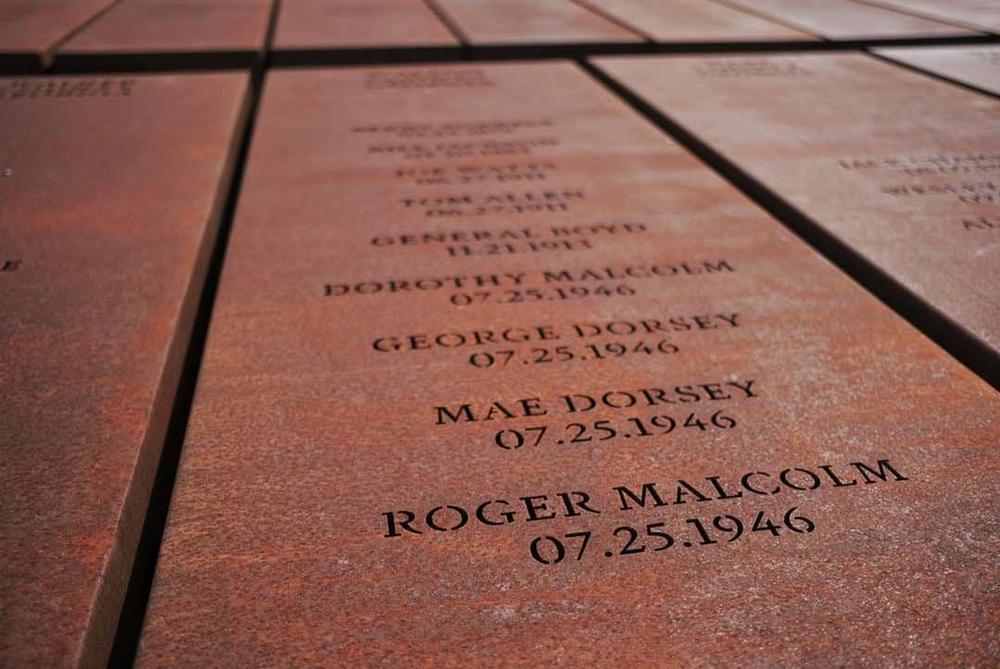

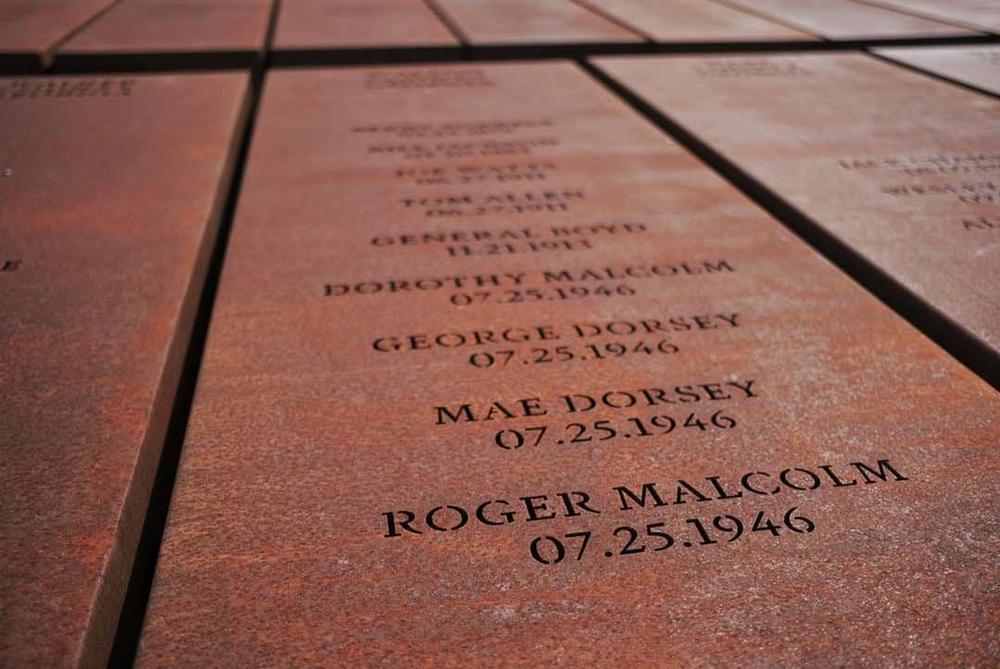

Caption

The names of the four victims of the Moore's Ford Bridge lynching are enscribed at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

Credit: Grant Blankenship/GPB

The names of the four victims of the Moore's Ford Bridge lynching are enscribed at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

The U.S. Supreme Court has said it will not hear arguments about unsealing grand jury documents more than 70 years old tied to a notorious Georgia lynching at Moore’s Ford Bridge in Walton County.

Two Black couples, George and Mae Murray Dorsey and Dorothy and Roger Malcom, were killed by a white mob at the bridge in 1946. While an FBI investigation at the behest of President Harry Truman ensued, and evidence was presented to a grand jury, no murder charges were ever brought.

Later, historians, first the late Anthony Pitch and now writer Laura Wexler, sought to make the grand jury records public.

In March, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals elected to keep the documents sealed. That ruling followed another by a smaller of body of judges in the same court which had said it would be proper to unseal the documents for the sake of history. Those conflicting rulings are what attorney Joe Bell asked the U.S. Supreme Court to resolve.

The court declined.

In so doing, the Supreme Court let stand the 8-4 opinion issued March 30 by the entire body of judges in the 11th Circuit that said it would be improper to release the grand jury documents in the Moore’s Ford Lynching case. The court said to do so would endanger the secrecy of every grand jury proceeding from that point on.

"The Supreme Court has long recognized that the proper functioning of our grand jury system depends upon the secrecy of grand jury proceedings,” the court ruled.

Those who study the Moore’s Ford lynching disagree over whether it was in revenge for the stabbing of a white man by victim Roger Malcom or was an example of voter suppression in the first year Black people could vote in the state’s Democratic primary. Both assertions are considered during the annual reenactment of the crimes in the town of Monroe.

Historian and author Anthony Pitch searched for years for the grand jury documents, which had disappeared from federal records before he somehow found them in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. He then spent the years up until his death in 2019 petitioning the courts for permission to read and share what he had found.

When Pitch died, his attorney, Joe Bell, pulled in Wexler, another historian and Moore’s Ford expert, as the party who would allow the case to continue. Wexler said there are still a maddening number of unknowns about Moore’s Ford with the grand jury documents still locked away.

"I mean, we don't know to what degree the U.S. attorney was really assertive and adamant and effective in presenting the case,” Wexler said. “We don't know to what degree people felt compelled or safe enough to tell the truth in front of the grand jury. We don't know what pressure the grand jury members felt from each other or from the judge to to vote a certain way.

"So there's a lot of stuff we don't know because it's like a locked box.”

Wexler said the inaction from the Supreme Court leaves two options for the release of the grand jury records. One: The Congress could change the section of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure relating to grand jury testimony secrecy, and two: the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Cold Case Initiative could take up Moore’s Ford again. The task force most recently mentioned Moore’s Ford in its 2018 report to Congress.

Meanwhile, those who had hoped the Supreme Court would finally let the world see what case there was to be made in 1946 at Moore's Ford will still be left hoping.