Section Branding

Header Content

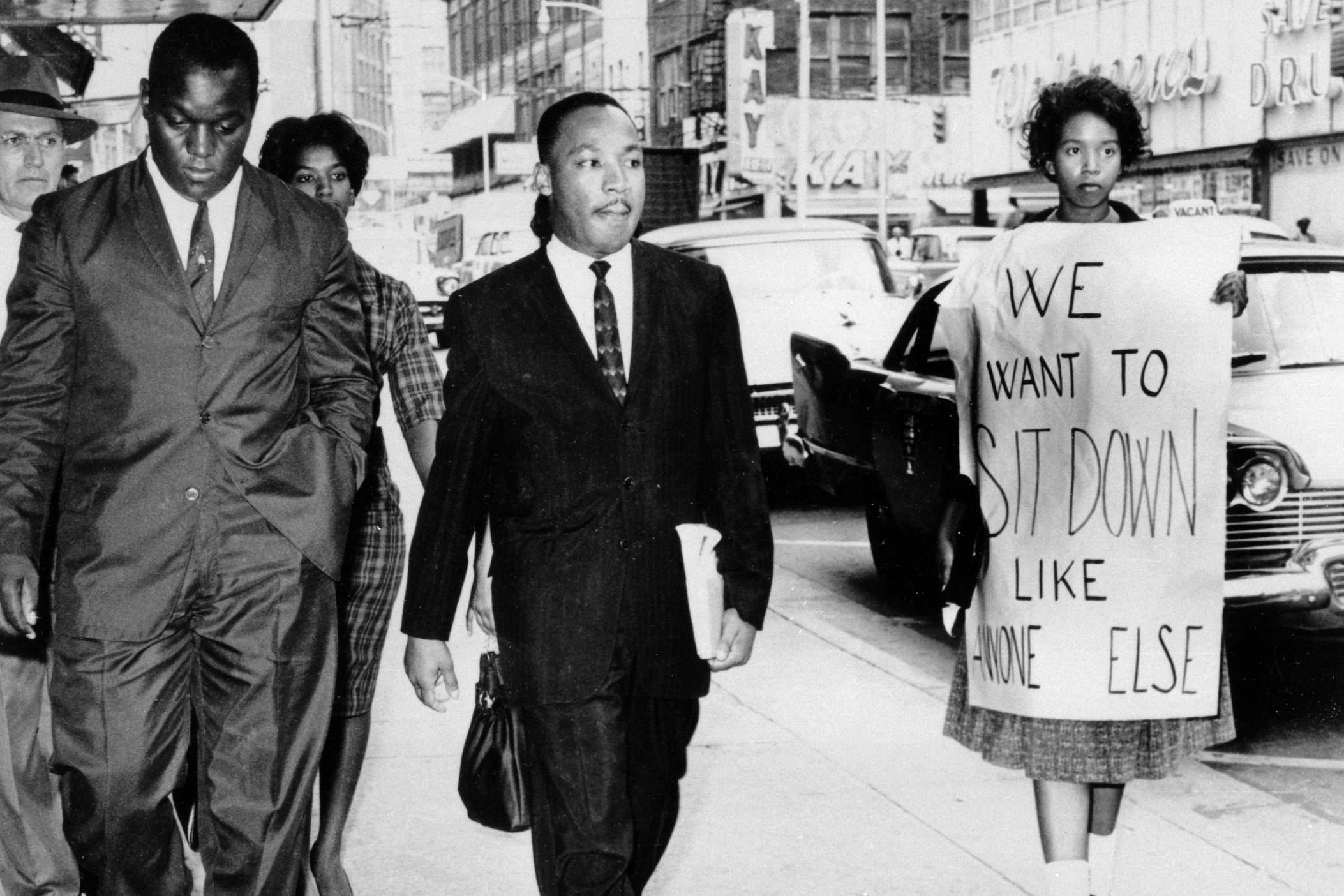

Georgia Today: How MLK's Prison Sentence Landed JFK In The White House

Primary Content

Weeks before the 1960 presidential election, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested for participating in a lunch counter sit-in in Atlanta and sentenced to four months of hard labor. Thanks to some back-channel moves by the Kennedy campaign, King was released from prison. On Georgia Today, author Paul Kendrick explains how that changed party allegiances for Black and white voters in the South for generations.

