Section Branding

Header Content

Deluxe: Freedom Seekers - The Untold Story of The U.S. Colored Troops

Primary Content

Nearly 200,000 Black soldiers fought for their freedom in the Civil War. And their families risked everything alongside them. Host Chuck Reece explores the legacy of these soldiers through the powerful, historical poetry of Frank X Walker, and with the help of Pulitzer Prize-winner Edda Fields-Black, historian Holly Pinheiro Jr. and Steve Phan, Park Ranger at the Camp Nelson National Monument. This episode brings to light the struggle, resilience, and enduring impact of African American soldiers in Southern history.

TRANSCRIPT:

Chuck Reece: I was not quite a teenager yet when a singer from Florida named Jim Stafford started scoring hits on the Top Forty radio. Novelty songs were his thing. His biggest hit was called “Spiders & Snakes,” a song about a boy who had a girl he wanted to woo——whose name was Mary Lou. And his method was to show her a frog he’d caught in the local swimming hole. Turned out that neither frog, nor spider, nor snake could woo Mary Lou.

But it was his first hit that always refused to leave the recesses of my brain. It was called “Swamp Witch,” about a magical woman named Hattie who lived way back in a Florida bayou. Stafford’s opening lines and their description of the swamp caused my timbers to shiver.

MUSIC: Jim Stafford - "Swamp Witch"

Black water Hattie lived back in the swamp

Where the strange green reptiles crawl

Snakes hang thick from the cypress trees

Like sausage on a smokehouse wall

Chuck Reece: Could not get that out of my head. Snakes, dozens of them, hanging from tree limbs, like sausages in a smokehouse. One of my uncles had a smokehouse. I knew what that looked like. But snakes?

My brain had been imprinted. The swamp was a very scary place, full of dank smells, dense fog, and dangerous reptiles. Thank goodness, this never turned into an outright phobia as I grew up. But it did turn into a metaphor for the place where I grew up——the American South. Southern history is a swamp, metaphorically. Millions of Southern school kids in my generation and later were taught false versions of our region’s history. Because the daughters of this and the sons of that believed the truth should be obscured, hidden. Relegated to the swamp.

But in every corner of the South, the truth also lingers in the air. Sometimes celebrated, sometimes forgotten, and sometimes, purposefully muffled.

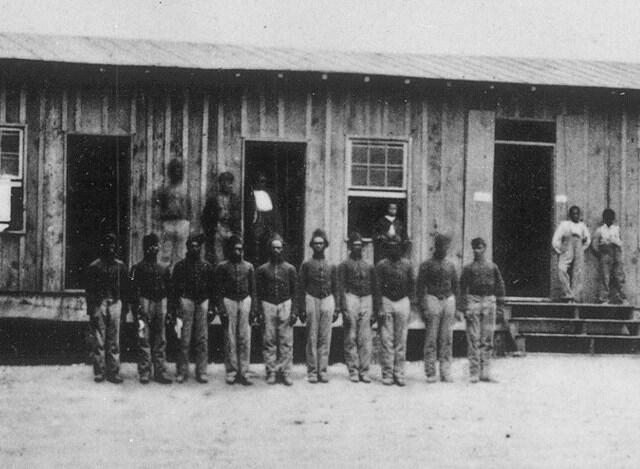

One such truth is the story of the U.S. Colored Troops. The Colored Troops comprised nearly two hundred thousand Black men, most of them formerly enslaved, who joined the U.S. Military to fight against——and ultimately defeat——the Confederacy in the Civil War.

Today, we intend to bring the story of the U.S. Colored Troops out of the swamp——their fight for freedom from slavery, the families they carried with them, and their legacy, which still shapes the culture and history of the South.

Chuck Reece: To tell you the story of the USCT, this month on Salvation South Deluxe we will introduce you to:

- Two fascinating historians: Holly Pinheiro of Furman University in South Carolina, and Carnegie Mellon University in Pennsylvania, and Edda Fields-Black, whose book on this history just won the Pulitzer Prize.

- Steve Phan, the chief of interpretation and education at the Camp Nelson National Monument in Nicholasville, Kentucky. Camp Nelson was the largest recruitment and training center for the U.S. Colored Troops, and

- Frank X. Walker, the legendary Kentucky poet, whose latest book turned the real stories of Colored Troops soldiers and their families into poetry.

