Caption

A group of University of Georgia freshmen play basketball behind the high rise dormitories on Baxter Street a few days before the start of the fall 2020 term.

Credit: Grant Blankenship/GPB

|Updated: September 11, 2020 4:06 PM

A group of University of Georgia freshmen play basketball behind the high rise dormitories on Baxter Street a few days before the start of the fall 2020 term.

Back in the late Spring, there were coronavirus trends in Georgia that Grace Bagwell Adams could clearly see.

Number One: The state did not have enough contact tracers for the coming spread of the virus. Contact tracers are like social workers and detectives. They find people who may have had contact with a sick person and help those people isolate themselves until they are sure they can’t spread the disease.

Number Two?

“We had a demand among our graduate and undergraduate students to really teach that skillset,” Bagwell Adams said.

Bagwell Adams knew that because she is an assistant dean in the college of Public Health at the University of Georgia.

“And then the third thing, it was clear at that juncture in early summer that the University System of Georgia was planning for a full in-person return,” she said.

Face-to-face instruction is the norm at Georgia’s state colleges and universities. And coronavirus cases are spiking in many of Georgia’s largest college towns, so much so that in the last White House Coronavirus Task Force advice to Georgia, the task force said college towns threaten to undo much of the work the state has done in fighting the virus.

And yet, there are some, like Bagwell Adams, who wonder how things might have been different on campus.

Given what she knew back in the spring, Bagwell Adams asked for, and got permission to teach, a summer class in contact tracing.

“Class actually filled up in less than a week,” she said. “My dean has been on the medical oversight task force. She's in the leadership and administration meetings constantly about COVID. And so she made it clear to UGA’s senior administration that this class is being taught, that we as a college had the capability and the willingness to train tracers.”

The administration was also told the cohort of 28 newly trained tracers would stand ready to help the University of Georgia meet its goal of traditional face to face instruction in the fall.

But today the number of people in the UGA contact tracing corps is zero.

“There is currently no in-house contact tracing occurring at the university of Georgia,” Bagwell Adams said.

In the meantime, UGA has racked up close to 2,600 COVID-19 cases, over half of that in the last week alone. The university blames off-campus activities like parties and going to bars for the spread, which Bagwell Adams says they might be able to prove, if they had the contact tracing to back it up. As it stands she says they don’t have the data. Neither UGA nor the USG has provided any proof of the assertion.

And of course what happens on campus affects the town.

The local school system wanted kids to start the year with what UGA students still have: face to face instruction. But, the virus case rate in surrounding Clarke County is going through the roof, too. It’s six times what Clarke County Schools considered safe, so grade school students are online.

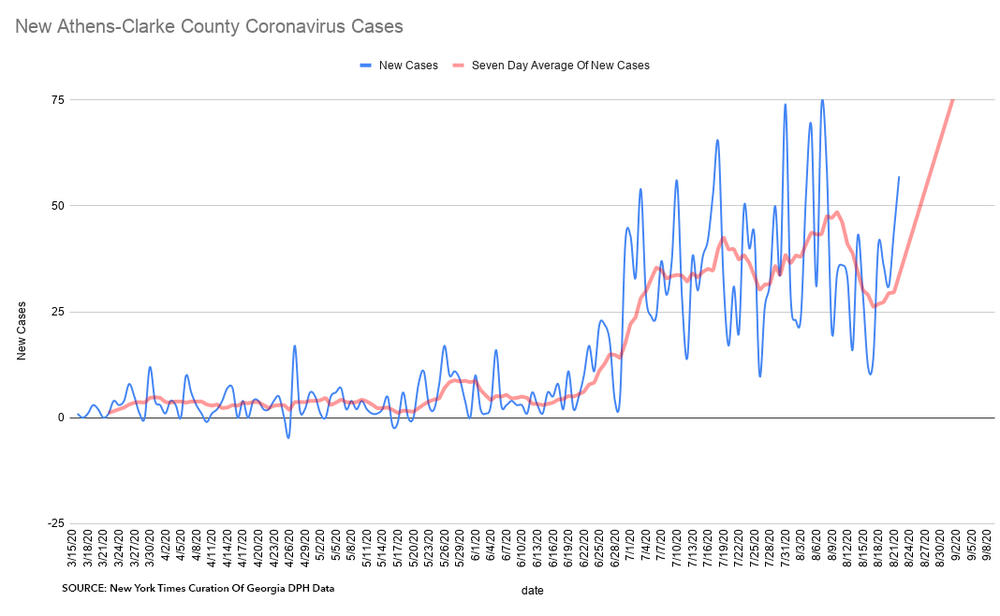

Athens-Clarke County coronaviruses reported daily. UGA students returned to the fall semester on August 24.

To begin correcting course, the White House Coronavirus Task Force says in its latest report on Georgia that the state’s colleges and universities should do what Bagwell Adams knew would be necessary back in the spring, and which it turns out the local public schools are already doing: manage your own in house contact tracing.

The UGA administration says that can't happen.

“Consistently, the message that has come from the administration from the University of Georgia, that continues to come from them, is that it is the sole responsibility of the Department of Public Health to conduct contact tracing. That it is not up to the University of Georgia,” Bagwell Adams said.

That is what UGA is saying, but DPH contact tracers were already strained before college students were back in class.

So now after having trained a contact tracing corps for the state’s flagship school, Bagwell Adams is left scratching her head as to why UGA didn’t employ the contact tracers it trained.

“I don't know what the forces are,” she said. “It's like, I know we're in an election year, I know that for some reason the pandemic has been politicized, but we're all working towards the same goal here.”

“We're all on the same team and we want to beat COVID-19.”

Some of Bagwell Adams’s students are out there, working toward that goal as contact tracers, some even with Georgia DPH. But as she watches the case count grow on campus, Bagwell Adams wishes things in Athens could be different.

“I wish that...” she stops, trails off, laughs, perhaps a little ruefully, then starts again.

“I would hope that we would collaborate and really ramp up and have our own in-person team,” she said. “And that just hasn't happened yet.”

Bagwell Adams said she plans on teaching the contact tracing course again in the summer of 2021.