RELATED: 'How Martin Luther King Jr.’s Imprisonment Changed American Politics Forever'

TRANSCRIPT:

Virginia Prescott: It's Georgia Today. I'm Virginia Prescott, in for Steve Fennessy. As the nation celebrates Black History Month, we're taking you back to an often-overlooked chapter in Georgia's civil rights history. Before the Selma to Montgomery march, before the “I Have a Dream” speech, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was sentenced to four months of hard labor for an outstanding traffic violation. It's October 1960, just weeks before Election Day. Dr. King is arrested for taking part in a lunch counter sit-in at Rich's department store in Atlanta. He was then transferred to DeKalb County, sentenced, jailed and then taken in the dead of night to a Georgia state prison. Thanks to some back-channel, even rogue moves by the Kennedy campaign, Dr. King was released.

Martin Luther King Jr.: I owe a great debt of gratitude to Sen. Kennedy and his family for this. I don't know the details of it, but naturally, I'm very happy to know of Sen. Kennedy's concern.

Virginia Prescott: Black voters took note and gave Kennedy a decisive edge over Richard Nixon in the closest presidential election of the 20th century.

Genesis Reddicks: That actually changed the entire tide of the civil rights movement and the political aspect of the country as well.

Virginia Prescott: Genesis Reddicks is a senior at Decatur High School in DeKalb County. She spoke before the Decatur City Commission last summer to advocate for a marker in Decatur's town square to memorialize King's arrest and trial.

Genesis Reddicks: We are working on a campaign to erect a marker which will recognize the events of when Martin Luther King was actually sentenced to a chain gang in Decatur City right across the street from City Hall.

Patty Garrett: This is the resolution supporting application to the Georgia Historical Society for a historical marker commemorating Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Virginia Prescott: That's Decatur Mayor Patty Garrett.

Patty Garrett: And whereas the Commemorating King team has researched and documented the events surrounding a traffic citation issued to Dr. King in DeKalb County and his subsequent detention and sentencing to prison and hard labor…

Virginia Prescott: That detention changed King's life and American history. A new book digs into just how. My guest, Paul Kendrick, is coauthor with his father, Stephen, of Nine Day:s The Race to Save Martin Luther King Jr.’s Life and Win the 1960 Election.

Virginia Prescott: So, Paul, this is not something we often see in the highlight reel of Dr. King's life. What happened?

Paul Kendrick: So he had moved home to Atlanta in 1960 after the Montgomery bus boycott and a few years on from the Montgomery bus boycott, as he was really struggling to figure out how he was going to make national change, how he would move America towards equality and — and civil rights victories as he had the small Southern city. And he's drawn into the student sit-ins that were happening because these were his friends.

Reporter: It was announced just the other day that variety stores in 112 Southern cities would voluntarily integrate their lunch counters and cafeterias. I take it you do not feel this is sufficient progress?

Martin Luther King Jr.: It represents real progress, but it certainly isn't enough.

Paul Kendrick: King and the students, their primary focus was getting downtown Atlanta — Rich’s and the downtown department stores — to desegregate. The focus was on Atlanta. They were Atlantans. And so, here's Dr. King talking about that.

Martin Luther King Jr.: I'm sure that with the reasonable climate in Atlanta, it is possible to desegregate lunch counters without any real difficulty. And the transition would be a very smooth one.

Paul Kendrick: He did a sit-in at Rich's and went to Fulton County Jail, along with the black Atlanta college students that were forcing the issue of civil rights three weeks before the 1960 election. But he had had a previous traffic violation, suspended sentence from DeKalb County. And that judge, Judge Oscar Mitchell, was able to get him back into his Decatur courtroom and sentence him to four months hard labor.

Virginia Prescott: Assume DeKalb County and Decatur at this time were KKK strongholds, mostly. Judge Oscar Mitchell was presiding over this case. What went on in that courtroom?

Paul Kendrick: King had a great Atlantan hero and — and, really, an American hero as well: Donald Hollowell.

Donald Hollowell: You have asked me, what other plans do we have in connection with Rev. Martin Luther King's release?

Paul Kendrick: Hollowell had driven the back roads of Georgia, defending Black men falsely accused of different things. He had risked his life in the years before he became the student sit-in — Atlanta college students’ lawyer, as someone who they could always call on who would be there to defend them. And Hollowell, in this hearing in Decatur, he's asking the Rich’s staff, well, was there anything different about these students than anyone? They were nicely dressed, right? They were not fighting. They were not creating noise and — and — and really making, showing everyone the absurdity of these segregation rules that King and the students who went to Rich's department store’s Magnolia Room, in order to, you know, have tea, have lunch like everyone else but were arrested for that to really show the unfairness of it.

