Section Branding

Header Content

Olympian Elana Meyers Taylor Is Saving Her Brain For Future Female Athletes

Primary Content

For bobsledder and Georgia native Elana Meyers Taylor, the Olympics are a culmination of more than a decade of work.

She won three medals including silver at this year’s games in Korea.

But Taylor’s Olympic career almost ended in 2015 after she suffered a serious concussion.

GPB's Taylor Gantt shares the story of Georgia Olympian Elena Meyers Taylor

Now the bobsledder is pledging her brain to science to help understand how concussions affect female athletes.

From a young age Taylor says she wanted to be an Olympian for Team USA, but she wasn’t always sure what sport was going to get her there.

After a softball tryout didn’t pan out her family suggested giving bobsledding a try.

“My parents had actually seen bobsled on TV, and said ‘why don't you try this one?’” Taylor says.

That curiosity led to a tryout at Lake Placid, and ultimately, a brilliant bobsledding career for Taylor, which includes a bronze medal in Vancouver and a Silver in Sochi.

But a year after bringing home her second medal, Elana suffered a life-altering injury during a 2015 run in Germany.

“My sled flipped and I hit my head on the ice.” Taylor recounts. “That concussion basically changed a year of my life. I had symptoms for a while after that and it really affected how I was able to not only perform in a bobsled, but my day to day living.”

Taylor experienced the normal symptoms of a concussion: headache, dizziness, and fatigue. But long after the crash, she discovered that her mental state had taken a turn for the worse.

“I became somebody, somebody completely different. I was losing it on things that didn’t even matter, things that didn’t even make sense.”

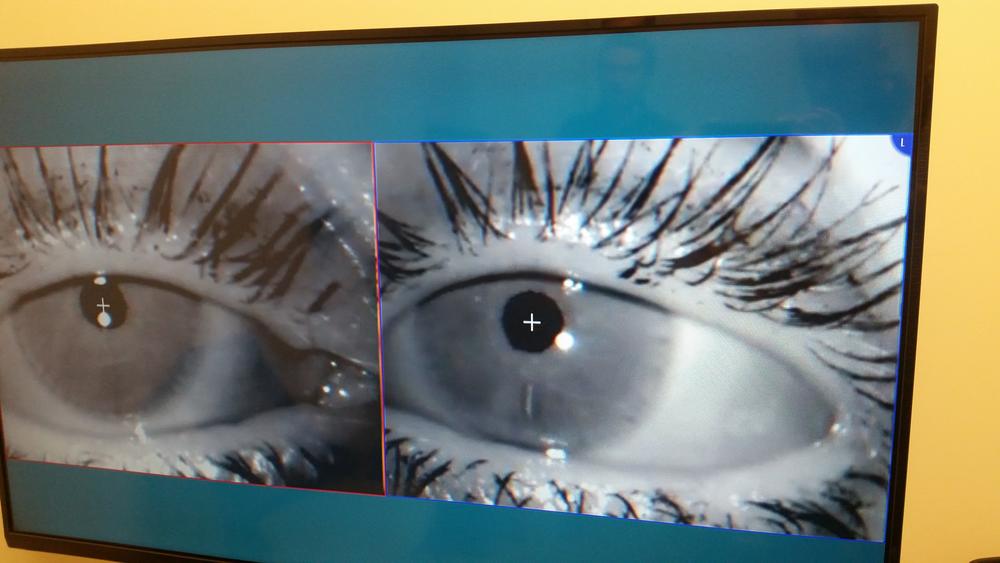

Taylor turned to the doctors at the NeuroLIFE Institute to find a chiropractic solution to her problem.

There, she met Ryan Cedermark, who directs the Institute’s Vital Life Health Center in Atlanta.

He says athletes who suffer brain trauma often deal with damage to their balance centers, which can have physical and mental side effects.

“If your balance is off and you’re getting miscommunication from these tissues in your feet, your legs, and your back, you’re going to get some scrambled, misinformation going into the brain.”

The team at NeuroLIFE worked with Taylor to regain her mental balance with several exercises and tools, including a large, rotating chair called the GYROSTIM, a device that almost works like an astronaut training tool.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MpShQZMVmlo&feature=youtu.be&ab_channel…

Once strapped in, the machine pivots the patient in different directions while they attempt to tag targets with a laser pointer. The exercise works to re-train reflexes and coordination that can be lost after a brain injury.

With the center’s help, Elana finally began feeling like herself again. This spring, she earned her third Olympic medal at the Winter games in South Korea.

But last year, the overdose death of teammate Steve Holcomb got Taylor thinking about her own legacy after sports.

“For me, I really thought about my history with concussions and what I could to help other people,” Taylor says.

Soon after, she made the decision to donate her brain to the Concussion Legacy Foundation, a group that studies Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, the brain disease associated with concussions.

“We know very little about how concussions work in the female mind, so for me, leaving my brain specifically felt like I could do more for my legacy.”

The world’s largest CTE Center, the Brain Bank at Boston University, says out of the hundreds of donated brains they’ve received, less than 10 are from female athletes.

Donations like Taylor's could prove invaluable for shortening the research gap between men and women.

Steve Broglio, who directs the Neurotrauma Research Lab at the University of Michigan, says more data on head injuries is key to discovering the root causes surrounding CTE.

“We don’t have a strong understanding of CTE, why some people get it, why some people don’t. I think a lot of research needs to focus in that area, and then we can start targeting those things that do result in the disease.”

As for Taylor, her injury won’t end her Olympic dream anytime soon. She plans on earning a fourth trip to the Winter games in Beijing in 2022.

“I absolutely love what I do, I’m healthy, I’m still young enough to compete at a very high level,” Elana says. “I want to give it another four years and I’m going to do everything I can to make sure I’m there in 2022.”