THEME MUSIC UP

Chuck Reece: I’m Chuck Reece, and welcome to Salvation South Deluxe, a monthly series of in-depth pieces that we add to our regular podcast feed. On Deluxe, we try to unravel the untold stories of the Southern experience by letting you hear the authentic voices of Southerners who make this region truly unique.

THEME MUSIC OUT

ACT ONE

Chuck Reece: In the summer of 1862, the second summer of the Civil War, the United States Congress passed two laws that led to the formation of the U.S. Colored Troops. The first was the Confiscation Act, which authorized Union officers to free enslaved Blacks, and the Militia Act, which allowed President Lincoln to enlist free Blacks and former slaves in the U.S. Army.

Then, on New Year’s Day of 1863 President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which set forth, in Lincoln’s words, "that on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State … shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

The Confederate States did not comply, of course; they were trying to form their own nation. Some states, like Kentucky, were afraid to leave the union, but also refused to free their slaves. Five months later, the U.S. government made clear its intention to bring emancipated slaves into the fight. On May 22, 1863, the United States War Department issued General Order Number 143, which established the Bureau of Colored Troops to organize, recruit, and oversee African American soldiers serving in the Union Army during the Civil War.

From a practical perspective, those events of early eighteen-sixty-three told enslaved men this: If you can escape from your owners and reach Union lines, you can enlist in the U.S. Colored Troops and win your legal freedom.

Dr. Holly Pinheiro: The United States needs those people, and they needed those refugees during the Civil War to wage and win a war, even if they don't want to provide them at times with resources, with protections, with food, with money, and yet dangling out "Your men should fight and die for this country.” And so for some of those refugees, they're understanding that they have power, a lot of power.

Chuck Reece: That’s Dr. Holly Pinheiro at Furman University. In 2022, Dr. Pinheiro published a book called The Families’ Civil War: Black Soldiers and the Fight for Racial Justice, a book that provides us with a wealth of details about members of the U.S. Colored Troops. But the book goes a step further to help us understand how enslaved people’s service in the USCT was part of the longer struggle for racial justice.

African American soldiers were already in place on the Union side before General Order Number 143 made the USCT official. And here, Harriet Tubman becomes part of the Colored Troops’ story. Most of us know about Tubman’s role in the Underground Railroad, which help enslaved people reach relative safety after they escaped. Fewer of us know about Tubman’s role as a strategist for the Union Army.

Dr. Edda Fields-Black: She was the architect and leader of one of the most successful and dramatic Union raids in the Civil War.

Chuck Reece: That is Dr. Edda Fields-Black of Carnegie Mellon University. And the raid she speaks of is the Combahee River Raid. Her 2024 book about the raid was called Combee: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom During the Civil War. It won the Pulitzer Prize for history.

The raid began on the evening of June 1st, 1863 and ended the next day after the Union Army invaded Confederate plantations along the Combahee River in the South Carolina Lowcountry. During the night, the U.S. Army destroyed homes and rice mills on those plantations and liberated seven hundred enslaved people.

Dr. Edda Fields-Black: I think it's safe to say that the Combahee raid was built on Tubman's intelligence, intelligence that she gathered. I think it's safe to say that she was a part of reconnaissance missions on the company plantations before the raid.

Chuck Reece: On that June evening, Tubman and Union Army Colonel James Montgomery set out from Beaufort, South Carolina, on a fleet of Union gunboats. I’ll let Dr. Fields-Black explain how the raid proceeded.

Dr. Edda Fields-Black: We know, and I'm able to document in Combee, that, number one, she led a group of 8 or 9 spies, scouts and pilots. This was her ring. This was her spy ring, and she commanded them. And she took her men to the Combee and on to the plantations. They found the enslaved men who were forced to mine the company with torpedoes, and they came back with likely the third Rhode Island Heavy artillery officers. And Tubman stayed with the women and children, the spy scouts and pilots, and the officers went up and got them in again and took them back to the site and defused the torpedoes. And this opened up the Combahee River to the Union boats.

During the raid on June 1st, 1863, her men, her spy scouts and pilots, piloted Colonel James Montgomery up the Combahee River and went to onto the plantations. So she's engaged in the planning and the execution, and she's engaged in the leadership of this spy ring.

Chuck (from interview): Why don't people know about the Combahee River Raid? Why isn't that as much common knowledge as the Underground Railroad?