Donald Hollowell: If the court fails to release them, of course, we would take other steps to appeal or to effect a release of Rev. King.

Paul Kendrick: Now, Judge Mitchell wants to talk about motor vehicle codes. You know, he wanted to use the law, use the technicality in order to persecute King because, as Hollowell is saying, no one's ever been sent into state prison for four months for having an out-of-state license a few months after they moved here to Georgia. So Mitchell wants to focus on that and Hollowell wants to expose what's going on to the nation. But Mitchell doesn't want to hear it and does, to the shock of the courtroom, sentences King to four months in state prison that day in Decatur.

Charles Black: I was at that hearing and the judge sat sideways of the bench while the defense was presenting their case. He wasn’t interested in anything they said. He had a comic book, as a matter of fact, thumbing through this comic book.

Paul Kendrick: Charles Black was a leader in the Atlanta student movement, famously brave for all the sit-ins he did. And he's been really a mentor now to these young activists in Decatur. And here's a recording they did with him as he talked about watching his friend Dr. King sentenced.

Charles Black: So when he violated his parole, he was immediately sent in the dead of night to Reidsville Prison in the back of a paddy wagon with a loose German shepherd dog in there. And King has said — was recorded as saying later that that was the most afraid he’d ever been.

Donald Hollowell: We prepared a writ of habeas corpus, which we plan to submit this morning at eight o'clock. However, when we called at 8:00 for the purpose of ascertaining the whereabouts of the sheriff for making service, we were informed that Rev. King had been taken down to Reidsville at 4:05 this morning.

Paul Kendrick: King thought he was being lynched. He thought he was never going to get to see his family ever again. These things happened in the American South at that time where these kinds of nighttime killings could happen and sadly, tragically happened quietly and explanations never being given. So he's — he's put in the back of this car. He's driven away from Decatur. No explanation given for where he's going. And — and it goes for — for hours.

So as light is rising, he realizes, OK, he's at Reidsville State Prison. The anxiety of that moment is unfathomable. But it was transformative for King. And he did draw strength from that experience that would allow him to face down the things that he needed for national change, for his activism to be effective in moving the American soul and getting these politicians to the public will behind them to — to support the Civil Rights Act. And so that's — that's what he went through on that drive from Decatur to Reidsville.

Virginia Prescott: The nation certainly is captivated, there are — there are op-eds being written in major newspapers, telegrams to Mayor Hartsfield of — of Atlanta, although it's out of his hands.

William Hartsfield: ... and the existence or complications caused by an outside traffic case have nothing to do with this matter. We hope it is settled in a friendly way, however.

Virginia Prescott: The whole nation is watching and the South looks really bad, so we — so what was at stake for the Nixon and Kennedy campaigns at this time? What kind of calculation would it be for them to help a civil rights leader in the South?

Paul Kendrick: It looked like Black vote might go about 50-50. Nixon was seen as sympathetic to civil rights. And so Kennedy has to hold on to these states. But he has a team on his campaign, a civil rights trio. Louis Martin, Harris Wofford, Sargent Shriver really believed that Black voters could be the difference for Kennedy in, you know, what looked like and was, I mean, as close of an election as we've ever had.

Newscast: Your candidates for the most important office in the free world seek your concern, your thoughtful judgment and your votes in this vital campaign of 1960.

Paul Kendrick: King was a friend of Harris Wofford, a white Howard Law graduate who was obsessed with nonviolence and then and befriended this minister who was who was doing it in the South and was an adviser to King, but also worked on the Kennedy campaign. So — so his friend is in jail. So Harris Wofford calls down to Morris Abrams, a Jewish lawyer working with the King family, and said, well, what's going on here? You know, can — can Mayor Hartsfield get him out? And — but Mayor Hartsfield, who is such a colorful Southern character, he goes out to the press and said, well, John Kennedy has indicated his interest in this case.

William Hartsfield: I would not want to say who I talked with in the Kennedy headquarters, but I did talk with them and they transmitted to me the friendly interest of Sen. Kennedy in a friendly solution of this matter, coupled with the statement that neither they nor Sen. Kennedy had any desire to be put in the position of interfering.

