Section Branding

Header Content

Keys To Leo Frank's Prison Cell Discovered By UNG Student

Primary Content

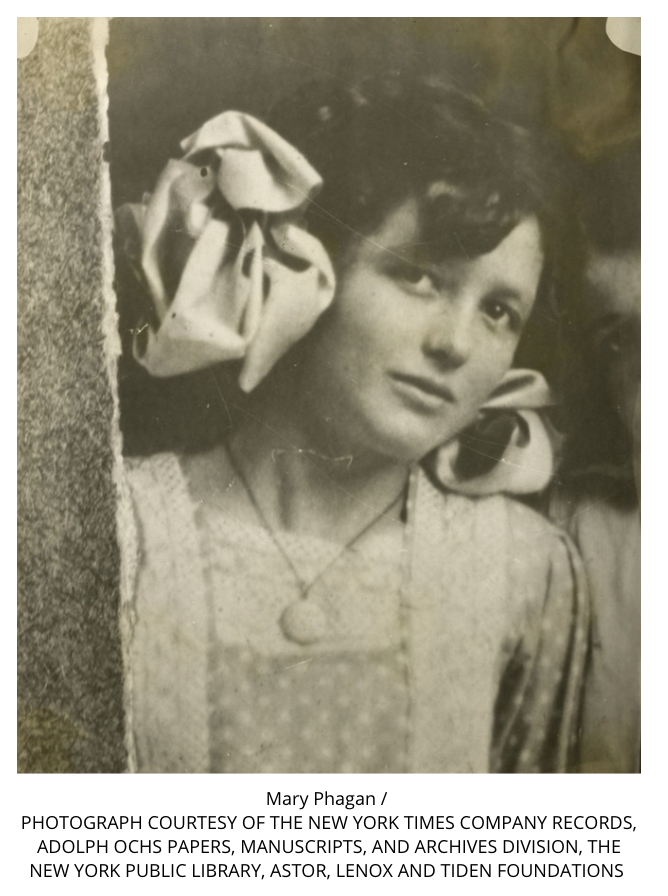

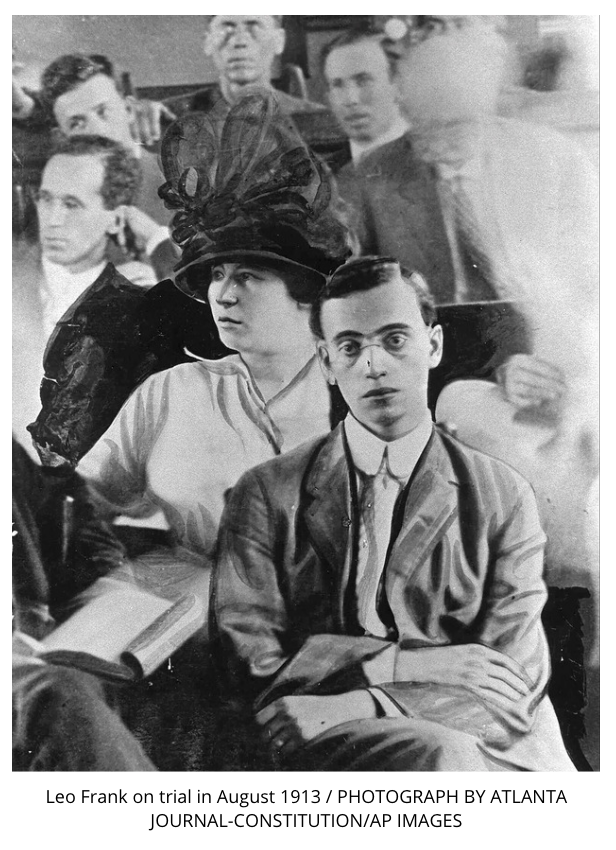

In 1913, a sequence of disturbing crimes occurred in the Atlanta area, beginning with the shocking murder of Mary Phagan, a 13-year-old employee at the National Pencil Factory who was found strangled in the basement of her workplace. The factory's Jewish superintendent, Leo Frank, was convicted of her murder and subjected to vigilante justice when he was kidnapped from prison and lynched in 1915. His lynching drew national attention and became the focus of social concerns, especially regarding antisemitism.

The case around Leo Frank embodied the area’s growing tensions and fears brought about by the New South’s urbanization, industrialization, and changing economy. Many Southern white families resented Northern industrialists like Frank, whom they blamed for the destruction of traditional family values as women and children entered the workforce. At the turn of the century, antisemetic views were also on the rise as an influx of Jewish people from eastern and southern Europe immigrated to the South. Southern newspapers at times sensationalized stories that inflamed these local prejudices and bigotry.

