Section Branding

Header Content

Georgia’s Predictably Problematic Primary Becomes A Reality

Primary Content

Georgia’s Republican secretary of state warned of long lines and problems with voting machines ahead of Tuesday’s primary, and as it came true in polling places across the state, blame and outrage piled up from all corners.

The state blamed some “counties engaging in poor planning, limited training, and [failures] of leadership.”

Some counties, understaffed and overwhelmed by a crush of in-person voting, blamed the state for failing to provide them with adequate support.

Democrats called out Republican policies, while Republicans highlighted many problems in Democrat-led communities.

Stuck in the middle were scores of Georgia voters who waited upwards of four hours to vote after inexperienced poll workers struggled with a new $104 million touchscreen voting system, coronavirus-induced polling changes relocated 10% of the state’s polls and failures in the constantly-touted absentee by mail system led many to vote on Election Day.

RECAP: Georgia Primary Live Updates: Some Polls Stay Open Later; Finger-Pointing Over Problems Begins

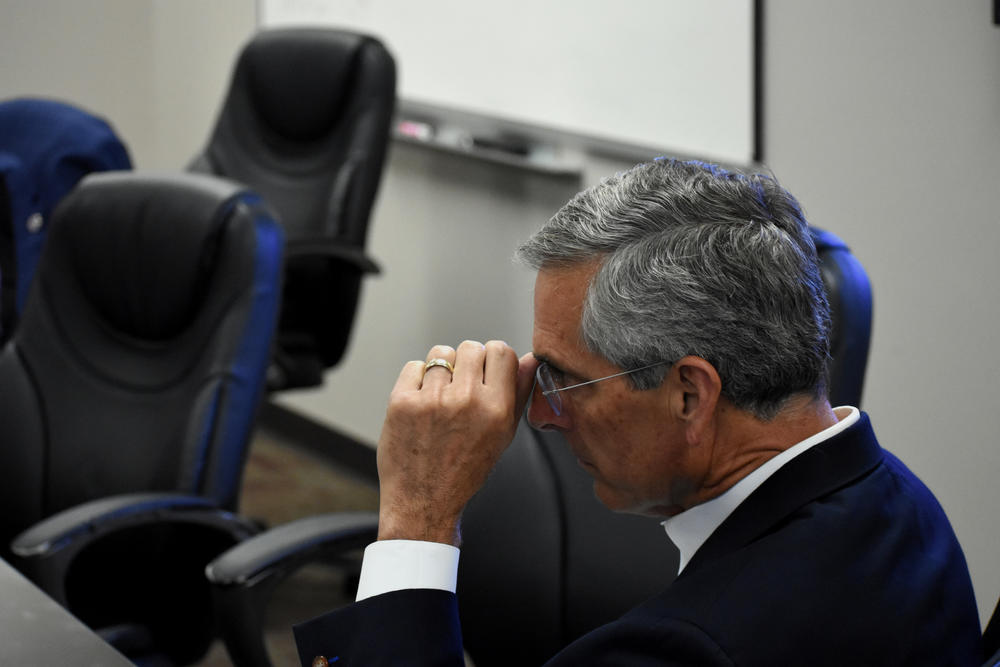

Around 5 p.m. in a nondescript conference room across from the state Capitol, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger was listening to a rundown of polls kept open by judicial order because of issues and delays.

Staff members relayed voting numbers and reports of lines, and Georgia’s chief election official stepped out of the room to paint an optimistic picture of a voting day clouded by headlines questioning the state’s competency.

“We’re excited about great turnout in the absentee process, great turnout in 16 days of early voting and it looks like we’re having strong turnout again today,” he said. “It’s a good day for Georgia.”I asked @GaSecofState what he would say to people who have concerns about Georgia’s elections today. #gapol

Here’s what he said: pic.twitter.com/ov8cpZbxOh— stephen fowler // voting+georgia politics (@stphnfwlr) June 9, 2020

More than 1.3 million people voted early, including a million absentee ballots returned ahead of Tuesday. But many voters reported never receiving their absentee ballot, or never had their applications processed, driving an unknown number of would-be early voters to their polling places.