Paul Kendrick: And so suddenly their campaign is publicly associated with this, which is making the — the higher-ups in the Kennedy campaign, is making Bobby Kennedy very nervous. But now they are engaged.

John Kennedy, he didn't just want gestures, he wanted to actually solve the problem, and so he kind of out — outdoes the mavericks by calling Georgia's Democratic governor, Ernest Vandiver, who when King moved home, Vandiver said, “Well, violence follows wherever Martin Luther King comes.” He was using this playbook of fear and scapegoating about Martin Luther King, completely hostile to civil rights, was trying to hold on to all-white schools, segregated schools at the time. And so, no friend of Martin Luther King, that's for sure.

But he is a Democrat. And so John Kennedy is saying, “Hey, this is bad for our party. We got to get Martin Luther King out,” because Kennedy doesn't have to say it was a Democratic judge, Oscar Mitchell, that sentenced him. And so this whole thing is a mess. So they start working behind the scenes: Kennedy calling Vandiver, Vandiver calling up a friend of Mitchell — a guy named George Duart — and they start working on the judge and come up with kind of what's going to be a cover story where Bobby Kennedy is going to need to call the judge.

Now that's gone down in history as Bobby just got so mad that he just flat-out called and he did get eventually mad about this case. But there were these back channels that kind of set it up. And so it reads like a thriller because there are these twists and turns in the story between the Georgia Democrats and the Kennedy campaign.

But it's just a fascinating story about politics, where you have someone like George Duart, who is a white supremacist, literally a white supremacist leader in Georgia, and he's not helping get Martin Luther King out because he finds King sympathetic. It’s because he wants — if the Democrats win the White House, they think, OK, well, they'll owe us a favor. They'll keep civil rights enforcement out of Georgia. We just got to solve this and get our friends in the White House. But, of course, there were changes coming to both of our political parties out of this that were not what those Georgia Democrats wanted.

Virginia Prescott: Just ahead: Black voters delivered for Kennedy; did he come through for them? This is Georgia Today.

[BREAK]

Virginia Prescott: It's Georgia Today; I'm Virginia Prescott. We're looking back at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s 1960 arrest, which will be memorialized this year in a marker in downtown Decatur. After participating in a sit-in, King was sentenced to a chain gang for a probation violation. It was the October surprise of that year's presidential race. Back-channel interventions by John and Bobby Kennedy and the Kennedy campaign helped secure King's release, which political scientists point to as critical for JFK's a narrow win over Richard Nixon. That victory helped change party allegiances for Black and white voters in the South for generations. Here's Dr. King speaking moments after his release from Reidsville prison.

Martin Luther King Jr.: Well, a great debt of gratitude to Sen. Kennedy and his family for this. I don't know the details of it, but naturally, I'm very happy to know of Sen. Kennedy's concern and all that he did to make this possible. I might say that there are no political implications here. I'm sure that the senator did it because of his real concern and his humanitarian bent. And I will always say that I'm deeply indebted to him for it.

Virginia Prescott: A new book digs into the tense days following Dr. King's arrest. I'm talking with Paul Kendrick, coauthor of Nine Days: The Race to Save Martin Luther King Jr.'s Life and Win the 1960 Election. Paul, let's pick up that story, after Dr. King walks through those gates at Reidsville State Prison.

Paul Kendrick: They rented a little plane to go out there, bring him back as fast as possible. And they had a big rally at Ebenezer that night. And Daddy King says, and I'm paraphrasing, but if he, John Kennedy, could wipe the tears from my daughter-in-law's eyes, then he can be my president. And that's a very powerful statement for this former Republican to be wholeheartedly, emotionally endorsing John Kennedy. That's a big deal for the shift in Black voters that is going to be happening from the Republican to the Democratic Party.

Virginia Prescott: This was the closest election of the 20th century, and this is just 11 days after after Dr. King got out of Reidsville State Prison. So this — this surge in Black votes, how how closely can you tie it to the events of what happened?

Paul Kendrick: Yeah, so polls are pretty primitive at this point. But we do think that in nine states, Black voters were the difference.

Newscast: The unexpectedly delayed climax saw Sen. Kennedy the victor, with a clear margin of electoral votes. At 44 years of age, he is the youngest man ever voted into the White House and the first Catholic chief executive in the history of the nation. With victories in the southern Bible Belt as well as the industrial centers of the North to attest the shattering of a long...

