Section Branding

Header Content

From Desert Battlefields To Coral Reefs, Private Satellites Revolutionize The View

Primary Content

As the U.S. military and its allies attacked the last Islamic State holdouts last year, it wasn't clear how many civilians were still in the besieged desert town of Baghouz, Syria.

So Human Rights Watch asked a private satellite company, Planet, for its regular daily photos and also made a special request for video.

"That live video actually was instrumental in convincing us that there were thousands of civilians trapped in this pocket," said Josh Lyons of Human Rights Watch. "Therefore, the coalition forces absolutely had an obligation to stop and to avoid bombardment of that pocket at that time."

Which they did until the civilians fled.

Lyons, who's based in Geneva, has a job title you wouldn't expect at a human rights group: director of geospatial analysis. He says satellite imagery is increasingly a crucial component of human rights investigations, bolstering traditional eyewitness accounts, especially in areas where it's too dangerous to send researchers.

"Then we have this magical sort of fusion of data between open-source, eyewitness testimony and data from space. And that becomes essentially a new gold standard for investigations," he said.

'A string of pearls'

Satellite photos used to be restricted to the U.S. government and a handful of other nations. Now such imagery is available to everyone, creating a new world of possibilities for human rights groups, environmentalists and researchers who monitor nuclear programs.

They get those images from a handful of private, commercial satellite companies, like Planet and Maxar.

For the past three years, Planet has done something unprecedented. Its 150 satellites photograph the entire land mass of the Earth every day — more than 1 million images every 24 hours. Pick any place on Earth — from your house to the peak of Mount Everest — and Planet is taking a photograph of it today.

"If you could visualize a string of pearls going around the poles, looking down and capturing imagery of the earth underneath it every single day," said Rich Leshner, who runs Planet's Washington office.

Scroll through Planet's photo gallery and you get a bird's eye view of the state of the world: idle cruise ships clustered off CocoCay in the Bahamas, deserted streets around normally bustling sites like the Colosseum in Rome, and the smoke from the relentless fires set by farmers clearing land in the Amazon rainforest.

U.S. government satellites are the size of a bus. Planet's satellites are the size of a loaf of bread. Planet is in business to make money, and its clients include the U.S. military and big corporations. But it also works with lots of nonprofits and other groups it never anticipated, like local governments that monitor how much legal marijuana is being grown in their communities.

"I am often surprised what people can think of when they are looking at something every single day," Leshner said.

Monitoring nuclear programs

When Melissa Hanham got out of graduate school about 15 years ago, she wanted to study clandestine nuclear programs.

"I wanted to know what was happening in North Korea," she said. "I couldn't go there. It's not the kind of place that would let some strange lady walk around and learn things."

Lucky for her, Google Earth was just getting off the ground.

"I didn't really know what I was doing yet. So I was sort of like, 'Well, where would I launch a missile from?' " she recalled. "So I searched around the town until I was sure I found the place. That was a really critical moment because it meant that me, Melissa Hanham, regular lady, could figure out where North Korea launched missiles."

Hanham is now at the Open Nuclear Network in Vienna. She's still tracking nuclear programs with open-source material — and it keeps getting more sophisticated.

"I think about the pattern of life at a place," she said. "Is there a helicopter that's arriving on the helipad? Because important people don't necessarily travel by bus."

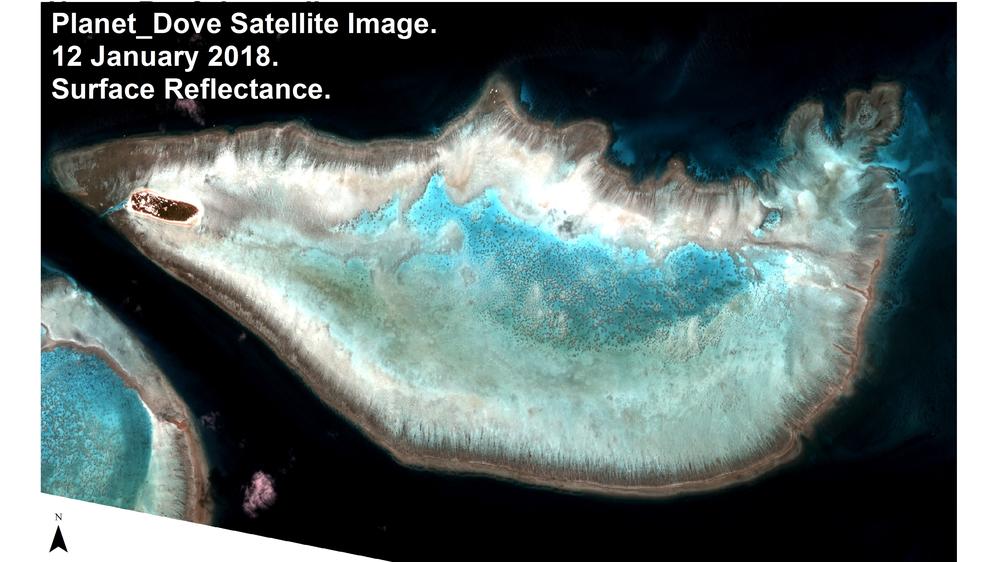

Charting coral reefs

In Seattle, Bill Hilf is the CEO of Vulcan, a company started by Paul Allen, the co-founder of Microsoft, who died in 2018.

"One of the challenges a Paul Allen gave us a few years ago was go and map all of the world's coral reefs," said Hilf.

At that point, the process was often low-tech.

"We have coral scientists at Vulcan who tell me stories about being underwater with an underwater clipboard to write down the dimensions of a reef. That doesn't scale. To really do it effectively, we needed the ability to use satellite data," he said.

The project, called the Allen Coral Atlas, now gets satellite images from Planet and works with National Geographic, governments, universities and local communities, from Australia to Madagascar, to assess tropical, shallow-water reefs.

These reefs are in trouble worldwide. The project aims to better protect them by taking steps like rerouting shipping lanes or working with coastal villages to prevent overfishing.

The satellite data provide a detailed look at tropical reefs to a depth of about 30 feet; deep-water reefs can't be seen from space.

"Our goal is by summer of 2021 to have 100% of [shallow-water] coral reefs mapped in the atlas," said Hilf.

From these reefs to the desert battlefields of Syria, these eyes in the sky are changing the way we see the world.

Greg Myre is an NPR national security correspondent. Follow him @gregmyre1.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.