Dr. Edda Fields-Black: That's a good question. … But the Underground Railroad is also pretty poorly documented——and documented mainly by abolitionists, white abolitionists and some Black ones as well, who, you know, worked in various capacities, who risked their lives and their livelihoods in various capacities helping freedom seekers get to freedom. Civil War literature didn't really take Tubman seriously. Her Civil War service is not documented in the official military record. Her role in the Combahee raid is not documented in the official military record.

Chuck Reece: That history was also obscured by the pre-Civil War willingness of the U.S. Government to make concessions to the slave states of the South. People who study African American history always confront what Dr. Fields-Black refers to as the Eighteen-Seventy Brick Wall. Tracing the lineage of Black Americans back beyond that Wall is very difficult.

Why? Because every U.S. Census before the Civil War did not count Black people by name. The 1870 Census was the first time, in fact, they were counted as humans. Before then, Black people were listed in the Census only as the property of white people, identified by first name only. One reason her book won the Pulitzer was the research Dr. Fields-Black did on the other side of that wall.

Dr. Edda Fields-Black: I started at the brick wall. I got … as far back as we could go. And you know those people who are listed in the 1870 census. This being the first federal document in which the majority of African American ancestors are listed by first and last name. And in the plantation sources, they are listed overwhelmingly by first name. And one of the things I find in Combee is that enslaved people had last names. They certainly had last names in the community that they used and that they identified with, and … everybody had a history of why they chose their name.

Chuck Reece: But before Eighteen Seventy, the last names they chose were never documented. The enslavers had no intention of allowing the enslaved to own anything at all, not even their names. The pain of that literal identity theft still lives in the culture of the South.

MUSIC: Lead Belly - "There's A Man Goin' Round Takin' Names"

There’s a man goin’ ’round takin’ names. There’s a man goin’ ’round takin’ names. He takin’ my father’s name. And he left my heart in vain. There’s a man goin’ ’round takin’ names.

Chuck Reece: That’s Huddie Ledbetter——Lead Belly——in a recording from the nineteen-forties. A few years after that “Swamp Witch” song scared me to death, I watched a TV miniseries called Roots, which was based on the late African American writer Alex Haley’s novel of the same name, which he based on his research into his own family’s history.

A scene in that series showed a young African man named Kunta Kinte, kidnapped and brought as a slave to America, tied by his wrists to a rack, his feet dangling above the ground. Asked his name, he replies, “Kunta. Kunta Kinte.” His enslaver says, “Your name is Toby.” Kinte is repeatedly whipped until he agrees.

Such were the men goin’ ’round takin’ names.

Dr. Fields-Black found a way over the 1870 Brick Wall by doing research into her own family’s history. Enslaved men who escaped and joined the Colored Troops were entitled, just like white Union soldiers, to military pensions, which meant that their names appeared in the Army’s pension records from the 1860s.

Dr. Edda Fields-Black: I also went down a rabbit hole trying to sort of trace my family, and at the time, thought that this was totally separate from the book I was writing. … I mentioned Daddy was born a mile or two from where the raid took place. I was … charged with some family business by our family patriarch who had passed away. I actually ended up going to the international African-American Museum Center for Family History.

Chuck Reece: A woman named Toni Carrier, a friend of Dr. Fields-Black, is the director of the Center for Family History at the International African American Museum, which sits on the site of Gasden’s Wharf in Charleston, South Carolina. Historians believe that as many as forty percent of the Africans brought here in chains during the height of the slave trade first touched American soil at Gasden’s Wharf.

Dr. Edda Fields-Black: I went with what I knew about our family. I was looking for the Fields family, and my cousin had been going to the census and going back to our earliest known ancestor in the 1870 census, and I took it to my friend Tony Carrier, who was the director at the time of the center for Family History, said, Tony, please help me. And she looked at it and she said, oh, that's Hector Fields. He's a Civil War veteran in Beaufort County. She helped me to find out that, yes, that actually was my great-great-great grandfather, who joined the second South Carolina Volunteers in March of 1863. The whole family history was laid out in the pension file.

Chuck Reece: Did you pay close attention to what she just said? She did not find only the records of her great-great-great-grandfather Hector. She also found the “whole family history." This is because when enslaved men escaped and made it across the Union borders so they could enroll in the Colored Troops, most brought their families with them. Which meant that the Army camps where the Colored Troops mustered also became refugee camps for their families.