This was the backdrop against which the murder trial of Leo Frank, a well-educated, Northern industrialist Jew, took place in 1913.

Despite the lack of any credible evidence against Leo Frank, he was quickly fingered as Mary Phagan’s killer. Less than four months after her body was discovered in the factory, Frank was tried and convicted of the murder. He was sentenced to death by hanging.

Following a series of failed appeals, the case made its way to the United States Supreme Court, as Frank’s lawyers argued that he did not receive a fair trial. His appeal was denied in April 1915. His sentence, however, was commuted to life in prison by then-Georgia governor John M. Slaton, who considered arguments from both sides as well as new evidence. The public was outraged by the governor's decision.

A fellow inmate attacked Leo Frank soon after he was transferred to the prison farm at Milledgeville. On the night of August 17, as he recovered in the infirmary, an armed lynch mob from Marietta stormed the state prison, ordered Warden J. E. Smith to unlock the infirmary, and abducted Frank. He was hanged from an oak tree at Frey’s Gin in Marietta at 7:05 am the following morning. Within the hour, nearly 1,000 people had gathered at the site, including mothers with their children.

Over 100 years later, the conviction and subsequent lynching of Frank, the only Jewish person ever lynched in America, continues to be at the forefront of conversations regarding racial prejudice and social justice. The continuance of these conversations is in part thanks to the state’s Georgia Studies curriculum, which requires every eighth grade student to “examine antisemitism and the resistance to racial equality exemplified in the Leo Frank case” during the New South era.

Many university professors also cover the case when discussing social justice, race relations, and sensationalism in the media, among other topics. One such professor, Dr. Lauren Yarnell Bradshaw, who is an assistant professor of teacher education at the University of North Georgia, promotes inquiry in her Social Studies Methods class by inviting her students to analyze artifacts from the Leo Frank case.

“The thing that I want my students to understand is that we don’t want to replace one single narrative with another single narrative,” said Dr. Bradshaw. “You need to train them how to analyze their own artifacts and how to incorporate them into their understanding of history.”

While Dr. Bradshaw typically provides artifacts from the Frank case or directs her students where to find them, one student this past semester produced an artifact that neither Dr. Bradshaw nor any expert on Leo Frank had ever seen before: Warden J. E. Smith’s keys from the Milledgeville State Prison. These were the same keys that the lynch mob used to unlock the prison’s infirmary door before seizing Leo Frank.

“From a historian’s perspective and as a Georgia resident, I can tell you I think the discovery of these keys is outstanding and really exciting,” said Dr. Bradshaw. “This case is just as significant today, in my mind, as it was 107 years ago.”

Brittany Rhodes, a graduate student at UNG, discovered the keys in 2002 while she and her mother Stephanie were cleaning out Warden Smith’s estate in Decatur. The keys and their history would likely have been thrown out if it weren’t for Stephanie’s love of old keys.

“Up until this point, I had kept them in a drawer at home,” said Stephanie.

“It was two or three years ago that together we started really researching the keys and the warden’s name which was on the [key] ring,” said Brittany. “After learning about the Leo Frank case, and since Smith was the warden at the time and the keys are dated for 1915, we figured these were most likely the keys used to abduct him from prison.”

When Brittany showed Dr. Bradshaw the keys in late 2019, they discussed ways to share them with the public and contacted the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum in Atlanta.

Jeremy Katz, the Director of the Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History at the Breman Museum, says the keys have been authenticated and will be further examined by Leo Frank experts.

The Breman Museum is home to the most extensive collection of Leo Frank artifacts in the world. One of its past exhibitions, “Seeking Justice: The Leo Frank Case Revisited,” provided an immersive experience for visitors as they were invited to examine the tragic events of 1913 to 1915.

“This story of Leo Frank needs to be constantly told over and over until people understand how misinformation and yellow journalism can lead to people dying,” said Katz. “And the Frank case is a perfect example of that.”

The Rhodes family agreed to leave the keys on loan with the museum for the next five years. They were immediately catalogued in the Breman’s online database and displayed in the museum’s recent acquisitions case.

“They are now being stored in our climate controlled archives and galleries so they will be well taken care of and made accessible to the public,” said Katz. “They’re going to get a lot of attention.”

Archives of the Leo Frank case can be viewed in the Breman Museum’s online collection catalogue.

For more information about this case, watch the Georgia Stories episode, "The Sensational Case of Leo Frank."

Secondary Content

Bottom Content