Caption

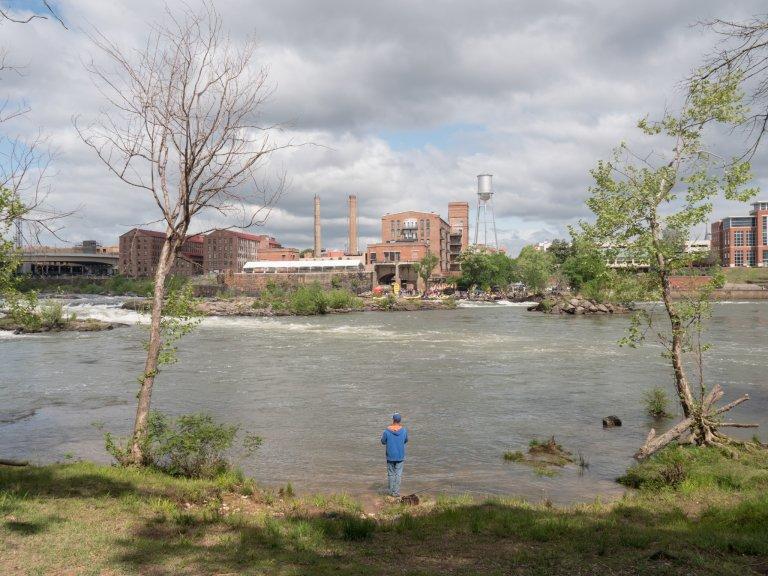

The segment of the Chattahoochee River that runs through Columbus is a popular spot for whitewater rafting and fishing. The Columbus Water Works is challenging new state requirements meant to protect water quality.

Credit: Henry Jacobs/Chattahoochee Riverkeeper