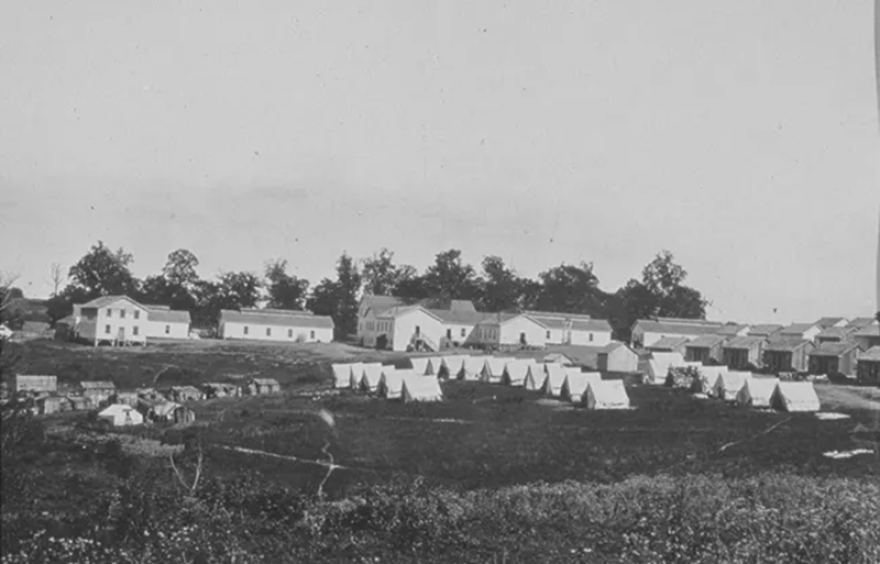

The largest of those was Camp Nelson in Nicholasville, Kentucky. Are you thinking, Kentucky? Why would the Union army muster the Colored Troops in a Southern state? Well, you have to remember that Kentucky never seceded from the Union. And from 1862 onward, the state was firmly in the control of the U.S. Army.

Dr. Holly Pinheiro: Camp Nelson is a big deal for the United States. Firstly, because that was one of the largest military bases where you had USCT regiments training.

Chuck Reece: Dr. Pinheiro’s research also covered USCT camps that were located farther north, but he says Camp Nelson is unique among the military bases where the Colored Troops mustered.

Dr. Holly Pinheiro: What makes Camp Nelson very important and unique from northern camps ... is they were inclusive spaces in the sense that they weren't just for soldiers. Camp Nelson provides opportunities for empowerment. Women were there. Women had prominent roles there. They supported the United States effort. Children were there. It's not just that soldiers were there. Communities were there. Families were there. Families were formed there. Families dissolved there. People reconnected.

Chuck Reece: But Dr. Pinheiro is quick to point out that what he just said should not make you think Camp Nelson was all sunshine and roses for escaped slaves. After this short break, we’ll take a little trip to Camp Nelson, so we can show you why.

You’re listening to Salvation South Deluxe.

MIDROLL BREAK

ACT TWO

Chuck Reece: Steve Phan is the chief of interpretation and education at the Camp Nelson National Monument. His work, helping visitors to understand the lives of the U.S. Colored Troops and their families who were refugees here, is personal to him.

Steve Phan: I'm a son of refugees. I think about my parents all the time when I'm at Camp Nelson. … My father was only 19 years old when he fled Vietnam in 1975 right before Saigon fell.

Chuck Reece: After learning from Steve Phan, I’d have to say that no Southern state embodies all the complexities and conflicts of the Civil War era more fully than Kentucky.

Steve Phan: When you think about Kentucky, you think of some of the big battles that took place here in Perryville and Richmond, Munfordville. You think about the presidents that were born here. Lincoln and Jefferson Davis were both born in Kentucky, right? You'll hear about Confederate raids and things like that, but you don't hear too much about Camp Nelson. And... for us, it's a great opportunity to engage with visitors, right, on the complexities of this site. And it kind of is symbolic of the complexities of this state, the paradox of Kentucky during the war.

One of the first things that we often hear from visitors is they're like, Kentucky was a Confederate state, right? And we hear that all the time. And, no. Kentucky was a border state, right? It was a loyal slave state, like Missouri, Maryland, and Delaware. and Kentucky will hold on to the institution of slavery as long as they can, which will impact the lives of thousands of people, including enslaved people, men that will join the U.S. Army, their families who are refugees at places like Camp Nelson as well.

Chuck Reece: If I made you think Kentucky’s refusal to secede and join the Confederacy was in any way about morals, I apologize.

