Caption

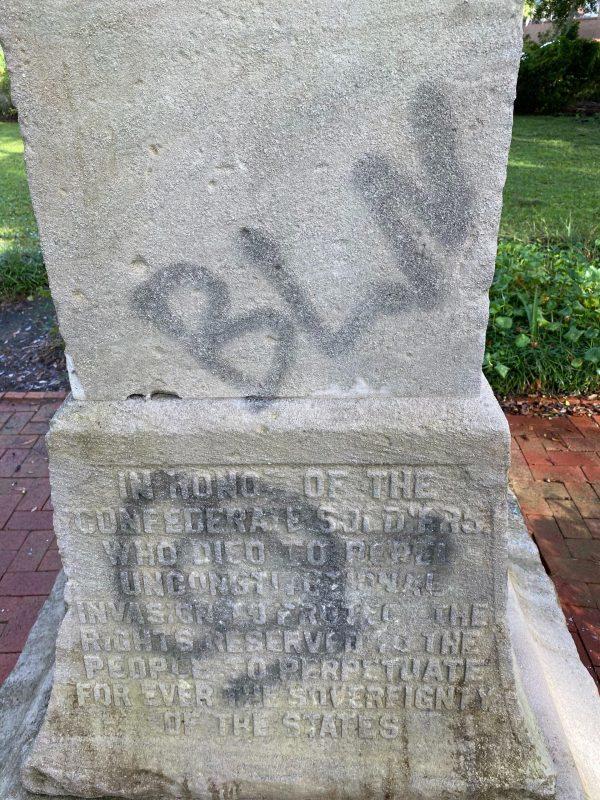

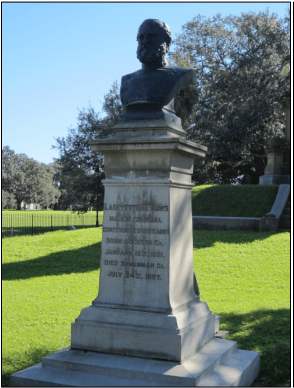

The fate of the monument has become a source of bitter debate pitting those who believe it represents the city’s racist past against those who see it as a tribute to their ancestors’ struggle to preserve a way of life.

Credit: Donnell Suggs/The Current