Caption

The Folkston ICE Processing Center and the D. Ray James Correctional Facility in Folkston, on July 2, 2025.

Credit: Justin Taylor/The Current GA/CatchLight Local

The Folkston ICE Processing Center and the D. Ray James Correctional Facility in Folkston, on July 2, 2025.

Caitlin Philippo, The Current

Hunger strikers held in solitary confinement. Catholic and Muslim detainees denied access to chaplains. Medical staff acted “beyond safe limits” and contributed to the death of an Indian national.

These are among a long list of violations uncovered by federal inspectors at the Folkston immigrant detention center operated by The GEO Group since 2017 under a contract between the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency (ICE) and Charlton County.

The Folkston city limit sign near the The Folkston ICE Processing Center and the D. Ray James Correctional Facility in Folkston, on July 2, 2025.

Yet rather than levy meaningful fines or penalties in response to the infractions, ICE last month awarded the Boca Raton-based company a new, $47 million contract to consolidate the installation — formally known as the Folkston ICE Processing Center — with the D. Ray James Correctional Facility. The result will be a nearly 3,000-bed complex, making it the largest immigrant detention center in the U.S.

An examination of federal contracts and inspection reports with The GEO Group and obtained by The Current show staff routinely ignored federal safety and prison standards and kept detainees at the center, located 50 miles southeast of Brunswick, in unsanitary and dangerous conditions that threatened their health.

The substandard operations proved fatal for Jaspal Singh, who spent nine months at Folkston after entering the country illegally. In April 2024, the 57-year-old Singh suffered chest pain and eventually died when a doctor delayed treatment. The facility’s medical care “deviated beyond safe limits and directly contributed to his death,” according to the review of his death conducted by ICE.

Meredyth Yoon, the litigation director at Asian Americans Advancing Justice, an advocacy group that represents Folkston detainees, described Singh’s death as completely preventable and an illustration of systemic breaches by The GEO Group of its contractual obligation to operate according to ICE’s own standards for detention centers.

The GEO Group, which reported $2.4 billion in revenue in 2024, responded to requests for details about its health and safety guidelines with a statement that said it was in “strict compliance with ICE detention standards.”

The D. Ray James Correctional Facility in Folkston, on July 2, 2025.

How Folkston and other immigrant detention centers operate is more crucial than ever. The tax-and-spending bill passed by U.S. Congress and signed into law by President Trump earlier this month provides for more than $75 billion in supplemental funding over four years for ICE to expand interior enforcement operations. That means more growth — and more stress — on the detention system than ever.

Folkston is one of 20 ICE facilities that The GEO Group operates across the U.S. Its contract to run the center was part of a 2016 deal between ICE and Charlton County that helped transform a smaller facility run by the company amidst a ramp up of immigration policing under the first Trump administration.

The six-page operating agreement states that The GEO Group would be held to the minimum standards required for “the secure custody, care, and safekeeping of the detainees.”

But the document has few details about what recourse that federal agencies or the county have if the company violates those standards or what penalties it could face.

Federal penitentiaries are run under standards set by the U.S. Department of Justice. In contrast, ICE, which falls under the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, operates facilities under their own guidelines that the agency calls “Performance-Based National Detention Standards.” ICE inspects its facilities annually and documents violations of those standards.

The American Immigration Council, a national group of immigration lawyers, has long criticized ICE for treating its standards as guidance, rather than legally binding rules. Another non-governmental organization, the National Immigration Justice Center, said such criteria, which are open to interpretation and application, create an atmosphere of negligence.

“ICE’s inspection process is deliberately designed to rubber stamp facility compliance with already-compromised standards to keep facilities from closing, no matter the human cost. When oversight bodies do make timely recommendations to phase down facilities, ICE often rejects or ignores them,” the center said in a report in 2023.

GEO started housing detainees in Folkston in 2017. Since then, ICE inspectors have given it poor grades in multiple categories — safety, security, care for detainees, activities and justice. In its oversight reports, ICE refers to violations of its standards as “deficiencies.” Those deficiencies are tallied by category to determine if a facility is in good standing.

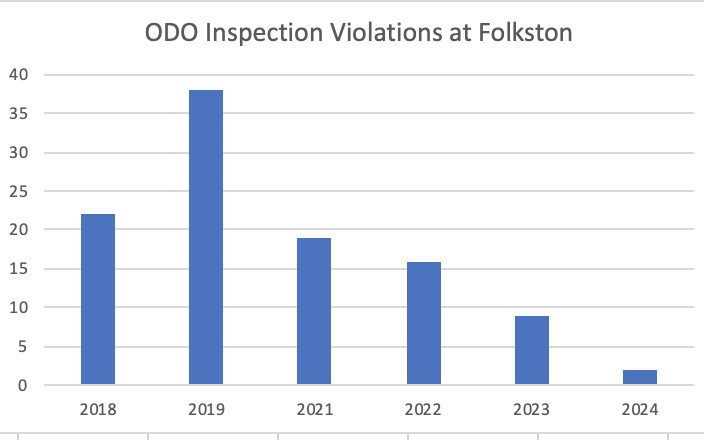

Chart of the ODO Inspection Violations at Folkston.