Steve Phan: White Kentuckians saw loyalty to the union in the United States as the best way to protect the institution of slavery. And Lincoln understands that very, very well, as does his administration. And he's very... Cautious about how he treats Kentucky during the Civil War.

Chuck Reece: Although Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation and formally recognized the U.S. Colored Troops in 1863, the U.S. Government did not allow the enlistment of African American men in the state of Kentucky until 1864.

Steve Phan: So in 1864 is when the Army lifts all restrictions and they authorize the enlistment of African-American men in Kentucky into the US Army, known as the US Colored Troops, USCT. They'll organize eight recruiting stations across the state, the largest being at Camp Nelson, where over 10,000 Black men will be assigned to a Camp Nelson regiment, one of the eight black regiments organized here. These are freedom seekers. They're trying to escape slavery So they're coming with wives, children, other family members. There's a lot of unaccompanied … minors. Anyone that's trying to escape slavery is coming to places like Camp Nelson, because the army is here at least.

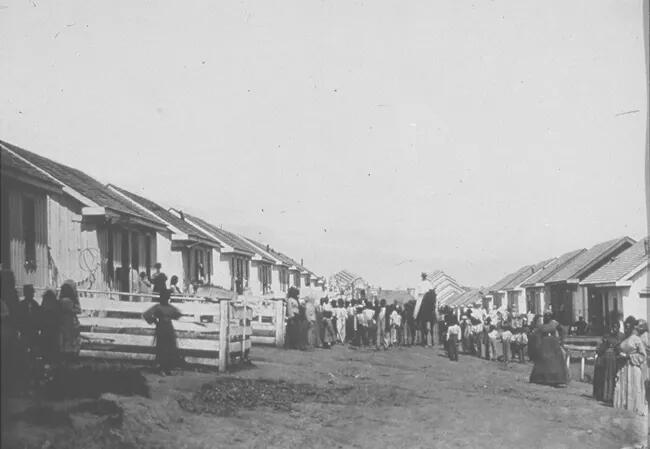

And this is the paradox, the incredibly difficult part of Camp Nelson, where you see triumph and tragedy at the same time. When the men join the army, they free themselves. We call it self-emancipation. And so Camp Nelson becomes this freedom center for thousands of people. But what about their families? Literally, their wives and children. What happens to them? Well, they're literally called refugees.

Chuck Reece: If you were writing a movie about this story and you were looking for a happy ending, you might think Camp Nelson would be the turning point.

Alas, American history is not that easy.

Dr. Holly Pinheiro: Looking at Camp Nelson actually provides a way to realize the precarious situation that the Self Emancipated put themselves into hoping to reestablish their ... lives as freed people, recognized as human beings, and also having to realize that the camp didn't necessarily bring with it all of the freedoms that they hoped for. And so they entered into circumstances that were difficult for them.

Chuck Reece: Difficult and complicated. Men who enlisted in the U.S. Colored Troops were officially emancipated from slavery. But not their families. Still, the soldiers’ families came to Camp Nelson, hoping to find freedom.

The enlisted men’s families formed refugee camps outside the military camp.

Steve Phan: They're in a very precarious situation. They don't really have a status, or, in a way there, they would be considered runaways, you know, because slavery is still legal here. It's protected by state and federal law.

Chuck Reece: And the white Union officers? You couldn’t call them racially enlightened. They did not see the families, the refugees, as a humanitarian challenge. They saw them as a problem.

Steve Phan: The officers here believe that these people are gonna bring disease and break down discipline and things like that. … So they don't wanna allocate supplies and food and things that.

Chuck Reece: Which meant that Union troops repeatedly and forcibly expelled the refugees and destroyed their camps.

Steve Phan: Eight or nine times throughout the remainder of the year, the army will forcibly expel refugees from Camp Nelson. … There’s multiple expulsions.

Chuck Reece: So put yourself in the shoes of a formerly enslaved man who has risked his life and the lives of his family, hoping to find freedom by enlisting in the U.S. Colored Troops. While you are inside Camp Nelson, the same army you have enlisted in is outside the gates, driving away your family.

The last expulsion, on November 23 1864, was the deadliest and largest. It was during a winter storm.

Steve Phan: Over 400 refugees are expelled and it's horrific. These people are expelled, and within a few days, the order is rescinded but the impact is dramatic, unfortunately, and over 100 people die as a result, including you know family members of U.S. Colored Troops.

Chuck Reece: Only after this disaster does Lincoln’s government move to change the situation at Camp Nelson. Lincoln did not want enslaved men who had escaped to stop enlisting in the U.S. Colored Troops because they feared for their families’ safety.

