Section Branding

Header Content

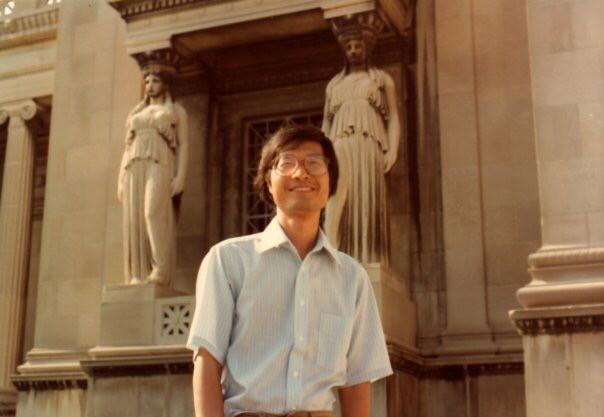

Commentary: My Dad The Hero

Primary Content

Happy early Father's Day to all the dads out there. If you haven't decided what to get your father, consider a trip down memory lane. Bee Nguyen of Atlanta has taken the time to reflect on how her relationship with her dad has changed. She shares this dedication to a man has lived in two different worlds -- one as a middle-class dad in America, the other as a poor child in Vietnam.

My dad lives for his jobs.

You can tell by his hands. They’re spotted, several shades darker than my mom’s. They’re labored hands, not the ones I picture for either a pharmacist or a chemical engineer. They are more like the hands of a man once jailed in reeducation camp in Vietnam in the 1970s, starved, condemned to hard labor and forced by his captors to recite Communist doctrine.

When I was a child, his presence in our household was marked by the absence of a second car in the garage, the empty space occupied only after my bedtime. From beneath the covers, I listened for the faint thuds of his footsteps, the jostling of his keys and the bleep of the house alarm, alerting our bilingual family dog of his arrival: Bố ve roi!

My father has always worked two jobs – just like he always votes Republican in federal elections, and always mows the lawn on weekends. Last year he abruptly quit his second gig at the Veteran’s Hospital, freeing up his Saturdays and Sundays for the first time since I moved away for college. Now when I make the two-hour drive to my family’s house in Augusta, I am startled to see his trusty Honda Accord tightly parked in the cluttered garage.

My dad is bored now, his brain dulled by his iPad, his identity ensnared by middle class America. When he had two jobs, he at least didn’t have to worry about finding a hobby like golf, or hiding his general distaste for sports, or trying to relate to his five daughters. Instead, he would fill prescriptions, dole out medicine and stand on his feet for ten or twelve hours at a time, making it easy to return home and fall asleep on his recliner every night of the week.

He has never really enjoyed his work, though. His jobs distracted him from grieving for the parents he left behind in Vietnam, or wondering if his daughters might show him more respect had they been raised more traditionally in his home country. His jobs provided him with titles and accolades he could attach to his name or hang on the walls of his office. Nhuan Nguyen, Doctor of Pharmacy or Nhuan Nguyen, Ch.E. His jobs created for him routine, like the security of putting on his white lab coat, name tag fastened near the lapel.

But even with 80-hour workweeks followed by fitful sleep, there were still increments of time my dad could not fill. In these spaces, he told us stories about prison camp and the way he would break up blocks of salt to share with his cellmates, pinching with their fingers portions of white rice given to them twice a day. He recalled with laughter the unbearable hunger, how he would walk the two miles to school, where he performed at the top of his class, numbing the pain he felt from the shortcomings he could not change. Once he arrived in America at the age of 30, he did the same thing. And with almost no language skills, he managed to graduate in two and a half years, earning his degree as a chemical engineer.

The award, the merit my dad cannot frame for display, is his status as a hero in our eyes. It’s the job he can’t retire from — the one that will unburden him from the stress of keeping his American identity intact. It pays him far more than any of his advanced degrees. And it can’t be stripped away in America or in Vietnam.

Bottom Content