Section Branding

Header Content

How Green Can An Interstate Be?

Primary Content

The 16 miles of I-85 from LaGrange, Georgia to the Alabama state line looks pretty ordinary, but the man who it is named for is anything but.

Ray Anderson grew up near this stretch of road, in the town of West Point. He was founder of Interface, the world's leading producer of carpet tiles, but he's probably better known for his environmental epiphany.

"One day, early in this journey, it dawned on me that the way I've been running Interface is the way of the plunderer. Plundering something that's not mine, something that belongs to every creature on Earth," Anderson said in the 2003 documentary, The Corporation.

Anderson pledged his company to something called "Mission Zero." By the year 2020, Interface would make carpet with zero environmental impact.

"When you've got the greenest industrialist of the century named after a dirty highway, he would say 'Go do something good with it'," says Anderson's daughter, Harriet Langford.

(Anderson died of cancer in 2011, at the age of 77).

Langford is also president of the Ray C. Anderson Foundation, which approached The Georgia Conservancy and Ray's alma mater, Georgia Tech, about doing something bigger and bolder -- The Mission Zero Corridor (recently rechristened "The Ray").

"Nobody's just thought how can we make it better? How can it be an energy producer? How can we reduce our carbon?" Langford says.

That job fell into the hands of Richard Dagenhart. He's not a highway engineer, but an architect and professor at Georgia Tech.

Working with current and former students, he set out to find ways to make an interstate weave into its environment. They looked at not just the highway, but all of the land, communities, and ecosystems around it.

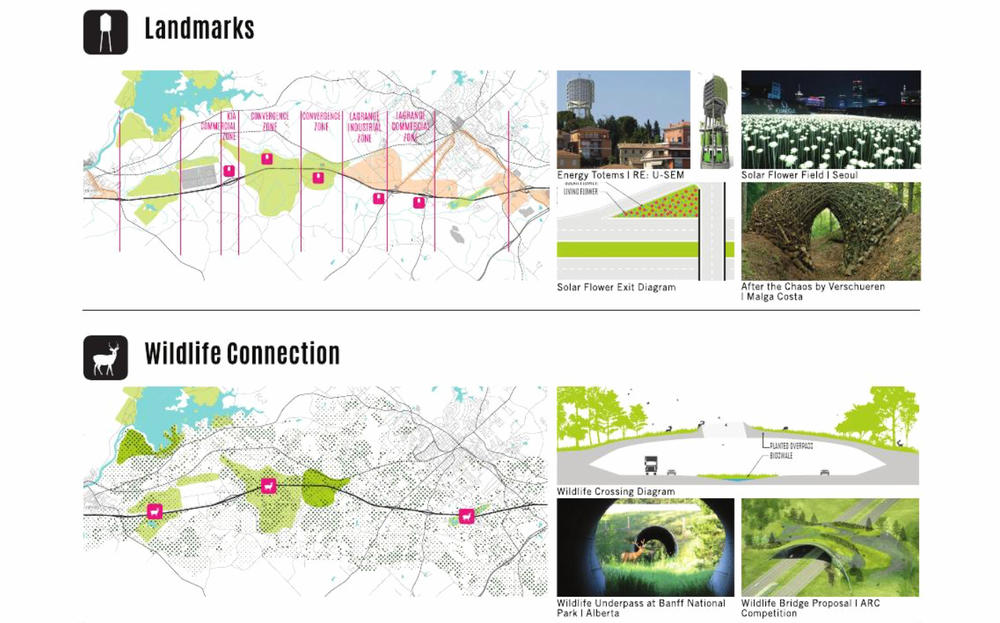

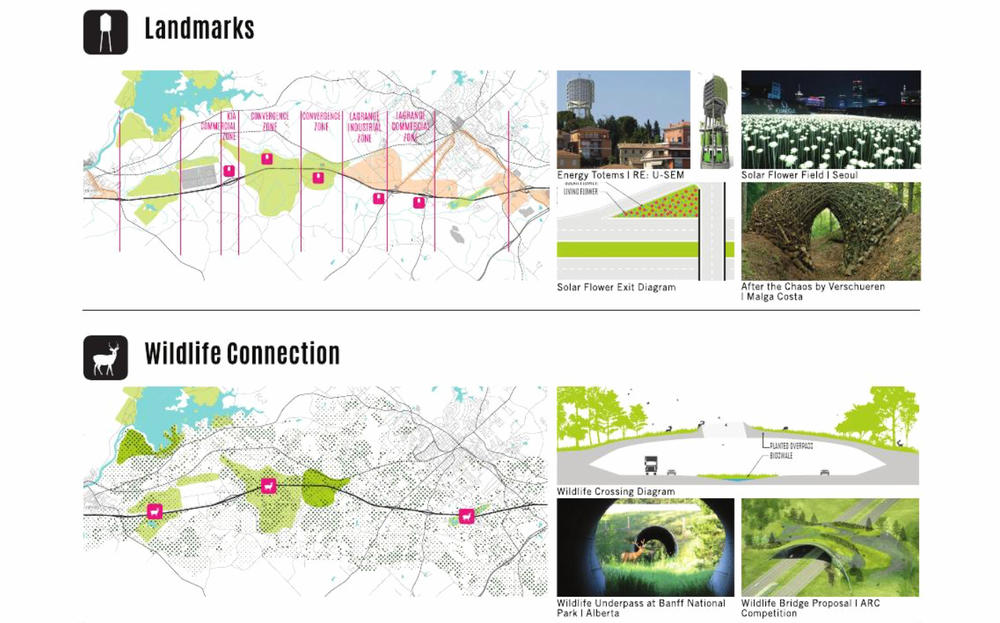

They came up with 103 pages of ideas. Some are pretty wild -- algae farms embedded into overpasses, bridges for wildlife, lighting that adjusts to cycles of the moon. Others are more straightforward -- restoring a creek that runs along the highway and better land use to avoid the sprawl and clutter that's common on interstates. There's one that's already taken root -- a solar powered electric vehicle now stands at the Georgia Welcome Center on the Alabama state line.

But the majority of the corridor remains a concept. A company in the U.K. is sorting through the ideas to determine which are feasible. They'll issue a report by the end of the year. And there's the bigger question: is it even possible to make a highway sustainable?

"It's definitely a substantial effort to retrofit a highway that already exists and put it back into maybe making a lower footprint," says Jeralee Anderson, Executive Director of Greenroads. The Seattle-based group has developed a sustainability ratings system for streets and highways. She says that can have as much to do with cars as the highway itself, with more consumers choosing electric and hybrid models and gas-powered vehicles gain more fuel efficiency.

Funding is an unanswered question, too. Kia Motors, which has an assembly plant on the corridor, funded that electric charging station. The Georgia Department of Transportation has passed a resolution in support of the project, but GDOT hasn't said if they'll help pay for it. Organizers say they're hoping to attract a mix of public, private, and corporate support to make The Mission Zero Corridor a reality.

Harriet Langford, Ray Anderson's daughter, says the project is already changing perceptions.

"We've never looked at a highway," she says. " I've just considered a highway just kinda dumb. It's just there. It serves no purpose except for connection."

She's hoping The Mission Zero Corridor will be less of a connection from A to B, and more of a connection from West Georgia to the future.