Folkston received the highest number of violations during the first Trump administration. In 2019, ICE inspectors recorded 38 violations, ranging from poor medical care and food handling to mistreatment of detainees from certain nations.

In that same year, the Department of Homeland Security’s inspector general evaluated ICE facilities, including Folkston, and concluded that the agency “does not adequately hold detention facility contractors accountable for not meeting performance standards.”

ICE reviews at the Folkston showed fewer violations after 2019, but the facility still had problems, according to immigrant rights groups and lawyers.

Those concerns led to a visit to Folkston by investigators from DHS’s inspector general’s office in November 2021. The investigators spent two days at the facility interviewing staff and detainees, and reviewing facility operations and medical records of the foreign nationals.

Their report released to Congress found numerous abuses “that compromised the health, safety, and rights of detainees.”

Their findings confirmed what immigration advocates had alleged. Folkston’s medical staff was not providing “timely access to specialty care or adequate mental health care for detainees, the inspectors’ 48-page report said. It continued:

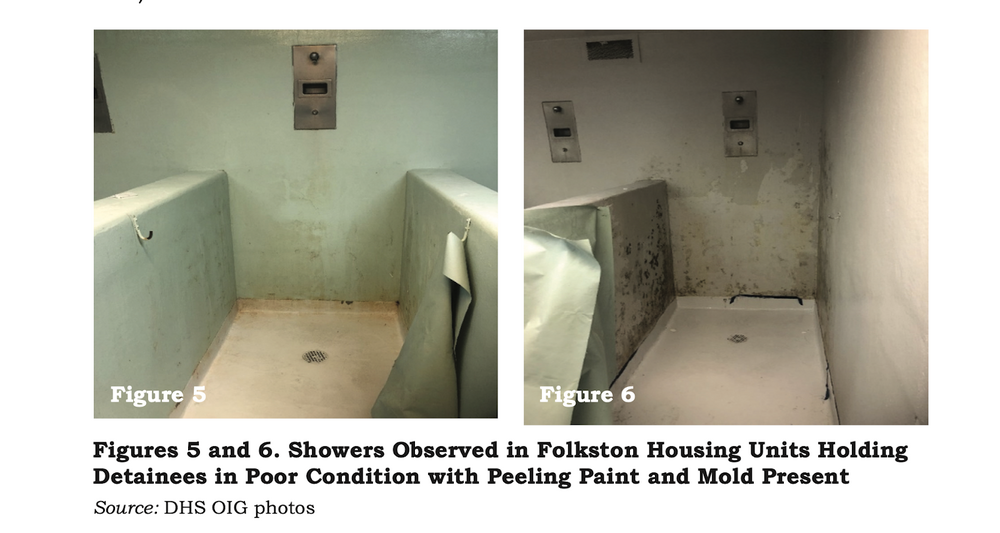

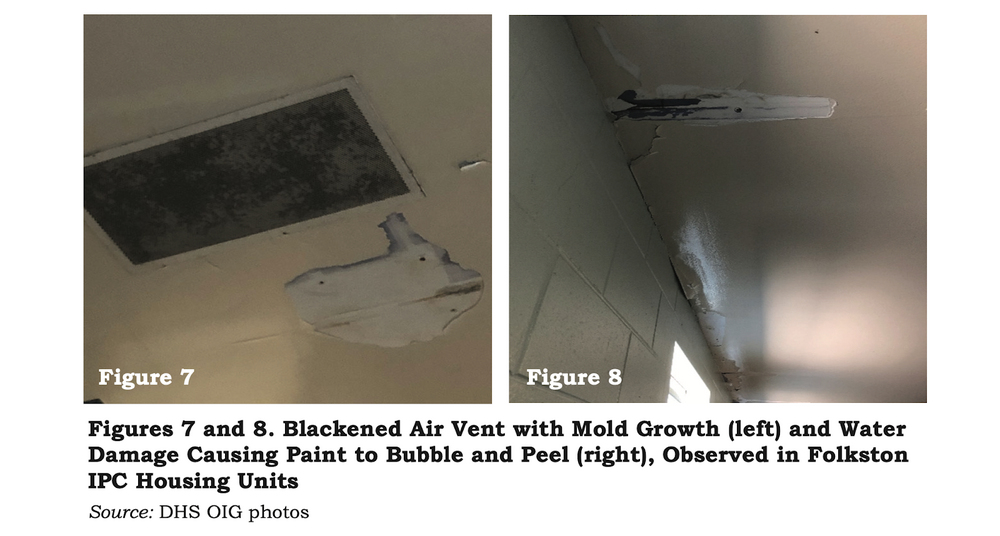

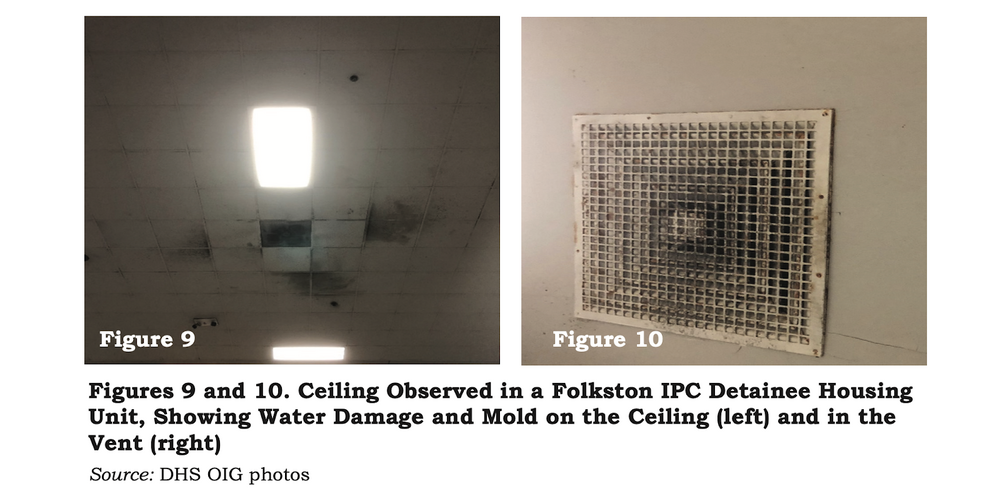

“Folkston facilities were unsanitary and dilapidated, with torn mattresses, water leaks and standing water, mold growth and water damage, rundown showers, mold and debris in the ventilation system, insect infestations, lack of access to hot showers, inoperable toilets.”

Figures 5 and 6. Showers Observed in Folkston Housing Units Holding Detainees in Poor Condition with Peeling Paint and Mold Present.

Figures 7 and 8. Blackened Air Vent with Mold Growth (left) and Water Damage Causing Paint to Bubble and Peel (right), Observed in Folkston IPC Housing Units.

Figures 9 and 10. Ceiling Observed in a Folkston IPC Detainee Housing Unit, Showing Water Damage and Mold on the Ceiling (left) and in the Vent (right).

ICE’s own inspectors, who visited Folkston three months later, gave the facility a “superior” rating.

By 2023, ICE changed its rating system. It received fewer documented violations and was deemed “adequate.”

Civil rights groups differed over those assessments.

The Folkston ICE Processing Center in Folkston, on July 2, 2025.

In 2024 a report by the American Civil Liberties Union about ICE detention centers across the nation concluded that lax operation and safety standards were the norm at facilities such as Folkston and that ICE has failed to enforce federal standards among its private contractors.

”ICE’s oversight process has failed to result in meaningful consequences for detention facilities,” the ACLU report said.

