Section Branding

Header Content

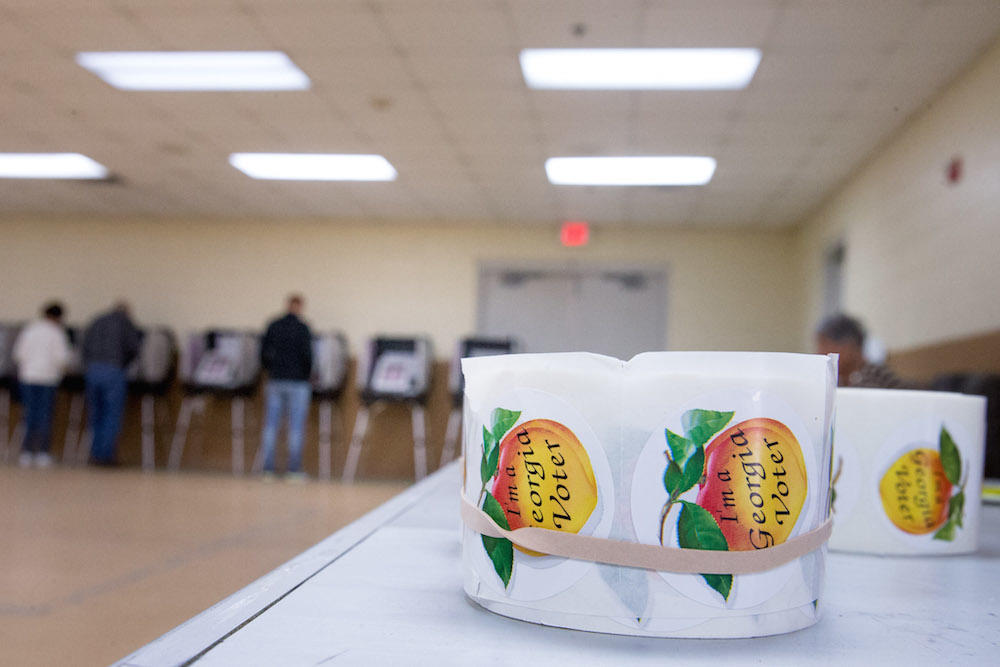

Lawsuit Seeks To Stop Georgia From Implementing New Ballot-Marking Devices

Primary Content

One day after a ruling was issued that requires Georgia to ditch its outdated touchscreen voting machines in 2020, a group of voters asked a federal judge to block the state from replacing it with a new $107 million ballot-marking device system.

Thursday, U.S. District Court Judge Amy Totenberg ordered the state to move to a paper ballot-based voting system after this fall’s municipal elections and to pilot hand-marked paper ballot voting in some elections this fall.

The new system selected by the secretary of state’s office satisfies that first order, as Dominion Voting Systems’ Image Cast X BMD combines a touchscreen tablet with a printer to produce a paper-based summary of a voter’s selection with a QR code that is then scanned and stored.

Totenberg expressed skepticism about the state’s ability to implement the new system in time for the March 24, 2020, presidential primary, and also asked officials to develop a plan to implement hand-marked paper ballots next year as a backup in case that deadline is not fully met.

The latest complaint, filed Friday by one set of plaintiffs in the ongoing Curling V. Raffensperger lawsuit, alleges that the new voting system Georgia is moving towards has the same security vulnerabilities as the state’s current outdated direct-recording electronic machines.

In the amended complaint, lawyers for the plaintiffs point to testimony during a July 2019 hearing from experts hired by the state that highlighted cybersecurity risks within the secretary of state’s office as evidence these vulnerabilities exist.

RELATED: Judge Says Georgia Must Scrap Outdated Electronic Voting Machines After 2019

Following that hearing, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger announced the intent to award the $107 million contract for the state’s voting system to Dominion, with up to six counties piloting the machines in this November’s municipal elections.

Raffensperger touted the security and auditability of the new voting system, calling elections security his office’s “top priority” and pointing to language in this year’s omnibuss elections bill HB 316 that spells out processes for audits.

The plaintiff’s lawyers disagree, writing in the complaint that the BMD’s reliance on a QR code “does not provide a meaningful way for a voter to audit their vote.”

In the new system, the QR code is what is scanned and tabulated for election night results, but the human-readable text summary printed on the ballot would be used for audits or recounts.

The other plaintiffs in the case with the nonprofit Coalition for Good Governance also indicated they would challenge the use of BMDs in next year’s elections.

In Thursday’s order, Totenberg denied a request to move several hundred municipal elections happening this fall to a hand-marked paper ballot system, citing concerns about the state’s ability to implement that system and the new BMD system at the same time.

But she noted that her ruling was only about the usage of the state’s current system and not about the new one, and extensively documented the past problems with the state’s elections administration and how they have “previously minimized, erased or dodges issues underlying this case.”

“The past may here be prologue anew – it may be “like déjà vu all over again,” she wrote, quoting Yogi Berra and setting the stage for future arguments by the parties about this new complaint.