Steve Phan: This will spur the federal government to establish the Home For Colored Refugees at Camp Nelson, which happens around this time. 1865, the Army will change policy allowing refugees, all freedom seekers to come into places like Camp Nelson.

On March 3rd, 1865, Congress passes legislation which emancipates the wives and children of Black soldiers. And one of the reasons why they’re doing this, they literally call it to “promote the efficiency of the military.” They’re realizing that men are not enlisting because they can’t take care of their families, right?

Chuck Reece: One month after the emancipation of the families, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrenders in Appomattox, Virginia.

Two months after the surrender, on June 19th, 1865, word finally gets to slaves in Galveston, Texas, that they are now free. Juneteenth.

Slavery is not officially abolished in America until the ratification of the 13th amendment to the Constitution, which states, ”Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

We had thirty-four states then, which meant twenty-seven had to ratify the amendment for it to become part of the Constitution. The twenty-seventh, Georgia, ratified the amendment on December 6th, 1865. Voting in various states continued for another month, and five more states voted to ratify. But there were some holdouts.

Steve Phan: December 6 1865 is when the 13th amendment is ratified. Kentucky does not ratify the amendment until 1976. We have a timeline in our visitor center, and people always point that out. They're like, do you mean 1876? We're like, No. 1976. So just think about that in context.

Chuck Reece: I can’t stop thinking about it. A lot of folks believe stubbornness is part and parcel of Southern culture. Sometimes, that’s a good thing. Sometimes, it’s not. Not at all. When the amendment came before the Kentucky legislature in 1865, it was voted down. Instead, the legislators passed a resolution that claimed——and I quote——“self-interest will induce Kentucky…to treat her negro population with perfect justice.”

Hmmmm.

The last state to ratify the 13th amendment was Mississippi. In 1865, its legislature asserted that the federal government should compensate Mississippi enslavers for the loss of their ... property. That demand was never met.

The state’s symbolic ratification didn’t happen until 1995, when both houses of the Mississippi legislature unanimously voted to ratify the amendment. Despite those unanimous votes, state officials never sent the required certification to the Office of the Federal Register in Washington. When the error was finally corrected——almost eighteen years later—the Mississippi government maintained that the delay had been nothing more than a clerical oversight.

Mississippi finally submitted its certification--formally attesting that the state had ratified the 13th amendment--on February 7th, 2013.

One hundred and forty-seven years, two months, and one day after the amendment became law.

ACT THREE

Frank X. Walker:

“The Big Breakup”

We was more than a little salty to find out

we’d been emancipated mo’ than two whole years,

that masta crawled home from the war and decided

to keep our freedom to himself.

I remember the urge to just set down and do nothing

for a spell, just to see what it feel like.

Then they told us we can now get paid for our labor.

But when we find out how little money it was,

a handful of us decided what we wanted to do

with our freedom was go find our beloveds

that was sold off or had run away.

Most of us had missing family we ain't seen

since who knows when and was willing to walk

to Kingdom Come and back just to hold them again.

Working for just enough to keep you alive or laboring

to put sore eyes on loved ones that made life

worth living was a easy choice. What freedom come to mean was to finally own land,

to build our own schools and businesses,

to travel unrestricted, to simply enjoy the right to hold

the hands, wipe the eyes, and kiss the cheeks

of the people you love most in this world.

To be able to close your eyes and rest while you pray

for the strength to make it through whatever God got next.

God bless every fallen soldier. So many fought

for our freedom. More than 23,000 Kentuckians.

This is our Jubilee. This is our Emancipation Day.

This be our glorious Juneteenth.

Chuck Reece: That was Frank X. Walker, legendary Kentucky poet and founder of the Affriliachian Poets. The poem you heard Frank read, “The Big Breakup,” is from his book Load in Nine Times.

I know you are familiar with the term historical fiction, which refers to novels that are set in true historical situations and include real historical figures. Walker’s Load in Nine Times is historical poetry, based on his deep research into the pension records of the U.S. Colored Troops and into the lives of their families. Walker grew up in Danville, Kentucky, just sixteen miles down U.S. Highway 27 from Camp Nelson. He grew up knowing the story of the place. But not the whole story. A few years ago, he was invited to help create a project about the U.S. Colored Troops based on historical records that were being digitized for the first time.

