Section Branding

Header Content

Georgia Certifies First STEM School

Primary Content

Every morning, the roughly 270 third, fourth and fifth-graders at the Marietta Center for Advanced Academics (MCAA) each spend about an hour doing activities like these:

In one class, Nino Fasula is working on an assignment that combines science research and creative writing.

“We started off learning about poems, and then we started learning about Mars,” he says. “So we just started to combine Mars and poems, so we came out with starting to make Mars poems.”

Down the hall, Nyah Gulri is designing a birdhouse. ”I’m looking at birds that are in Georgia that nest in birdhouses,” she explains. “I found a bird called a brown thrasher and I’m looking at how big of a nest they need.”

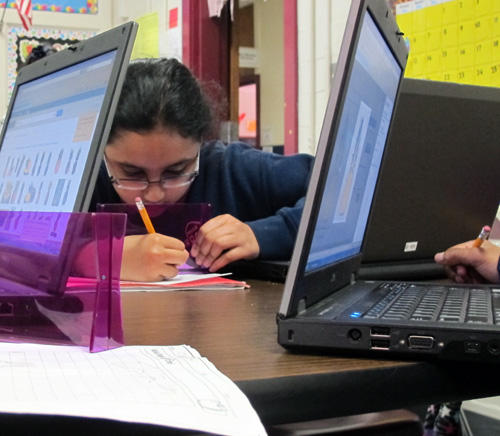

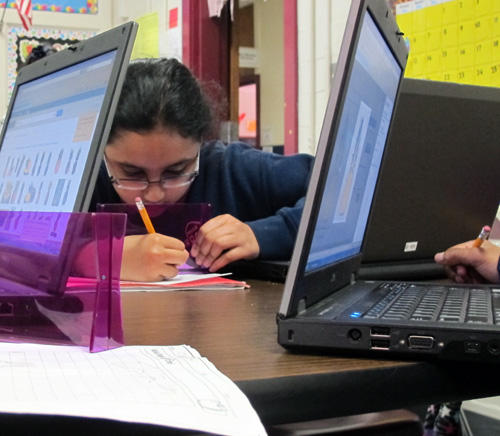

And Shreya Gelli is drawing to-scale blueprints of a sculpture that she will eventually build out of plywood and recycled bottle-caps.

“We’re doing a pineapple,” she says. “First, we find out on the internet…how tall it is. Then we go onto a website that converts it to centimeters, and that’s the dimensions we’re going to use when we do it on the plywood.”

What all these classes have in common, says MCAA principal Jennifer Hernandez, is that students use science, math and technology to solve problems rooted in engineering and design.

“We don’t want them to create something that’s cookie-cutter; we don’t want to tell them what to do,” Hernandez says. “So they are given the engineering design challenge – the problem – they’re given the criteria and the constraints and then they have to develop what they want the end product to be. And that’s where the innovation and the creative and critical thinking come in.”

It’s that way of designing a class that helped MCAA become the state’s first school to win STEM certification from the Georgia Department of Education. State officials hope that the new designation will help parents find top-notch science, technology, engineering and math programs and give schools the incentive to bring their programs to a higher level.

President Barack Obama has made improving STEM education a national priority, and many states are trying to spur schools to bolster their programs. Georgia’s STEM certification program is one way of doing that.

Gilda Lyon, who directs the state’s STEM certification program, says that even schools with strong math and science programs might not meet the qualifications for certification.

“A lot of schools are doing real high-level math and science, but they don’t have any business partners or they don’t give the teachers time to plan together or the math and science is simply isolated,” Lyon says.

What she’s looking for is schools that show how the fields relate to one another.

“So that students understand that math is not just for math class – how many times have we heard kids say, this is not English, why do I need to learn English here?” Lyon says. “We want them to understand that math is a part of science and math is a tool for science teachers to help students become deeper learners.”

Kara Householder, the fourth-grade teacher overseeing Shreya Gelli’s pineapple sculpture project, explains how that integration works in practice. “What this class does is we combine art and mathematics with the engineering process,” she says.

Householder teaches her students about renewable and non-renewable resources by having the students collect plastic bottle-caps – which she says would otherwise probably end up in landfills or waterways. Instead, the students use the bottle-caps to design and build sculptures.

“So we’ve found a way to reuse them and a way to create some beautiful artwork,” Householder says. “So they study scale factor, blueprint design, symmetry, drawing to scale, which they’re working on now. And they’re finding it extremely difficult to make their blueprints symmetric and at the appropriate scale.”

Linda Hutchinson, an MCAA teacher who helped develop the program, says that STEM fields are a natural for elementary school students because they bring skills from all academic fields together.

“It is all inclusive,” Hutchinson says. “We’re just bringing science out of the textbook and out of the science classroom and into all of the other areas of education.”

The school’s staff designed its own program so that teachers could tailor their classes to their own interests and passion, but also for a practical reason: most STEM material that had been developed was targeted for high school teachers. “Really, when we opened in 2005, you could have gone on the internet and looked up STEM elementary program and you wouldn’t have found anything,” Hernandez says.

“We tried to picture, what would this look like for elementary school students and for elementary teachers,” Hutchinson says. “It actually was not that difficult to do for an elementary school. Elementary tends to be a little more interdisciplinary anyway — we’re used to relating and making connections between our subjects a little bit more than the departmentalized atmosphere of middle school and upper school.”

The key piece, Hutchinson says, is the engineering. “That’s the part that scares most people but actually it’s the part that pulls everything together,” she says. “It’s the part that brings out the hands-on, problem-solving, real-world learning for the students. Engineering is designing to solve a problem.”

Lyon says MCAA is leading a trend of in-depth STEM instruction into the lower grades. ”They’re at the front wave of it, but I’m telling you, the wave right behind them is way up there,” she says. “I’m inundated every day with elementary schools wanting to know more about STEM.”

Francis Eberley, the executive director of the National Science Teachers Association, says that the trend is a big change from the past decade, when many schools reduced science instruction in order to spend more time focusing on more heavily tested subjects.

“What the science, technology and math schools are doing is that they’re really elevating science to the same level of importance as reading and mathematics, and that hasn’t occurred on a broad level,” Eberley says. “And I think Georgia is really doing that with this model.”

And while MCAA teaches students who already score high on standardized tests, school staff and Gilda Lyon at the Department of Education argue that it’s a model that can be used by any school.

“We want to make sure this is clear: This is not just for elite students, this is for all kids,” Lyon says. “The thinking processes that need to go on in STEM classes – those are the things that are good for all children, regardless of whether you ever go into a math field or a science field. The kind of wiring that goes on in your brain – that’s what’s important, that will not change in a child’s brain once that wiring for science and math takes place.”

As more schools prepare their STEM programs for certification, that theory is about to be put into practice.