Virginia Prescott: Do you think this event brought an about-face in the care and concern and — and priority of civil rights in the Kennedy administration?

Paul Kendrick: That was what King was looking for from Kennedy. He wanted to see a more visceral connection to the issues they face, not see it as a kind of analytical problem. But yeah, but the Kennedys had not taken the time to focus in on civil rights inequalities in America. You know, coming from their privileged background, they just had not put themselves out there to expose themselves to the realities of — of what other Americans were dealing with. But this was an important moment for them. But it was not it was not the whole story because there were more things that King had to push them on to get action.

Martin Luther King Jr.: President Kennedy has done some significant things in civil rights. But at the same time, I must say that President Kennedy hasn't done enough and we must remind him that we elected him.

Paul Kendrick: It wasn't just that Kennedy won and then he got to the White House, said, all right, I'm going to pass civil rights legislation. That had to be a few years of brave protest of King's activism, the civil rights movement, the women and men who bravely put their bodies on the line in places like Birmingham that would eventually get Kennedy to act on behalf of America, but in particular of voters who had really put their trust in him as the person to advance it.

John F. Kennedy: Next week, I shall ask the Congress of the United States to act, to make a commitment it has not only made in this century, to the proposition that race has no place in American life or law.

Paul Kendrick: And then it would be Johnson that — they got this legislation over the line after Kennedy's assassination, but this trio was pushing every step of the way —Louis Martin, Harris Wofford, Sargent Shriver — of really trying to make the promise of that campaign realized in policy. And that wasn't easy. But it takes pushing to make sure the politicians really deliver. And that's the lesson, I think, for all of us that's relevant today.

Virginia Prescott: Well, if we take the long view now, we have, just recently, the minister of the Ebenezer Baptist Church — the very church where Daddy King and where Martin Luther King, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. both preached — now that minister, Raphael Warnock, is in the Senate.

Raphael Warnock: Whether you voted for me or not, know this: I hear you. I see you. And every day I'm in the United States Senate, I will fight for you.

Virginia Prescott: This gives you an arc of history, where things have come. Well, how do you see it?

Paul Kendrick: It's fascinating that the playbook that was used against Rev. Warnock was really all about scaring people about him. And it made me think back to everything I read in these Georgia papers in 1960 when King had moved home. And Gov. Vandiver is really trying to spread fear about him and say that he — he’ll cause violence. Violence will come if, you know, with King Jr. moving home to Georgia. And so, you know, obviously it's sad that those kinds of appeals are still used.

But it is obviously an amazing turn of events for DeKalb, the county that sentenced King to this four months to this place that was so feared by Black Atlantans, to be the place that the nation watches as those votes really come in for Ebenezer’s minister, Rev. Warnock, is really — and when you look at the power of organizing, when we talk about young people, the ones that have gotten this marker to — to King approved and all the voter registration and the things that have happened. But you think about the activism of 1960 and so how organizing, how forcing change, how — how just getting involved and standing up can really bring about such historic things as now we have, you know, the direction of the country is really set by Georgia.

And so there are these — these echoes that are with us that that are that are hopeful that we can build on and let's make progress together that helps all of our families. Let's — let — let's support civil rights progress. It’s certainly something that that we can hope to — to — to build on as a country.

Virginia Prescott: My thanks to Paul Kendrick, coauthor with Stephen Kendrick of the book Nine Days: The Race to Save Martin Luther King Jr.'s Life and Win the 1960 Election. As we told you earlier, there are plans to place a marker in downtown Decatur where King was sentenced. That's thanks to Decatur High School student Genesis Reddicks and other student activists. She was among protesters who successfully pushed last summer for the removal of a Confederate monument in Decatur Square.

Genesis Reddicks: I think the significance of seeing a marker coming up and then also a racist monument going down kind of is just so significant to our times. I'm hoping that this will show up in history books or be a lesson taught, at least in the Decatur community.

Virginia Prescott: Reddicks says it's an important step to confronting racism in this country.

Genesis Reddicks: We have a long way to go.

Virginia Prescott: She says plans are in place for the marker to go up this spring, I'm Virginia Prescott, in for Steve Fennessy. This is Georgia Today, a production of Georgia Public Broadcasting. Our producer is Sean Powers. You can subscribe to our show anywhere you get your podcasts. And please leave us a rating and review on Apple. Thanks so much for listening. We'll be back next week.

Transcript by Khari J. Sampson