nurses presented this family card to Rick Martin before he was released on Jan. 8. He left the hospital on the stretcher in the foreground and taken via ambulance to a rehabilitation center.

He had to learn how to drink again without choking. He was taught how to eat ice chips, then food. He underwent speech therapy to relearn how to talk. His muscles that relied on the ventilator needed strengthening, too.

“These are experiences that I never imagined I would be encountering: Having to learn how to walk with a walker and gain strength in my legs,” he said, “when, just a month before, you're walking, you're exercising or you're running. And then you're struck with the deadly virus.”

His rehabilitation consists of five days of one-hour exercises that include walking, sitting-standing repetitions and core body strengthening.

While in rehab, Martin’s family visited his room one Saturday by standing outside the window, part of the safety precaution so they would not be exposed to coronavirus.

Martin noticed a nondescript black minivan with tinted windows pull up outside behind them. Two staffers dressed head-to-toe in protective gear exited the van, pulled out a stretcher and entered the same wing where he was staying.

Before he began working in communications, Martin had spent 30 years in broadcast journalism, including 12 years at CNN. Perhaps it was the journalist in him, but he captured the moment of the staffers returning with a body on the stretcher and loading it into the van.

“I took video only to remind myself how fragile life is and how close I could have been on that same stretcher, wrapped in a sheet and taken away with no family, no friends,” he said.

Martin feels like more than a survivor. It's as if he's gone through an awakening. He and his 78-year-old father have always been close but, men being men, he said, they never told each other how much they loved one another.

Waking up alive has changed that.

“I want to encourage anybody who's listening out there,” he said, “don't wait until a near tragedy comes knocking on your door.”

Last Thursday, Martin walked out of the rehab center on his own, slowly and gingerly, to the surprise and delight of his wife and two daughters.

Once home, he was overcome with emotions. He grabbed his wife and held on tight for minutes. Their 15-year-old daughter joined in, too.

It is a moment, he said, he will always cherish.

He had one overwhelming thought: “God is not done with me yet.”

Martin plans to take advantage.