Frank X. Walker: I was initially hired to write some biographies for an online humanities project that was committed to putting online all these sets of new data about African-American soldiers who fought in Kentucky, who were Kentuckians. And they had all this data, pension records, service records, medical records, and they were digitizing everything of And they knew that almost nobody knew all this historic information. And they asked me and about a dozen other writers to take a set of, you know, material and then kind of put together … these short biographies on individual soldiers, and they wanted to put them on the website.

And so I did about four or five of those and I kept being blown away by the quality of the material that I was reading. I mean, it was had such of they read like short little movies to me and I wanted to do more. And I asked permission to add some poems to the bios and they were like, hell yes, please. And so I, you know, I would turn in the bios and, and one or two poems, and I really enjoyed that process. I mean, every time I would harvest a new set of material, these poems would just seem to fall out.

Chuck Reece: Frank’s writing and research led him to uncover important facts about his own family’s history, specifically the stories of his ancestors Mary and Randall Edland, who fought in the 125th US Colored Infantry, and Elvira and Henry Clay Walker, who fought in the 12th U.S. Colored Troops Heavy Artillery.

Frank X. Walker: I recalled in that process that, you know, … there were a couple of ancestors on my family tree that we believed had connections to the Civil War, but we had never confirmed it. And, you know, since they had all this data and they were connected to the folks in Washington, D.C., and in the Smithsonian archives, and, you know, they had the resources. I just gave them a couple of names.

Chuck (from interview): Of people from your family.

Frank X. Walker: People from the family tree. And a week later, they emailed me a 99-page document for one of my ancestors, you know, Randall Edlund. I was blown away. And I knew as soon as I started reading about his life that I was going to write poems about it. … I really believed even then that there was a book worth of stories worth telling.

Chuck Reece: That book, Load in Nine Times, contains sixty-seven poems, in which Frank steps into the shoes of specific members of the Colored Troops and their families, and a few other people whose lives affected theirs. He tells their stories, drawing from actual records of their lives.

Chuck (from interview): You dedicated it to Mary and Randall Edland, a married couple. Your ancestors. And Randall fought in the 125th US Colored Infantry.

Frank X. Walker: Yes.

Chuck (from interview): And … Elvira and Henry Clay Walker. … And Mr. Walker fought in the 12th U.S. Colored Troops Heavy artillery.

Frank X. Walker: They did. And you know, we have of we're still trying to confirm … there’s a William Edlund who was also mustered in the exact same day, the exact same place in Lebanon, Kentucky. And served with Randall. And we're trying to figure out if that was his oldest son or his brother. We haven't been able to confirm that yet, but we have at least three, maybe four relatives. And there's both sides of the family tree that were part of the … over 10,000 soldiers, you know, at Camp Nelson in Nicholasville, Kentucky. One of the most undertold stories about the Civil War that I've ever, you know, been connected to.

I think that people, you know, here at Camp Nelson, they think, you know, okay, it's an army camp. But they don't know that it was a refugee site as well, that most of those soldiers, you know, 23,703 soldiers from Kentucky fought in in the Civil War. And most of them were stationed at Camp Nelson.

Chuck (from interview): You're talking about 23,000 African American soldiers.

Frank X. Walker: … which stuns people.

Chuck (from interview): And their families were refugees.

Frank X. Walker: Their families were stationed almost across the street in the refugee camp. They had a hospital and a school, barracks, you know, food and clothing available. … And it became the first really free space in Kentucky for African Americans … and that was never part of our history books.

Chuck Reece: Once again we encounter the swamp that is Southern history. But the beauty of Frank X Walker’s historical poetry is that it brings the stories of the U.S. Colored Troops at Camp Nelson not only out of the swamp and into the sunlight, but also into vivid color. In his poems, their stories become far larger than reference points in old documents. The people come fully to life.

Which makes readers, like me, feel their pain, their uncertainty, and their resolve at a level history books alone could never achieve. I think the best way to show you that——and to end this episode——is to let Frank perform his work. I asked him to read two poems that appear one after the other in his book.

The first is written in the voice of a slave owner, a woman named Matilda Burks. It’s called “After My Decease, a Last Will and Testament.” The second is written in the voice of Grace, a slave owned by Matilda Burks. Frank drew the story in these two poems from the records. Matilda Burks was a real person.