In precincts across the state, especially metro Atlanta, disastrous delays at the polls were destined to start before the first ballot was cast Tuesday.

CONTEXT: Voting In Georgia’s June 9 Primary? Here’s What To Expect

For months leading up to the vote, GPB News and the Georgia News Lab reported on the challenges election officials faced in preparing for a primary mid-pandemic, including longer lines because of social distancing, a shortage in poll workers and polling places and struggles with a new voting system unfamiliar to many volunteers and voters alike.

Many of those were on full display Tuesday.

At the Cross Keys precinct in DeKalb County, voting halted for several hours after poll workers had issues with the ballot-marking devices – and then ran out of backup paper ballots after just 20 voters. Only four out of 12 poll workers showed up to work.

80-year-old Anita Heard was frustrated.

“America has gotten to the point that we are now taking the liberties of people, even voting, from them,” she said. “How can we do this? We’re supposed to be the best, and we have proven ourselves at this time to be worse than any country alive.”

Her frustration was echoed in person and on social media and at polling places statewide as similar stories emerged: some Gwinnett County polls did not have equipment delivered, Fulton County poll managers had incorrect access codes to activate machines and in Bibb County voters were given backup paper ballots with the wrong races on them.

MORE COVERAGE: Voting and COVID-19 in Georgia

Even at polls with no reported issues, increased turnout and fewer voting machines meant hours-long lines.

At Lang Carson Recreation Center in the Reynoldstown neighborhood of Atlanta, 110 people voted by 10:15 a.m. – and this reporter waited in line from 6:50 a.m. until that time to cast his vote.

More than 350 people were in line at Park Tavern in Atlanta, where a pair of poll closures led to 16,000 active registered voters being assigned to vote at the restaurant and event space. By 6:45 p.m. volunteers passing out pizza and water were telling voters to still expect nearly three-hour wait times, and a poll worker estimated more than 3,000 had cast their ballot.

Current Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms and former mayor Kasim Reed called attention to delays in majority-black precincts in South Fulton early Tuesday morning, highlighting racial and economic disparities in some poll locations across metro Atlanta.

In the last eight years, 10 metro counties added more than a million voters, primarily non-white, to the voter rolls. Most of them failed to add polling places, with some closing polls even before coronavirus hit.

Several counties sought judicial orders to keep polls open past 7 p.m. to accommodate locations that were delayed in opening or experienced lengthy lines.

Democrats and Republicans alike spent most of the day lobbing escalating calls for investigations into the day’s election and lambasting the other party for their alleged roles in the voting problems.

Raffensperger announced his office would look into voting in Fulton and DeKalb counties, where the majority of complaints were located.

House Speaker David Ralston (R-Blue Ridge), an opponent of expanded mail-in voting, issued a statement calling for an investigation of voting – specifically in Fulton County – and said the legislative branch “has an obligation to go beyond the finger-pointing and get to the truth” about what happened.

Later, Sen. Jen Jordan (D-Atlanta) and Rep. David Dreyer (D-Atlanta) wrote that “despite the finger-pointing, there have been failures at all levels” and condemned the state’s aggressive stance towards county officials that oversaw long lines and errors.

“While there is little doubt that local officials have made mistakes, it is ultimately the role of the Secretary of State to ensure the integrity and efficacy of the voting process.”

With a widely-watched Democratic U.S. Senate primary and a national reputation for voting problems, Georgia quickly became a case study for how voting could go wrong in the coronavirus era.

As results begin trickling in and the dust settles on Election Day, months of preparation and warning about voting issues becoming a reality was enough for some voters like Anne White in Macon to change plans for the November election.

"Next time I'm going to do absentee," she said. "This is a mess."