The ACLU report included 63 confirmed deaths of detainees at ICE facilities between 2017 and 2023. One of those was Singh’s death at Folkston.

On June 30, 2023, Singh was arrested in Arizona for unlawfully entering the U.S. and was transferred by ICE from Phoenix to Folkston.

In April of 2024, Singh was placed under medical observation after complaining of chest pain. With no doctor on site, his abnormal electrocardiogram was relayed to an on-call doctor by phone. That physician dismissed the seriousness of the test result and advised staff to schedule a medical appointment for the next day.

An hour later, Singh was found unresponsive.

Staff worked to resuscitate Singh during the half hour it took for the ambulance to arrive. Later, he was declared dead by hospital staff.

In interviews conducted after Singh’s death, a staff member at Folkston said calling 911 was not included in their emergency training. In this case, when a 911 call was finally made, it was routed to the wrong county.

ICE fined contractors in three of the 63 deaths that the ACLU cited in its report. . None of the fines were in response to Singh’s death.

A report prepared by the Government Accountability Office, the U.S. Congress’ official financial watchdog, and released in May 2025 said oversight concerns at Folkston remained. The agency gave several recommendations about how to improve operations there. The GAO report focused on six separate ICE facilities, one of which was Folkston.

A month later GEO announced its contract to expand Folkston.

How medical care will be handled as Folkston mushrooms in size is a concern for immigration advocates.

Daniela Rodriguez, director of Migrant Equity Southeast, another immigrant rights group, said one of the organization’s clients, a detainee from Jamaica, broke his hip while ICE transported him to Folkston. The person has not received treatment for the injury, she said.

“There are people that have a medical emergency that are taken to the hospital, but when they are brought back and they are supposed to continue to have care, they are not getting access to that.”

Members of MESE, who attended several of the public meetings earlier this year where Folkston’s expansion and the contract with The GEO Group was discussed, said members of the Charlton County Commission did not press the company’s representatives for clarity about its operations, in particular how medical emergencies would be handled.

The chairwoman of the Charlton County Commissioners, Alphya Benefield, declined to comment about the negotiations that led to last month’s signing of the $47 million contract with The GEO Group.

Rodriguez had a message for Coastal Georgia Congressman Earl “Buddy” Carter, who took credit for helping broker Folkston’s expansion.

“If it was his family inside of that detention center, we would be advocating for their release. We would be advocating for fair treatment and dignity,” said Rodriguez.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.