Frank X. Walker: Matilda Burks was a slave owner. Lived near Louisville, Kentucky. … Her name was on the documents that we were able to unearth that had been digitized, that included … the slave census that registered all 48 of her slaves. We found her actual will. … Where she redistributed her slaves to her own children. And Grace, you know, obviously, is the mother of those children that were redistributed. … But who didn't have a voice. And it was important to me after I had written this poem that that tried to, you know, raise to the surface, you know, just how easy it was to consider people property and redistribute them. … I want people to know what it might have felt like for the mother of those children to, like, witness it. And then if she had something to say, imagine what she would say.

Chuck Reece: We’ll leave you to listen to these two poems.

Frank X. Walker:

“After My Decease: a Last Will and Testament”

[It's in the voice of Matilda Burks.]

I give and bequeath all my silverware and plate

of every description, also my beds, bedsteads,

bed clothes, and remaining household and kitchen furniture

to be split equally

amongst my daughter and 3 sons.

I give and bequeath to my daughter Nancy

my fortepiano

and also my Negro woman Grace

and her youngest daughter Harriet.

I give to my son John

all my pictures

and also my negro boy Alfred,

son of the above mentioned Grace.

I give to my son James

my negro girl Sally

daughter of the above mentioned Grace.

And to Charles, I give my Negro boy Wesley.

Should the said Grace or any of her increase

or any of the 48 slaves of mine

which shall become the property

of any of my children

prove troublesome and unmanageable

then it is my wish that such slave or slave

so offending shall be sold

and the proceeds of such sale or sales

be appropriated to the purchase

of other servants or servants

to supply the place or places of those sold.

In witness where of I have hereunto set my hand

and affixed my seal this seventh day of December

in the year of our Lord 1857

Signed, sealed and acknowledged

—MATILDA BURKS

“Mother to Mother”

I believes you believes

this ink and paper testament

show off your love for your children

and how generous you can be.

And that may be so.

But it easy to be generous

when you gone.

What use a dead body got

with silver and slaves?

While I thank you

for the giving over a my Harriet

with me, I feel no such kindness for

the plowing up of the rest a my children.

And the added threat of being sold away

for daring to say anythingbut yes ma’am and yassa boss

have me dreaming a swinging

the back a my hand

and fixing my own seal.

You can bind all my increase.

you can sell South my ungrateful tongue,

but you can't never give away my dreams.

—THE ABOVE MENTIONED GRACE

CONCLUSION

Chuck Reece: I’d first like to thank Frank X Walker for being incredibly generous with his time——and for how his poetry inspired me to learn more about the history that inspired him. I’d also like to thank Steve Phan of the National Park Service, Dr. Holly Pinheiro of Furman University, and Dr. Edda Fields-Black of Carnegie-Mellon University for teaching me well about the history of the U.S. Colored Troops, Camp Nelson, and Harriet Tubman.

When we spoke to Edda for this episode and talked about her book Combee, neither she nor I had any clue her` book would soon win the Pulitzer Prize for History. So besides giving Edda my thanks, I want to add…congratulations! That’s awesome!

You’ve been listening to Salvation South Deluxe, proudly produced in cooperation with Georgia Public Broadcasting and its network of twenty radio stations around our state. Every Friday, we add a new three-minute commentary about Southern stuff to our podcast feed, and every month or so, we add longer, dee-luxe stories, such as the one we’ve just told you.

I’m Chuck Reece, your host and the editor-in-chief of Salvation South, which you can find twenty-four-seven at SalvationSouth.com. On there, we have the Alabama poet and professor Jacqueline Allen Trimble’s in-depth interview with Frank X Walker about his book Load in Nine Times.

Our producer is Jake Cook. I thank him for his hard work and his great willingness to swim the swamps of Southern history with me. GPB’s director of podcasts is Jeremy Powell, and none of this could have happened without the help of GPB’s Sandy Malcolm, Adam Woodlief, and Bert Wesley Huffman.

We’ll be back next month with another full-length episode of the Salvation South Podcast.

---

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. Salvation South Deluxe is a series of longer Salvation South episodes which tell deeper stories of the Southern experience through the unique voices that live it. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South and wherever you get your podcasts.

Nearly 200,000 Black soldiers fought for their freedom in the Civil War. And their families risked everything alongside them. Host Chuck Reece explores the legacy of these soldiers through the powerful, historical poetry of Frank X Walker, and with the help of Pulitzer Prize-winner Edda Fields-Black, historian Holly Pinheiro Jr. and Steve Phan, Park Ranger at the Camp Nelson National Monument. This episode brings to light the struggle, resilience, and enduring impact of African American soldiers in Southern history.